Shakers dancing, near Lebanon, New York; engraving by an unknown artist.

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (digital file no. 3a15948)

In the annals of American religious history, few movements have captured the imagination and challenged conventional understanding quite like the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing—better known simply as the Shakers. This remarkable religious community, founded in the industrial mills of eighteenth-century England and transplanted to the fertile soil of Revolutionary America, represents one of the most enduring and fascinating experiments in Christian communalism ever attempted on American soil. Their story is one of divine visions and earthly innovation, of radical equality and austere simplicity, of mystical worship and practical craftsmanship that would influence American culture far beyond their small communities. This group became known colloquially as the “Shakers” and was an offshoot of the Quakers and the French Camisards. Early America provided a welcoming haven for European religious groups and sects yearning for a place to freely practice their distinctive faiths. An earlier example is the Pilgrims, who arrived aboard the Mayflower in 1620, established settlements in what is now New England, and built communities rooted in their unique Puritan beliefs.

The Shaker movement stands as a testament to the power of religious conviction to reshape social norms and create alternative ways of living. For over two centuries, they have maintained their distinctive lifestyle, weathering persecution, social change, and internal challenges while contributing innovations in everything from furniture design to agricultural techniques. Their influence extended well beyond their numerical strength, touching American concepts of gender equality, communal living, pacifism, and spiritual expression in ways that continue to resonate today.

Origins and Beliefs

The genesis of the Shaker movement lies in the spiritual ferment of mid-eighteenth-century England, where traditional religious structures were being challenged by new forms of personal piety and mystical experience. The movement emerged from the intersection of Quaker spirituality, millennial expectation, and the charismatic leadership of a remarkable woman whose visions would ultimately reshape the American religious landscape.

Ann Lee, born around 1736 in Manchester, England, was the daughter of a blacksmith and worked as a mill hand in the burgeoning industrial centers of northern England. Her early life was marked by the harsh realities of working-class existence and the spiritual searching that characterized many in her generation. In 1758, seeking a more emotionally satisfying religious experience than offered by the established Church of England, Lee joined a dissenting group known as the Wardley Society, which had separated from the Quakers under the leadership of Jane and James Wardley.

The Wardley Society practiced a form of worship that incorporated physical manifestations of spiritual experience—shaking, trembling, speaking in tongues, and ecstatic dancing—that gave them the nickname “Shaking Quakers,” eventually shortened to simply “Shakers.” This embodied spirituality, which seemed strange and threatening to conventional religious authorities, became the foundation for what would develop into a complete theological and social system.

Ann Lee’s transformation from follower to leader came through a series of profound personal crises that she interpreted as a divine calling. Her arranged marriage to Abraham Standerin, another blacksmith, proved deeply unhappy, and the deaths of all four of her children in infancy or at birth devastated her emotionally and spiritually. These traumatic experiences coincided with a series of mystical visions that gradually convinced her—and her followers—that she was the recipient of special divine revelation.

National Endowment for the Humanities: Preachers of Peace

“We are the people who turn the world upside down,” said Ann Lee, the young female evangelist who in 1774 brought eight followers from England to establish the Shaker faith in America on the eve of the Revolution. As pacifists and professors of human equality, the Shakers suffered persecution. In 1784, Lee was kidnapped, imprisoned, and beaten so badly that she died within months from a fractured skull. Still the Shakers’ numbers grew. At the religion’s zenith just before the Civil War, there were approximately seven thousand believers living in two dozen communal villages, including one of the smallest and poorest communities, founded in 1794 at Sabbathday Lake, named Chosen Land. Now, it is the only one left.

Central to Lee’s theological vision was the belief that Christ’s Second Coming was not a future event but a present spiritual reality that could be manifested through believers who achieved spiritual perfection. She taught that God existed in both masculine and feminine forms, with Jesus Christ representing the masculine manifestation and herself representing the feminine aspect of the divine. This revolutionary concept challenged fundamental assumptions about gender, divinity, and spiritual authority that would have profound implications for Shaker theology and practice.

The Shaker belief system rested on four fundamental pillars that defined their entire way of life:

Celibacy formed the cornerstone of Shaker practice, based on their understanding that sexual desire and family attachments prevented the complete dedication to God required for spiritual perfection. They viewed celibacy not as a rejection of the goodness of creation, but as a higher spiritual calling that allowed believers to transcend earthly concerns and focus entirely on divine matters. This commitment to celibacy meant that the Shaker community could only grow through conversion, not through natural increase.

Communal ownership reflected their interpretation of the early Christian church described in the Acts of the Apostles, where believers held all things in common. Shakers believed that private property fostered selfishness and inequality, while communal ownership promoted unity and ensured that all members’ needs were met. New members were expected to consecrate all their worldly possessions to the community, though the society maintained provisions for those who later chose to leave.

Confession of sins provided the mechanism for spiritual purification and community accountability. Shakers practiced regular confession to their spiritual leaders, viewing this as essential for maintaining the spiritual purity necessary for their perfected society. This practice also served important community functions, helping to resolve conflicts and maintain the close-knit social bonds essential to communal living.

Separation from the world meant that Shakers maintained their communities as distinct from surrounding society, though they engaged in business relationships and welcomed visitors. This separation protected their alternative lifestyle from outside corruption while allowing them to serve as a beacon of perfected Christian living for the broader world.

GotQuestions.org: Who are the Shakers?

The most influential Shaker leader, Ann Lee, had lost four children as infants and claimed to have received messages from God saying that sex was evil. As a result, abstinence was required in the church as preparation for heaven, where there will be no marriage. Shaker belief was uniquely gender-equal; the wife was subject to her husband, but if she had no husband, she was equal in every way to men (Ann Lee’s husband left her shortly after their arrival in America). This gender-neutrality was also reflected in the Shaker belief that God is both male and female. Jesus was seen as the male manifestation of God and the leader of the first Christian Church. The Holy Spirit is Christ, who is separate from Jesus. Mother Ann Lee was the female manifestation of God, the second coming of Christ, the leader of the second Christian Church, and the Bride of Jesus.

The theological framework that supported these practices drew heavily from millennial Christianity, with Shakers understanding themselves as the advance guard of God’s kingdom on earth. They believed that through their perfected community life, they were hastening the transformation of the entire world into the kingdom of heaven. This sense of divine mission sustained them through persecution and hardship while providing the spiritual energy for their remarkable achievements in community building and craftsmanship.

Departure from traditional Christian doctrine. The Shakers’ theological framework represented a radical departure from orthodox Christian doctrine in several fundamental ways that placed them at the margins of acceptable Christian belief in their era. Most controversially, they rejected the traditional understanding of Christ’s Second Coming as a future eschatological event, instead teaching that Christ had already returned in the person of Ann Lee, whom they regarded as the female manifestation of the divine—a concept that challenged both Christological orthodoxy and conventional gender roles. Their belief in the dual nature of God as both masculine and feminine directly contradicted traditional Trinitarian theology, while their emphasis on continuing revelation through spiritual gifts and prophetic visions undermined the Protestant principle of sola scriptura and the sufficiency of biblical revelation. The Shakers’ requirement of celibacy for all believers stood in stark opposition to mainstream Christianity’s affirmation of marriage as a divine institution, and their practice of confession to human spiritual leaders rather than directly to God echoed Catholic practices that most Protestants had explicitly rejected. Perhaps most significantly, their belief that spiritual perfection could be achieved in this life through communal living and adherence to their principles contradicted the fundamental Christian doctrine of human sinfulness and the necessity of divine grace for salvation, positioning them closer to perfectionist heresies that the church had historically condemned.

Life in a Shaker Community

The daily rhythm of Shaker life reflected their belief that spiritual perfection could be achieved through dedicated work, communal harmony, and ordered living. Every aspect of community life was carefully structured to promote both individual spiritual growth and collective well-being, creating a distinctive culture that balanced spiritual devotion with practical accomplishment. During Mother Ann’s lifetime, the Shaker followers did not construct dedicated buildings for their gatherings. Instead, they lived in ordinary farmhouses and often held worship services outdoors, in open fields or wooded areas. In 1785, just a year after Mother Ann’s passing, James Whittaker—who had journeyed from England with her—and Joseph Meacham, a former Baptist leader from New Lebanon, New York, who had embraced Shaker beliefs, began a deliberate effort to form organized Shaker villages. Their first major undertaking was the construction of a meetinghouse at Mount Lebanon, New York.

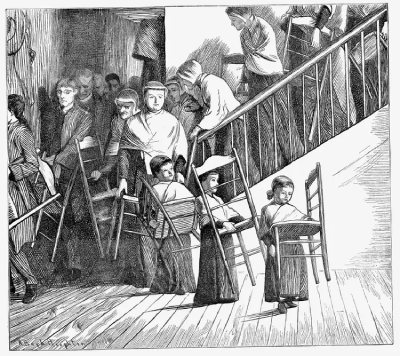

The physical organization of Shaker communities embodied their theological principles in concrete form. The typical Shaker village centered around large, multi-story “family houses” that could accommodate dozens of residents. These buildings were marvels of practical design, featuring separate staircases, hallways, and entrances for men and women to maintain proper separation of the sexes while allowing the community to function as a unified whole. The architecture itself proclaimed Shaker values: functional, beautiful in its simplicity, and designed to facilitate their communal way of life.

Within these family houses, brothers and sisters lived in carefully regulated proximity. Men occupied rooms on one side of the building’s central corridor, women on the other. Multiple individuals shared each room, with single beds arranged with military precision. Privacy was minimal, but the Shakers viewed this arrangement as conducive to spiritual growth and community solidarity. Personal possessions were kept to a minimum, reflecting both their commitment to simplicity and their belief that excessive attachment to material goods hindered spiritual development.

James E. West collectioin, active 1890s c. 1903

The daily schedule began before dawn with the rising bell—five o’clock in summer, half past five in winter. Brothers immediately set about folding their bedclothes with characteristic Shaker precision, laying them neatly across chair backs before departing for morning chores. Sisters likewise attended to their rooms and began their assigned tasks. This early morning routine established the pattern of order and industry that characterized every aspect of Shaker life.

Meals provided opportunities for the community to gather while maintaining their distinctive practices. The dining room accommodated the entire family, with long tables arranged to allow brothers and sisters to sit on opposite sides. Members entered in two files organized by age, with elders and eldresses leading their respective groups. Before and after each meal, the entire assembly knelt in silent prayer, acknowledging their dependence on divine providence for their sustenance.

The commitment to silence during meals reflected the Shaker belief that unnecessary conversation distracted from spiritual contemplation and proper appreciation of God’s gifts. Meals were substantial and well-prepared, but the focus remained on nourishment rather than pleasure. This practice of silent eating, while seeming austere to outsiders, created a sense of communal meditation that reinforced the spiritual dimension of even the most basic activities.

Work assignments reflected the Shaker commitment to gender equality within traditional spheres. Brothers typically handled farming, carpentry, blacksmithing, and other outdoor or heavy labor. Sisters managed cooking, cleaning, textile production, and herb gardening. However, Shaker communities were notably progressive in recognizing and utilizing individual talents regardless of gender, and many sisters developed expertise in areas traditionally considered masculine, while some brothers excelled in domestic arts.

The Shaker approach to work differed fundamentally from the broader American understanding of labor as merely an economic necessity. For Shakers, work was worship—an opportunity to serve God through dedication to excellence and beauty in everything they created. This theological understanding of labor produced the extraordinary craftsmanship for which Shakers became famous, as every piece of furniture, every basket, every tool was created as an offering to divine glory.

Decision-making in Shaker communities operated through a carefully structured hierarchy that balanced spiritual authority with practical governance. Each family was led by elders and eldresses who provided spiritual guidance and oversight of community life. These leaders were chosen for their spiritual maturity and practical wisdom rather than worldly achievement or formal education. The authority structure included provisions for input from community members, though final decisions rested with the leadership.

Economic life in Shaker communities demonstrated their ability to combine spiritual idealism with practical success. Communities typically engaged in multiple enterprises: farming provided basic food security, while specialized crafts and industries generated income through sales to the outside world. Shaker communities became famous for their seed business, furniture making, broom production, and herbal medicines. Their reputation for honesty and quality made Shaker products highly sought after in regional markets.

The integration of work, worship, and community life created a distinctive culture that impressed countless observers. Visitors frequently commented on the cleanliness, order, and prosperity of Shaker villages, as well as the apparent contentment of the inhabitants. This success was not achieved without sacrifice—the demands of communal living required individuals to subordinate personal desires to collective needs—but for many Shakers, the sense of spiritual purpose and community support more than compensated for the limitations of their lifestyle.

The Shaker movement of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shared striking parallels with the countercultural communes established by many 1960s hippies who retreated to places like Oregon’s rural landscapes to create alternative communities. Both groups emerged during periods of intense social upheaval and represented conscious rejections of mainstream society’s materialism, competitive individualism, and conventional religious or spiritual practices. Like the Shakers, many hippie communes embraced communal property ownership, egalitarian decision-making, and alternative approaches to sexuality and family structures—though where Shakers chose celibacy, many hippie communities experimented with free love and non-traditional partnerships. Both movements prioritized simple living, sustainable agriculture, handcrafted goods, and spiritual practices that emphasized direct personal experience over institutional religious authority. The similarities extend to their attraction of young idealists seeking authentic community life, their development of distinctive cultural practices including music and dance, and their eventual struggles with maintaining membership as the broader society’s values shifted and the practical challenges of communal living became apparent. This historical parallel suggests that the human impulse to create intentional communities based on shared values and rejection of dominant cultural norms represents a recurring theme in American social and religious history.

Shaker Dances and Marches

Perhaps no aspect of Shaker life seemed more peculiar to outside observers than their distinctive forms of worship involving rhythmic movement, dancing, and marching. These physical expressions of spiritual devotion, which gave the sect its popular name, represented a radical departure from conventional Protestant worship and embodied the Shakers’ belief that the entire person—body as well as soul—should be engaged in divine praise.

The origins of Shaker dance can be traced to the earliest days of the movement in England, where the Wardley Society’s worship included spontaneous physical manifestations believed to indicate the presence of the Holy Spirit. Ann Lee and her early followers experienced these movements as authentic expressions of divine inspiration, fundamentally different from the staid, cerebral worship they associated with established churches. When transplanted to America, these practices evolved into increasingly elaborate and choreographed forms that became central to Shaker religious identity.

Early Shaker worship was characterized by spontaneous outbursts of physical activity—trembling, shaking, jerking movements, and ecstatic dancing that seemed to reflect the overwhelming presence of divine power. Participants might suddenly begin spinning, leaping, or contorting their bodies in ways that appeared chaotic to observers but felt deeply meaningful to practitioners. These manifestations were understood as evidence that the Holy Spirit was moving directly through believers, bypassing the intellectual and emotional barriers that hindered true spiritual communion.

As Shaker communities matured and grew, their worship practices became more structured while retaining their distinctive physical character. By the early nineteenth century, what had begun as spontaneous spiritual expression had evolved into carefully choreographed dances and marches that incorporated the entire community. These ritualized movements served multiple functions: they maintained the Shaker emphasis on embodied spirituality, provided opportunities for communal participation in worship, and created a sense of unity through synchronized activity.

The most famous of the Shaker dances was the “ring dance,” where community members formed circles and moved in rhythmic patterns while singing spiritual songs. Participants might hold hands, clap, or gesture in unison while rotating around the circle. The ring symbolized eternity and the unity of the community, while the circular movement represented the cyclical nature of spiritual growth and the divine order that governed all creation. These dances could continue for extended periods, creating a trance-like state that participants experienced as profound spiritual communion.

“Marching” represented another distinctive form of Shaker worship, involving the entire community moving in organized processions around the meetinghouse or outdoors. Brothers and sisters maintained their customary separation while participating in these elaborate movements, which might include intricate patterns, sudden changes of direction, and synchronized gestures. The marches often incorporated martial imagery—Shakers saw themselves as soldiers in God’s army—while maintaining their commitment to pacifism through the spiritual rather than physical nature of their warfare.

The “laboring” exercises formed another category of Shaker movement worship, involving repetitive motions believed to promote spiritual purification and divine communion. These might include “shaking” movements designed to cast off sin and worldly attachments, “turning” exercises that symbolized spiritual reorientation, or “bowing” movements that expressed humility before divine authority. Participants often reported profound spiritual experiences during these exercises, describing sensations of lightness, peace, and connection with divine presence.

Musical accompaniment to Shaker dances represented another distinctive aspect of their worship culture. Shaker songs were often received through spiritual inspiration, with community members reporting that they had been given melodies and lyrics directly from the spirit world. These songs combined simple, memorable melodies with texts that emphasized Shaker theology and spiritual experience. Many songs incorporated nonsense syllables or glossolalia, reflecting the Shaker belief that spiritual communication transcended ordinary language.

The integration of dance and music created worship experiences of remarkable intensity and beauty. Observers frequently commented on the grace and synchronization of Shaker movement, noting that what might appear chaotic to outsiders actually followed precise patterns that reflected deep spiritual significance. The combination of visual, auditory, and kinesthetic elements created a total worship experience that engaged participants’ entire beings in ways that conventional Protestant worship could not match.

The decline of elaborate Shaker dance practices paralleled the general moderation of the movement in the later nineteenth century. As communities grew smaller and older, and as the broader American religious culture became more accepting of emotional expression in worship, the distinctive Shaker practices seemed less necessary for maintaining religious identity. Modern Shaker worship retains elements of traditional movement and music, but the elaborate dances and marches that once characterized the faith have largely passed into history as powerful reminders of the movement’s distinctive spiritual vision.

Worship Style

Shaker worship embodied the movement’s core theological commitments while creating a distinctive religious culture that set them apart from all other American denominations. Their approach to communal worship reflected their belief in continuing revelation, the equality of men and women in spiritual matters, and the necessity of engaging the whole person—body, mind, and spirit—in divine service.

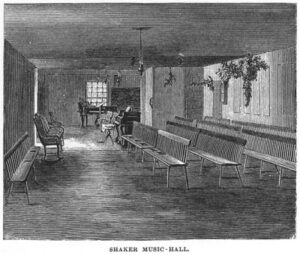

The physical setting for Shaker worship was carefully designed to support their distinctive practices. The meetinghouse, typically the most prominent building in each Shaker village, featured a large, open space with moveable benches that could be quickly rearranged or removed entirely to accommodate dancing and marching. Separate entrances for men and women maintained proper separation of the sexes while allowing the entire community to gather for worship. The interior design emphasized simplicity and functionality, with plain walls, minimal decoration, and excellent acoustics that supported both speaking and singing.

Sunday represented the culmination of the Shaker week, with multiple worship services that brought the entire community together. The principal meeting occurred in the afternoon and might last for several hours, incorporating elements that would seem foreign to most Christian denominations. The absence of ordained clergy meant that worship leadership rotated among community members, with elders and eldresses guiding while encouraging broad participation.

A typical Shaker worship service began with the community gathering in silence, seated on opposite sides of the meetinghouse according to gender. This initial period of quiet preparation allowed participants to center themselves spiritually and prepare their hearts for divine communion. The silence might be broken by spontaneous singing, speaking, or movement as the Spirit moved individual members to participate.

Testimonials formed a central element of Shaker worship, with community members sharing their spiritual experiences, confessing their struggles, and encouraging one another in the faith. These personal revelations created intimacy and accountability within the community while reinforcing key theological themes. Testimonies might include reports of divine visions, descriptions of spiritual progress, or accounts of God’s provision for community needs. The practice reflected the Shaker belief in continuing revelation and the importance of shared spiritual experience.

Singing occupied a place of special importance in Shaker worship, with the community developing a rich tradition of hymnody that expressed their distinctive theology and spiritual experience. Many Shaker songs were believed to be received through divine inspiration, with community members reporting that they had been given melodies and lyrics directly from the spirit world. The songs often featured simple, memorable melodies that could be easily learned and sung without instrumental accompaniment.

The content of Shaker songs reflected their theological emphases: the superiority of celibate life, the importance of separation from worldly corruption, the reality of Christ’s Second Coming through the community, and the joy of perfected Christian living. Many songs incorporated imagery from nature, work, and community life, connecting spiritual themes with daily experience. The famous song “Simple Gifts,” with its emphasis on humility and spiritual transformation, exemplified the Shaker ability to express profound theological concepts in accessible, beautiful language.

Shaker worship also included periods of “laboring,” where the community engaged in synchronized movements believed to promote spiritual purification and divine communion. These exercises might involve shaking movements to cast off sin, turning motions to symbolize spiritual reorientation, or bowing gestures to express humility before divine authority. The physical nature of these exercises reflected the Shaker belief that spiritual development involved the entire person and that bodily discipline was essential for spiritual progress.

The phenomenon of spiritual gifts—supernatural manifestations that occurred during worship—represented another distinctive aspect of Shaker religious practice. Community members might receive divine revelations, speak in tongues, experience healing, or demonstrate other charismatic gifts during worship services. These manifestations were understood as evidence of divine presence and approval of the Shaker way of life, though the community developed careful procedures for evaluating the authenticity of claimed revelations.

Seasonal celebrations added variety and meaning to the Shaker worship calendar. While they generally avoided traditional Christian holidays, which they associated with worldly corruption, Shakers developed their own commemorative occasions that reflected their distinctive history and theology. The anniversary of Ann Lee’s arrival in America, the founding of individual communities, and the spiritual New Year all provided opportunities for special worship services that reinforced community identity and spiritual commitment.

The “Era of Manifestations” (1837-1847) represented the most intense period of Shaker spiritual experience, with worship services becoming elaborate theatrical productions involving multiple simultaneous revelations, complex choreographed dances, and dramatic communications from the spirit world. During this period, community members reported receiving visits from deceased Shakers, biblical figures, and even angels who brought new songs, dances, and spiritual instructions. These supernatural communications often required several hours to enact fully, with participants taking on the roles of various spiritual beings and delivering extended messages to the community.

Modern Shaker worship has retained many traditional elements while adapting to changed circumstances and smaller communities. The remaining Shakers continue to gather for Sunday meetings, incorporating testimonials, singing, and periods of silent worship, though the elaborate dances and manifestations of earlier periods have largely disappeared. Their worship maintains the simplicity, spontaneity, and emphasis on direct spiritual experience that have characterized the movement throughout its history.

Decline and Legacy

The story of Shaker decline represents one of the most poignant chapters in American religious history—the gradual fading of a movement that once seemed destined to transform American Christianity and society. Understanding this decline requires examining both internal factors inherent to Shaker theology and practice and external pressures from a rapidly changing American society that increasingly challenged the movement’s distinctive lifestyle and beliefs.

The seeds of Shaker decline were paradoxically embedded in their greatest strengths. The commitment to celibacy, while providing spiritual focus and community resources, meant that the movement could only grow through conversion rather than natural increase. This fundamental limitation became increasingly problematic as American society offered more attractive alternatives to the Shaker lifestyle. The requirement that members surrender all personal property, while ensuring community economic stability, also created barriers for potential converts who valued individual autonomy and material success.

The peak of Shaker success occurred in the 1840s, when approximately 6,000 believers lived in nineteen communities scattered from Maine to Kentucky. These communities represented remarkable achievements in communal living, combining spiritual devotion with economic prosperity and social innovation. Shaker villages impressed visitors with their order, cleanliness, and apparent harmony, while their products gained national recognition for quality and craftsmanship. The movement seemed positioned to continue growing and influencing American religious and social development.

However, several factors converged during the mid-nineteenth century to challenge Shaker growth and stability. The industrial revolution created new economic opportunities that attracted potential converts away from agricultural communalism. The rise of Spiritualism provided alternative outlets for those interested in supernatural phenomena and communication with the spirit world. The Civil War, despite Shaker pacifism, disrupted their communities and challenged their separation from worldly affairs. Perhaps most significantly, changing attitudes toward sexuality, marriage, and family life made the Shaker lifestyle seem increasingly restrictive and unnatural to potential converts.

The “Era of Manifestations” (1837-1847), while representing the pinnacle of Shaker spiritual intensity, also contributed to the movement’s eventual decline. The elaborate spiritual phenomena and supernatural communications that characterized this period attracted considerable attention but also led to internal conflicts and external skepticism. Some Shakers questioned the authenticity of the manifestations, while outside observers increasingly viewed the community as fanatical rather than inspirational. The eventual moderating of these practices reflected the movement’s recognition that they had become counterproductive for growth and stability.

Economic pressures mounted as Shaker communities struggled to maintain their traditional industries in an increasingly competitive marketplace. The handcrafted goods that had once commanded premium prices faced competition from mass-produced alternatives. Mechanization and industrial development challenged the Shaker commitment to traditional craftsmanship and small-scale production. Some communities attempted to modernize their operations, but this required capital investment and technical expertise that strained their resources and conflicted with their values of simplicity and separation from worldly concerns.

The aging of Shaker communities became increasingly problematic as fewer young converts joined to replace deceased members. By the 1870s, many communities consisted primarily of elderly believers who lacked the energy and vision needed for continued growth and innovation. The burden of caring for aging members stretched community resources while limiting their ability to engage in the missionary activities necessary for attracting new converts. This demographic crisis created a downward spiral that proved increasingly difficult to reverse.

Theological challenges also contributed to the Shaker decline, as American Christianity moved in directions that made Shaker beliefs seem less compelling. The rise of evangelical Protestantism, with its emphasis on personal salvation and individual relationship with Christ, offered spiritual satisfaction without the demanding lifestyle requirements of Shakerism. The development of more liberal Protestant denominations provided outlets for those interested in social reform and gender equality without requiring celibacy and communal living.

Despite these challenges, individual Shaker communities demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability. Some villages survived well into the twentieth century by modifying their practices while maintaining core commitments. The Canterbury, New Hampshire, community remained active until 1992, while the Mount Lebanon community in New York operated until 1947. These later communities often functioned more as retirement homes for aging Shakers than as active religious communities, but they preserved important elements of Shaker culture and tradition.

The legacy of the Shaker movement extends far beyond its numerical strength or institutional survival. Their influence on American craftsmanship, architecture, and design continues to inspire contemporary artisans and architects who value their principles of functional beauty and honest construction. The Shaker aesthetic of simple, elegant forms and natural materials has become synonymous with American design excellence, influencing everything from furniture manufacture to architectural planning.

Social innovations pioneered by the Shakers anticipated many later developments in American society. Their commitment to gender equality, while limited to their own communities, demonstrated the possibility of alternative social arrangements that challenged conventional assumptions about women’s roles and capabilities. Their success with communal property ownership provided a model for later cooperative movements and intentional communities. Their integration of spiritual and economic life offered insights into sustainable community development that remain relevant today.

The Shaker commitment to technological innovation, motivated by their desire to serve God through excellent work, contributed numerous inventions and improvements that benefited the broader society. The circular saw, clothespin, flat broom, and various agricultural implements developed by Shakers reflected their belief that spiritual devotion and practical innovation were complementary rather than contradictory activities. Their willingness to share these innovations without seeking patents demonstrated their commitment to serving human needs rather than pursuing personal profit.

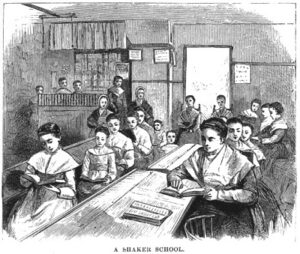

Educational contributions of the Shakers included their progressive approaches to childhood development and learning. Shaker schools emphasized both academic and practical education, preparing children for useful and fulfilling lives, whether they remained in the community or returned to the world. Their recognition of different learning styles and individual talents influenced later developments in progressive education.

The preservation of Shaker villages as museums and historical sites ensures that future generations can learn from their example of successful communal living and spiritual devotion. These preserved communities serve as tangible reminders of an alternative vision of American life that prioritized spiritual values, community cooperation, and sustainable living over individual accumulation and competitive consumption.

How Many Are Left

The current state of the Shaker movement represents both the end of an era and the persistence of a remarkable spiritual tradition that has survived for nearly three centuries. Today, the United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing exists as the smallest active religious community in the United States, yet its story of survival against overwhelming odds continues to fascinate scholars and spiritual seekers who find meaning in their witness to alternative ways of living.

If accepted as a full member, Baxter will join 87-year-old Sister June Carpenter and 68-year-old Brother Arnold Hadd. Hadd entered the community nearly a half century ago and spends his days praying and working on the farm.

As of 2025, only three active Shakers remain, all residing at the Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in New Gloucester, Maine. This tiny community represents the sole surviving remnant of a movement that once numbered in the thousands and operated nineteen active communities across multiple states. The current members—Sister June Carpenter, Brother Arnold Hadd, and the recently arrived Sister April Baxter—embody the continuation of a spiritual tradition that has persevered through centuries of social change and institutional decline.

The recent addition of Sister April Baxter in early 2025 provided a ray of hope for a community that had dwindled to just two members. Baxter, a 59-year-old woman who previously lived in an Episcopal convent, discovered the Shaker community through a visit that she describes as a spiritual calling rather than a conscious decision. Her arrival demonstrates that the Shaker way of life continues to speak to contemporary seekers, even in an age that seems far removed from the nineteenth-century context in which the movement flourished.

Brother Arnold Hadd, who joined the community in 1978 at age 21, represents the bridge between the historical Shaker movement and its contemporary survival. His nearly half-century commitment to Shaker life provides continuity with the community’s past while adapting its practices to modern circumstances. His understanding of Shakerism, focused on what he calls the “three C’s”—confession of sin, community of goods, and celibacy—maintains the theological core that has defined the movement since Ann Lee’s time.

Sister June Carpenter, at 87 years old, serves as the living link to an earlier generation of Shakers who personally knew members from the movement’s more populous days. Her memories and experiences preserve institutional knowledge and spiritual wisdom that might otherwise be lost as the community has shrunk to its current size. Her presence provides stability and continuity for the newer members while maintaining connections to the broader Shaker tradition.

The Sabbathday Lake community has developed innovative approaches to maintaining Shaker traditions while adapting to its extremely small numbers. They continue to observe traditional worship practices, including Sunday meetings that incorporate testimonials, singing, and periods of silent reflection. However, the elaborate dances and marches that once characterized Shaker worship have necessarily been modified for a community of three members, though they preserve the essential spiritual elements that make Shaker worship distinctive.

Economic sustainability for such a small community requires creative solutions that balance Shaker principles with practical necessity. The community maintains traditional activities such as herb growing and food preservation while relying heavily on the support of the “Friends of the Shakers,” an organization founded in 1975 that includes over a thousand members who support Shaker values without fully committing to the celibate communal lifestyle. This broader community of supporters provides both financial resources and volunteer labor that enables the three active Shakers to maintain their village and continue their mission.

The role of non-resident supporters has become crucial for Shaker’s survival in the twenty-first century. These “Friends” participate in seasonal gatherings, assist with maintenance projects, and serve as ambassadors for Shaker values in the broader world. Village director Michael Graham, who first encountered the Shakers as a college student in the 1990s and has worked at the village for decades, exemplifies the dedication of non-resident supporters who find deep meaning in preserving and promoting Shaker heritage.

The question of succession planning presents unique challenges for a community based on celibacy and conversion. With the average age of the current members being relatively high, the community faces the ongoing challenge of attracting new members while maintaining the spiritual and practical standards that have sustained the movement for centuries. The arrival of Sister April Baxter suggests that the Shaker call continues to resonate with some contemporary seekers, but the specific requirements of celibate communal living remain significant barriers for most potential converts.

Modern communication technologies have enabled the small Shaker community to maintain a presence that extends far beyond its physical location. Their website, publications, and occasional media appearances allow them to share their message with a global audience while maintaining their commitment to separation from worldly concerns. This digital presence helps preserve Shaker teachings and traditions while potentially reaching individuals who might be called to join the community.

The preservation of Shaker heritage through museums, historical sites, and academic research ensures that the movement’s contributions to American religious and cultural life will be remembered even if the active community eventually disappears. The Shaker Museum at Mount Lebanon, New York, and numerous other historical sites maintain extensive collections of Shaker artifacts, documents, and buildings that serve educational and scholarly purposes. These preservation efforts complement the witness of the living community while ensuring that future generations can learn from Shaker innovations in spirituality, community life, and craftsmanship.

The contemporary Shakers maintain an attitude of faithful hope regarding their future, trusting in Mother Ann Lee’s prophecy that the movement would eventually “dwindle to as few members as a child could count on one hand, and then overcome all nations.” This millennial expectation sustains their commitment to maintaining their witness regardless of numerical strength, viewing their small size as consistent with biblical teachings about the faithful remnant that preserves divine truth through periods of decline and apparent defeat.

The survival of even three active Shakers represents a remarkable achievement in religious persistence and institutional adaptation. Their continued presence demonstrates that alternative ways of living and spiritual commitment remain possible even in a society that seems increasingly hostile to such choices. Whether the Shaker movement will continue to attract new members or gradually fade into history remains to be seen, but its current witness serves as a powerful reminder of the human capacity for spiritual devotion and community commitment that transcends conventional understanding of success and survival.

As the twenty-first century unfolds, the three remaining Shakers continue their daily routine of worship, work, and witness, maintaining a way of life that has persisted through the Revolutionary War, the Civil War, two World Wars, the Great Depression, and countless social changes that have transformed American life. Their persistence serves as a testament to the enduring power of spiritual conviction and the possibility of living according to principles that transcend worldly measures of success and achievement.

The story of the Shakers continues to fascinate scholars and spiritual seekers alike, offering insights into alternative approaches to religious life, community organization, and spiritual development that remain relevant for contemporary discussions of sustainability, equality, and authentic living. Their small numbers should not obscure their significant contributions to American religious history and their ongoing witness to the possibility of living according to transcendent values in a materialistic age.