Introduction: A Nation Carved in Stone

Beneath the picturesque Alpine villages, chocolate shops, and precision watch factories of Switzerland lies one of the most extensive and sophisticated networks of fortifications ever constructed. For decades, the Swiss Confederation transformed its mountains into a labyrinth of secret bunkers, tunnels, and underground fortresses—a hidden world that embodied the nation’s fierce commitment to armed neutrality and its determination never to be conquered.

This subterranean fortress, much of which remained classified until the end of the Cold War, represents one of the most ambitious defensive projects in modern military history. It is a story of engineering genius, strategic foresight, and a small nation’s refusal to bow to the totalitarian powers that surrounded it during the darkest hours of the twentieth century.

The Genesis: Neutrality Through Strength

Switzerland’s policy of armed neutrality did not emerge from pacifism but from hard-headed pragmatism. Surrounded by great powers throughout its history, the Swiss understood that their independence rested not on treaties alone but on making invasion so costly that even the mightiest armies would think twice.

The modern Swiss bunker system had its origins in the interwar period, but it was the rise of Nazi Germany and the outbreak of World War II that transformed defensive planning from conventional fortifications into something far more radical. When France fell in June 1940 and Switzerland found itself surrounded by Axis powers and their allies, the Swiss military command faced an existential crisis.

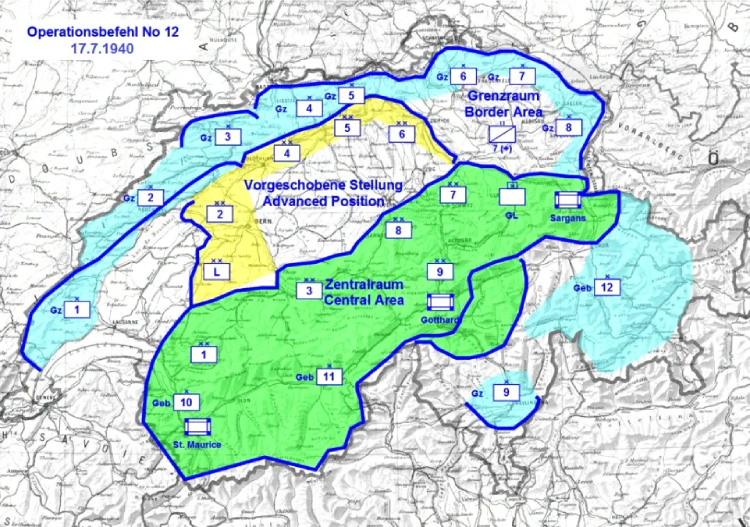

General Henri Guisan, appointed commander-in-chief of the Swiss armed forces, made a momentous decision. Rather than attempting to defend the entire country—an impossibility against the Wehrmacht—Switzerland would implement the “Réduit National” strategy. The heartland of the nation would retreat into an Alpine fortress, a national redoubt from which resistance could continue indefinitely.

The Réduit National: Fortress Switzerland

The Réduit strategy was breathtaking in its scope and audacity. The plan called for concentrating Swiss military forces in the central Alpine region, creating a fortress that could withstand siege while denying the Germans the strategic Alpine passes that connected Germany to Italy. The Swiss would destroy bridges, tunnels, and roads leading into this redoubt, transforming the Alps into an impassable barrier.

At the heart of this strategy lay an extraordinary construction program. Beginning in the late 1930s and accelerating dramatically during the war years, Switzerland embarked on the creation of thousands of fortifications. Artillery positions were carved into mountainsides with such skill that they became virtually invisible. Machine gun nests were hidden behind what appeared to be innocent chalets or barns. Entire mountains were hollowed out to create command centers, hospitals, ammunition depots, and troop barracks.

The ingenuity of Swiss military engineers knew few bounds. In some locations, barn doors and house windows were actually disguised artillery positions. Railroad tunnels contained hidden defensive positions. Even Alpine flowers were sometimes artificial camouflage for observation posts. The message to any potential invader was clear: every mountain, every valley, every seemingly peaceful village might conceal lethal firepower.

Inside the Mountains: Engineering Marvels

The construction of these fortifications represented an engineering achievement that rivaled any in military history. Working often in extreme conditions, Swiss engineers and laborers bored through solid granite to create vast underground complexes. Some bunkers were small, designed for a handful of soldiers; others were underground cities capable of housing hundreds or even thousands of personnel for months.

The largest fortifications featured multiple levels connected by tunnels and elevators. They contained everything necessary for prolonged survival: dormitories, kitchens, infirmaries, command centers, ammunition magazines, and even recreational facilities. Ventilation systems filter air in case of a gas attack. Independent power generation ensured operations could continue even if cut off from the surface. Water sources were secured within the mountains themselves.

Artillery positions represented particular feats of engineering. Massive guns were mounted on rails or turrets deep within the rock, able to emerge, fire, and retreat into the mountain in minutes. Overlapping fields of fire were carefully calculated to create killing zones in the passes and valleys below. Many positions were designed to fire not forward but backward—into Switzerland itself—ready to destroy the infrastructure the Germans would need if they attempted to use Swiss territory for transit.

The St. Gotthard Massif became perhaps the most heavily fortified region, a labyrinth of tunnels and gun positions guarding the critical north-south route through the Alps. Fort Airolo, Fort Motto Bartola, and dozens of other installations turned this strategic crossroads into what military analysts described as potentially the most difficult terrain to assault in the world.

The Psychology of Deterrence

The Swiss bunker system was as much about psychology as military capability. Swiss authorities ensured that Germany’s intelligence services knew about the fortifications—at least in general terms. The message was carefully calibrated: Switzerland could not prevent invasion, but it could make conquest so costly, so prolonged, and so destructive to the Alpine infrastructure that even victory would be defeat.

Hitler’s military planners did indeed study invasion scenarios. Operation Tannenbaum, drawn up in 1940, outlined how German and Italian forces might conquer Switzerland. The plan acknowledged that while conquest was militarily feasible, it would require substantial forces, take considerable time, and result in the destruction of the very infrastructure—particularly the railway tunnels—that made Swiss territory valuable to the Axis war effort.

Switzerland’s strategic value to Germany ultimately lay not in conquest but in cooperation. The Alpine rail tunnels allowed German war materiel to reach Italy. Swiss industry provided precision instruments and other goods. Swiss banks offered financial services. The implicit bargain was that Switzerland maintained these functions while remaining neutral—and Hitler, calculating that the costs of invasion outweighed the benefits, never gave the order.

The bunkers, never tested in combat, had nevertheless served their purpose perfectly.

Cold War Expansion: Nuclear Shadows

If anything, Switzerland’s bunker obsession intensified during the Cold War. The existential threat now came not from invasion but from nuclear warfare. Switzerland launched perhaps the most comprehensive civil defense program in history, determined that the Swiss people would survive even atomic Armageddon.

By law, Switzerland requires nuclear fallout shelters sufficient for its entire population. Every new building had to include a shelter or contribute to a communal facility. Existing buildings were retrofitted. By the 1980s, Switzerland possessed shelter space for over 100 percent of its population—more than any other nation on earth.

These were not token gestures but serious installations. Private home shelters featured thick concrete walls, blast doors, air filtration systems, and supplies for extended habitation. Larger communal shelters, often hidden beneath schools, hospitals, or public buildings, could house thousands. Some were equipped as underground hospitals, complete with operating theaters and intensive care facilities.

The military bunker system underwent similar expansion and modernization. Cold War facilities were designed to withstand nuclear near-misses. Command bunkers were buried deeper and more securely. Communication systems were hardened against electromagnetic pulse. Switzerland’s air force maintained bases with hangar doors carved directly into mountainsides, allowing aircraft to be wheeled into nuclear-proof shelters within minutes of alert.

Perhaps the most extraordinary Cold War facility was the command bunker at Kandersteg, which served as the Swiss military’s primary operations center. Buried deep within a mountain, this installation could coordinate the defense of the nation even during nuclear war, maintaining command and control when surface facilities had been destroyed.

Secrecy and Revelation

For decades, the extent of Switzerland’s bunker network remained classified. Citizens knew shelters existed—they lived above them—but the military installations were state secrets. Topographic maps showed mountains and valleys but omitted the fortifications. Soldiers who served in the bunkers were forbidden from discussing their locations or capabilities.

This secrecy was not merely military prudence but essential to the defensive concept. If an enemy knew the exact location of every installation, they could be targeted. By maintaining ambiguity, Switzerland ensured that any attacker would have to assume that every mountain, every seemingly innocent structure, might hide fortifications.

The end of the Cold War brought revelation. As the Soviet threat receded and Switzerland’s military doctrine evolved, authorities began declassifying information about the bunker system. Former military installations were decommissioned, and some were opened to the public as museums. For the first time, ordinary Swiss citizens and foreign visitors could enter the hidden world that had existed beneath their feet.

These revelations astonished even Switzerland’s own population. The sheer scale of the project—thousands of installations, hundreds of kilometers of tunnels, facilities capable of housing much of the nation’s military and governmental infrastructure underground—exceeded what most had imagined.

Legacy and Transformation

Today, Switzerland’s bunker network stands as both a monument and an anachronism. The nation still maintains civil defense shelters, though with less intensity than during the Cold War. Military bunkers have been largely decommissioned, though some remain operational in modernized form.

Many former bunkers have found new purposes. Some house museums document this unique chapter of Swiss history. Others have been converted into data centers, taking advantage of their security, climate control, and protection from electromagnetic interference. A few have become unusual hotels, offering tourists the chance to sleep in spaces once designed for warfare. Some store Switzerland’s strategic reserves of food, fuel, and medical supplies—a continuation of the preparedness mentality in a different form.

The bunkers also serve as vast storage facilities for Swiss archives and cultural treasures. Deep beneath the mountains, protected from fire, flood, and disaster, rest precious documents and artifacts that constitute the nation’s historical memory.

Conclusion: The Philosophy in Stone

Switzerland’s secret bunkers represent more than military installations. They embody a national philosophy: that freedom and independence must be actively defended, that deterrence requires credible capability, and that survival demands preparation for worst-case scenarios most prefer not to imagine.

The bunkers were never merely about defeating invaders but about preserving Swiss civilization itself—the democratic institutions, cultural identity, and way of life that define the nation. In hollowing out mountains and preparing for siege, the Swiss declared that their independence was not negotiable, that they would endure any hardship rather than submit to foreign domination.

History vindicated this approach. Switzerland emerged from World War II with its neutrality and independence intact—one of the few European nations that could make such a claim. The Cold War passed without the nuclear catastrophe that seemed, at times, terrifyingly possible. The bunkers were never needed for their intended purpose, but in never being needed, they succeeded completely.

Today, visitors walking through decommissioned bunkers encounter vast empty spaces carved from living rock, silent artillery positions that never fired in anger, and corridors that echo with absence. Yet these spaces are not empty of meaning. They stand as testament to the power of deterrence, the value of preparedness, and the lengths to which free people will go to remain free.

In the end, Switzerland’s secret bunkers tell a story that transcends military history. They remind us that the greatest fortifications are not merely physical but psychological, that the most successful defensive strategy is one that prevents war rather than wins it, and that a small nation, properly prepared and utterly determined, need not fear the giants that surround it.

The mountains of Switzerland keep their secrets still, but the secrets they reveal speak to something fundamental about the human capacity for resilience, ingenuity, and the stubborn refusal to surrender in the face of overwhelming odds. In stone and steel and the darkness beneath the Alps, the Swiss carved not merely bunkers but a monument to the price of freedom and the determination to pay it.