Counter-Exposé: The Complex Reality of Founders’ Faith

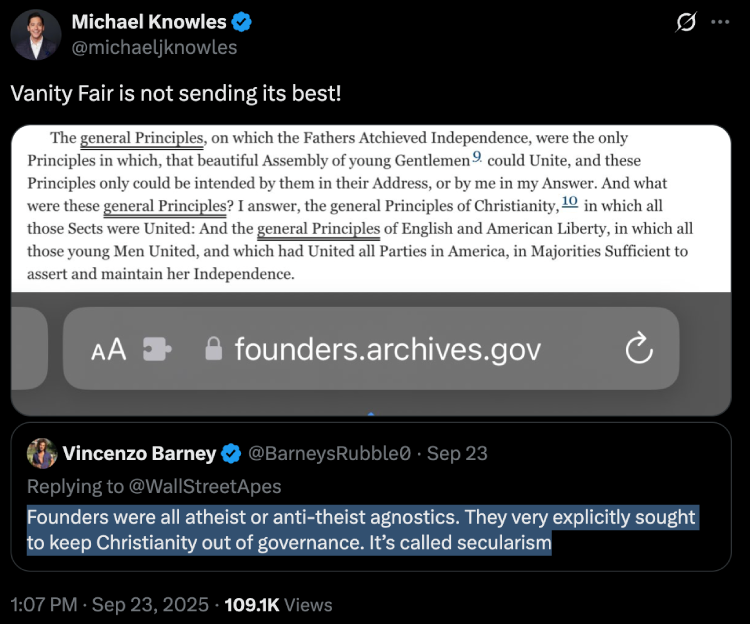

Vincenzo Barney’s sweeping claim fundamentally misrepresents both the diversity of the Founding Fathers’ religious beliefs and their intentions regarding religion in governance.

Vanity Fair is not sending its best! https://t.co/SWzmjO0ugw pic.twitter.com/bUkhSRMdNS

— Michael Knowles (@michaeljknowles) September 23, 2025

The Religious Spectrum Reality

Scholars trained in research universities have generally argued that the majority of the Founders were religious rationalists or Unitarians, not atheists or anti-theists. The religious landscape among key Founders was remarkably diverse:

Orthodox Christians included Patrick Henry, Elias Boudinot, Samuel Adams, and John Jay, who used explicitly Christian language like “Savior,” “Redeemer,” and “Resurrected Christ.” Several Founding Fathers, particularly Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson, notably held deist or deist-influenced beliefs, while others like Washington and Adams occupied a middle ground that scholars describe as “theistic rationalism.”

The Secularism Misunderstanding

The Founders’ approach to religion in governance was nuanced, not driven by anti-Christian animus. They sought to prevent religious establishment—a principle that actually protected religious practice rather than eliminating it. Many Founders, including the deeply religious, supported this separation because they had witnessed how state churches in Europe corrupted both faith and government.

Historical Evidence vs. Modern Mythology

Contemporary colonists understood John Adams, James Wilson, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and George Washington to be orthodox Christians, according to those who knew them personally. The “all atheist” narrative ignores extensive documentary evidence of their religious expressions, church attendance, and integration of providential language into founding documents.

Barney’s claim reflects modern political projection rather than 18th-century reality—a period when outright atheism was both rare and politically untenable.

A Gentle Prescription for Historical Clarity

Perhaps Mr. Barney might benefit from a leisurely afternoon in the American History section of his local library, where he’ll discover that the relationship between faith and founding in early America proves far more intellectually stimulating than Twitter-sized generalizations allow. The nuanced religious landscape of the Founding era—with its deists, Christians, and theistic rationalists navigating questions of conscience, governance, and liberty—offers a complexity that rewards careful study over confident proclamation. One suspects that Madison, Jefferson, and their contemporaries would have appreciated such scholarly diligence before rendering sweeping judgments about their deepest convictions.