Detailed Summary of “Carthage Conspiracy”

by Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill

“Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith” by Dallin H. Oaks and Marvin S. Hill exemplifies a hallmark of modern Mormon apologetics, where rigorous legal and historical analysis serves as a veneer for reframing inconvenient facts—such as Joseph Smith’s provocative destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor, declaration of martial law, and mobilization of the Nauvoo Legion—within a faithful narrative of victimhood and political persecution.

Despite its secular publication and scholarly acclaim, the book’s central thesis of a “deliberate political assassination” by Hancock County elites subtly preserves the martyrological essence of traditional LDS accounts by shifting emphasis from spontaneous frontier backlash to calculated Gentile conspiracy, thereby minimizing Smith’s agency in escalating the Nauvoo conflicts.

This approach mirrors contemporary apologists affiliated with institutions like FAIR or the Neal A. Maxwell Institute, who deploy sophisticated source criticism and philosophical framing—drawing on Thoreau, Calhoun, and others—to interpret primary evidence through a pre-existing belief system that privileges Mormon exceptionalism and portrays the church as an aggrieved force for higher law amid democratic failures. Oaks’s later ascent to LDS apostle and Utah Supreme Court justice further underscores how such works integrate academic objectivity with confessional loyalty, whitewashing the theocratic brinkmanship of early Mormonism as mere religious persecution.

Make no mistake: for a religion that elevates Joseph Smith to a status second only to Jesus Christ—portraying him as a modern prophet whose revelations birthed a restored gospel—its leaders, apologists, and adherents spare no evidentiary effort, contrived or otherwise, to buttress that exalted view. This imperative manifests in works like “Carthage Conspiracy,” where Oaks and Hill meticulously dissect trial transcripts and legal doctrines not merely to illuminate history, but to recast Smith’s fatal provocations—such as razing the Nauvoo Expositor press under color of municipal authority and summoning the Nauvoo Legion amid cries of martial law—as mere symptoms of Gentile intolerance rather than escalatory theocratic overreach. Contemporary parallels abound in outlets like FAIR Mormon or the Interpreter Foundation, which deploy nuanced source criticism, probabilistic modeling of witness testimonies, and appeals to “higher law” philosophy to sanitize doctrinal polygamy scandals, Book of Mormon anachronisms, or Smith’s multiple conflicting First Vision accounts, all while framing critics as conspiratorial antagonists. Such tactics ensure that even damning primary evidence, from affidavits of Nauvoo dissenters to non-Mormon depositions on bloc voting intimidation, is subordinated to a faithful metanarrative of perpetual persecution and divine vindication.

Here is the description of Joseph Smith’s work written by then Elder John Taylor in the obituary that he wrote after the “Martyrdom” and which is currently recorded as Doctrine and Covenants 135:3. It reads:

Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer of the Lord, has done more, save Jesus only, for the salvation of men in this world, than any other man that ever lived in it. In the short space of twenty years, he has brought forth the Book of Mormon, which he translated by the gift and power of God, and has been the means of publishing it on two continents; has sent the fulness of the everlasting gospel, which it contained, to the four quarters of the earth; has brought forth the revelations and commandments which compose this book of Doctrine and Covenants, and many other wise documents and instructions for the benefit of the children of men; gathered many thousands of the Latter-day Saints, founded a great city, and left a fame and name that cannot be slain. He lived great, and he died great in the eyes of God and his people; and like most of the Lord’s anointed in ancient times, has sealed his mission and his works with his own blood; and so has his brother Hyrum. In life they were not divided, and in death they were not separated!

“Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the

Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith”

Publication & Reception

Publication & Reception

Published in 1975 by the University of Illinois Press, “Carthage Conspiracy: The Trial of the Accused Assassins of Joseph Smith” won the Mormon History Association Award for Best Book of the Year in 1976. The work emerged from research the authors began during their student days at the University of Chicago, where they discovered extensive original documents in the Carthage, Illinois, courthouse.

Central Thesis

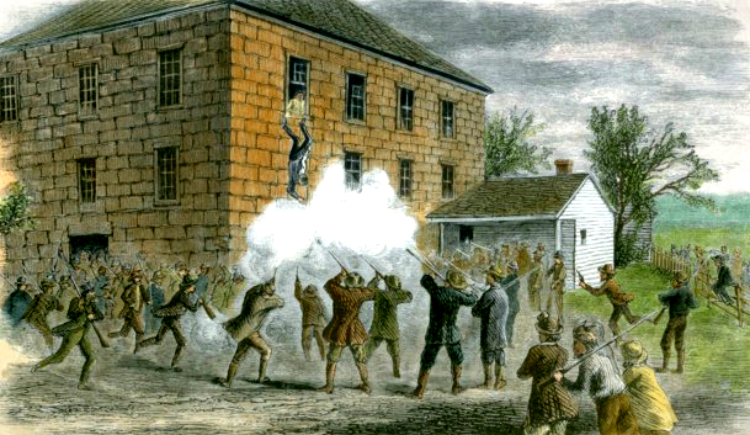

The book’s fundamental argument is that the murders of Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum at Carthage jail on June 27, 1844, were not spontaneous acts of mob violence but rather a deliberate political assassination committed or condoned by prominent citizens of Hancock County, Illinois. This reframes the traditional Mormon narrative of martyrdom as a calculated political murder designed to resolve the growing tensions between Mormon and non-Mormon populations in the region.

Historical Context

The book situates the murders and subsequent trial within the broader framework of Mormon-non-Mormon conflict in 1840s Illinois. The growing Mormon population in Nauvoo had created significant political, economic, and social tensions with surrounding communities. The immediate trigger for the violence was Joseph Smith’s destruction of the Nauvoo Expositor, an anti-Mormon newspaper, which led to charges against him and his imprisonment in Carthage jail.

The Murder and Defendants

Five men were indicted for the murders: Thomas C. Sharp, William N. Grover, Jacob C. Davis, and two others. The trial took place in May 1845, nearly a year after the murders, in the same Carthage courthouse. The defendants were all acquitted despite evidence suggesting a broader conspiracy involving leading citizens of the county.

Legal Analysis

One of the book’s major contributions is its sophisticated legal analysis. The authors examine the prosecution’s strategy, which relied on proving conspiracy since only establishing who pulled the trigger would not implicate the broader network of perpetrators. The prosecution faced enormous challenges: unfriendly witnesses, a hostile environment, and remarkably, the refusal of Mormon Church leaders to cooperate. Even Apostle John Taylor, who was present during the murders and was himself wounded, actively avoided being subpoenaed, going to great lengths not to testify. This Mormon reluctance to participate stemmed from a desire to maintain peace and avoid further conflict.

Throughout the narrative, Oaks (who would later become a Utah Supreme Court justice and LDS apostle) provides expert legal commentary, analyzing the attorneys’ arguments, explaining relevant law, and critiquing the legal strategies employed by both sides.

Philosophical Framework

A central intellectual contribution of the book involves exploring profound questions about authority and justice in a democratic society. The authors examine the tension between the rule of law and popular sovereignty, asking: What is the ultimate source of authority in a democracy? Should citizens recognize a “higher law” above statutory law? Can juries legitimately excuse crimes through appeal to popular approval or community sentiment?

These philosophical questions are addressed primarily in the introduction and concluding chapter, drawing on thinkers including Henry David Thoreau, John C. Calhoun, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, and Roscoe Pound. However, the trial participants themselves provide compelling practical answers to these theoretical questions throughout the proceedings.

Trial Proceedings

The book provides extensive detail on the trial itself, including:

- The selection of the jury, which proved extremely difficult given the political tensions

- The testimony of witnesses, many of whom appeared to know more than they revealed

- The prosecution’s struggle to prove conspiracy in an environment where community sympathy lay with the defendants

- The defense strategy of creating a reasonable doubt

- The ultimate acquittal of all defendants

The authors note that the trial took place during “court week” in Carthage, when these circuit court proceedings served as major social and entertainment events for the frontier community, drawing crowds comparable to theater or opera in more established areas.

Chapter Structure

Based on the table of contents, the book’s chapters include:

- “Court Week in Carthage” – Setting the scene

- “Murder…by a Respectable Set of Men” – The assassination itself

- “To Vindicate the…Broken Pledge of the State” – The state’s responsibility

- “Elections and Indictments” – Political context

- “To Secure Pre-Trial Advantage” – Legal maneuvering

- “The Courtroom and the Contestants” – The participants

- “A Jury of ‘Intelligence, Probity and Worth'” – Jury selection

- “Quiet Perjury to Screen a Murder” – Witness testimony issues

- “Suppositions Ought not to Hang Anyone” – Defense arguments

- “To ‘Tranquilize the Public Mind'” – The verdict’s impact

- “Away to a Land of Peace” – Mormon exodus aftermath

- “The People Reign in the American Political World” – Democratic theory conclusions

Historical Significance

The book places the murders and trial in the broader context of both Mormon and American legal history. It examines how politically motivated crimes are handled when they enjoy popular support, and what happens when the justice system must function in an environment of deep community division. The trial’s outcome effectively demonstrated that when crimes have broad community backing, securing convictions becomes nearly impossible, even with clear evidence of guilt.

Scholarly Approach

The authors aimed to produce a work valuable to both scholars and general readers, balancing rigorous historical analysis with compelling narrative. They deliberately avoided what they call the “traditional, legendary approach” to Joseph Smith’s martyrdom, instead treating it as a serious historical and legal event requiring objective analysis.

The book draws on extensive primary sources, including original court documents, contemporary newspaper accounts, personal correspondence, and Church archives, providing a thoroughly documented examination of this pivotal moment in American religious history.

Legacy

“Carthage Conspiracy” has been recognized as a landmark work in Mormon historiography and American legal history, praised for its analytical rigor, narrative quality, and willingness to examine uncomfortable questions about justice, mob violence, and religious persecution in nineteenth-century America.

Mormons Spin the Facts About Joseph Smith’s Demise

Framing the Narrative as Political Assassination

The summary presents the book’s “fundamental argument” as a reframing of Joseph and Hyrum Smith’s deaths from spontaneous mob violence into a “deliberate political assassination” by or with the blessing of Hancock County elites, purportedly to resolve rising tensions between Mormons and non‑Mormons. This framing elides the extent to which Joseph Smith himself had already departed the realm of ordinary legal subject and stepped into open defiance of state authority by destroying the Nauvoo Expositor, declaring martial law, and mobilizing the Nauvoo Legion, conduct that contemporaries—Mormon and non‑Mormon—understood as at least quasi‑rebellious. By casting the killing predominantly as “assassination” rather than as frontier vengeance in the wake of perceived lawlessness, the summary adopts a vocabulary that suggests a largely passive, victimized Mormon community and a wholly predatory Gentile establishment, minimizing the degree of agency, provocation, and brinkmanship exercised by Smith in the months before Carthage.

The claim that this “reframes the traditional Mormon narrative of martyrdom as a calculated political murder” also quietly preserves the church’s preferred martyrological lens. “Political assassination” imports a modern, morally freighted category that implies illegitimate elimination of a legitimate political actor, while sidestepping the question whether Smith’s fusion of ecclesiastical and civil authority—especially in Nauvoo’s city court, charter, and militia—had itself become incompatible with republican legal order as Illinoisan elites understood it. The summary thus adopts on its face a corrective posture toward “legend,” but in substance it replaces one theologically useful narrative (martyrdom) with another equally useful one (political assassination) that continues to center Mormon victimhood and downplays the reciprocal cycle of intimidation and violence in the region.

Legal Analysis and the Problem of Selective Emphasis

The summary lauds the book’s “sophisticated legal analysis,” particularly its focus on conspiracy as the linchpin needed to link the five indicted defendants to the killings. That analytic premise is sound as a matter of nineteenth‑century doctrine: without proof of a prior agreement or common design, only those who actually fired shots through the jail window or stormed the stairs could be convicted as principals. Yet the summary’s account borders on apologetic when it explains the prosecution’s failure mainly by reference to “unfriendly witnesses,” a “hostile environment,” and above all the “refusal of Mormon Church leaders to cooperate,” including John Taylor’s deliberate evasion of process. The net effect is to cast Mormons as tragically high‑minded—seeking “peace” and “avoid[ing] further conflict”—rather than as political actors who made a calculated decision to delegitimize a state legal proceeding they regarded as stacked and whose outcome they had already discounted.

A more candid legal critique would foreground three hard realities that the summary soft‑pedals. First, the case was structurally weak because, even by the authors’ own admission, those most centrally involved in the planning and execution of the attack were never in the dock, making any conspiracy theory hinge on layers of inference. Second, Judge Young’s jury‑panel decisions and the make‑up of the venire reflected a broader political accommodation: neither side had confidence the legal system could produce a verdict that both would respect, and the court ultimately presided over a performance of legality rather than a genuine contest of proof. Third, Mormon non‑cooperation was not simply principled pacifism; it was also a strategic withdrawal from a forum they had already deemed illegitimate, consistent with a well‑documented pattern of appealing to “higher law” when positive law was unfavorable and invoking state protection when it suited them. By emphasizing hostile circumstances but not reciprocal manipulation of legal process, the summary tilts the analysis toward a story of heroic but thwarted legality rather than of mutual instrumentalization of the courts.

Philosophical “Higher Law” and Mormon Exceptionalism

The summary praises the book’s philosophical exploration of “authority and justice in a democratic society,” asking whether citizens may appeal to a “higher law” and whether juries may excuse crimes via community sentiment. That framing describes with some accuracy antebellum debates over nullification, popular sovereignty, and civil disobedience, but the summary treats Mormon recourse to “higher law” primarily as a question posed to non‑Mormon actors—jurors, county elites, and state officials—rather than as a mirror held up to Mormon behavior. In doing so, it underplays the central irony that Nauvoo’s leadership repeatedly asserted a functional higher‑law prerogative: overriding territorial press freedom with the destruction of the Expositor, using municipal courts to short‑circuit external arrest warrants, and deploying the Nauvoo Legion as a quasi‑sovereign armed force.

The summary also signals that the introduction and conclusion draw on Thoreau, Calhoun, Lincoln, Jefferson, and Roscoe Pound to interrogate these questions, a canon that encodes a particular liberal‑legalist reading of American political development. Yet that intellectual frame risks dignifying what is, at base, a localized conflict over power, land, and votes by elevating it to a referendum on abstract “popular sovereignty,” thereby further centering Mormon experience as the occasion for a meditation on American constitutionalism. A truly critical analysis would ask not merely whether anti‑Mormon jurors illicitly invoked “higher law” to acquit the defendants, but also whether the Nauvoo theocracy itself represented a rejection of the very constitutional order that Oaks and Hill retrospectively celebrate. The summary’s silence on that symmetrical question illustrates how Mormon‑inflected scholarship can universalize one side’s anxieties into “philosophical questions” while relegating the other’s to “mob” sentiment.

Objectivity, Sources, and Mormon Historiographical Control

The summary characterizes the work as a deliberate move away from “traditional, legendary” Mormon depictions of Joseph Smith’s “martyrdom,” claiming that the authors “treat it as a serious historical and legal event requiring objective analysis.” On one level, this is descriptively accurate: the book’s publication by a secular academic press, its reception by legal historians, and its use of primary sources marked a distinct departure from devotional narratives. But the summary’s insistence on objectivity obscures the structural asymmetry in source access and interpretive framing that attends Mormon archival control. Oaks and Hill write from within a tradition in which church archives, correspondence, and internal records are curated by the institution whose founding figure is under examination, and that institution retains decisive control over what is made available and how it may be contextualized.

Moreover, the summary touts the use of “extensive primary sources” including court documents, newspapers, correspondence, and church records as if source abundance equated to neutrality. Yet the selection and weighting of those materials are themselves interpretive acts, influenced by Oaks’s later roles as Utah Supreme Court justice and LDS apostle and Hill’s career within BYU’s institutional orbit. The summary nowhere confronts the possibility that this positionality encourages a narrative that is tough‑minded about trial mechanics and local non‑Mormon actors but circumspect about the deeper structural and doctrinal roots of the conflict in early Mormon claims to exclusive authority, prophetic infallibility, and theocratic governance. Thus, even as the book is celebrated as a “landmark work” in Mormon historiography, the summary presents its perspective as if it were simply professional history, not also an instance of confessional self‑representation under the guise of legal realism.

Justice, Acquittal, and the Uses of Martyrdom

Finally, the summary concludes that the trial “effectively demonstrated that when crimes have broad community backing, securing convictions becomes nearly impossible, even with clear evidence of guilt” and that the book is “praised for its analytical rigor” and willingness to examine “uncomfortable questions about justice, mob violence, and religious persecution.” That claim bypasses two critical issues. First, the “clear evidence of guilt” formulation presupposes precisely what was at issue: who, among which class of actors, bears legal as opposed to moral responsibility for the Carthage attack, and how far liability extends up the chain of political influence. By positing a broad but diffuse conspiracy among “respectable” citizens and then treating the defendants’ acquittal as proof of collective lawlessness, the narrative both condemns non‑Mormon Illinois as a failed rule‑of‑law project and reinforces Mormon self‑understanding as a people repeatedly betrayed by American institutions.

Second, the emphasis on “religious persecution” in the summary allows the book’s legal history to be reabsorbed into a sacralized story of martyrdom that it ostensibly set out to demythologize. The same conflict can be read, with at least as much plausibility, as the violent collision between an aggressively expansionist, theocratic movement and neighboring communities anxious about bloc voting, economic domination, and theocratic courts, in a legal environment ill‑equipped to manage quasi‑sovereign religious polities inside a state. By choosing to foreground persecution and political assassination rather than mutual radicalization and structural incompatibility, the summary reflects how Mormon scholarship can “spin” the Carthage episode into a morality tale in which Joseph Smith’s demise confirms rather than problematizes the Latter‑day Saint claim to be the aggrieved guardian of true law in nineteenth‑century America.

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_of_Joseph_Smith

- https://blogs.bu.edu/guidedhistory/historians-craft/mormon-conflict-and-controversy-at-nauvoo-1839-1846/

- https://ppl-ai-file-upload.s3.amazonaws.com/web/direct-files/attachments/27486319/21ce861e-0e0f-4104-a551-60441962f1fa/Summary-of-Carthage-Conspiracy.txt

- https://www.dialoguejournal.com/articles/the-law-above-the-law-carthage-conspiracy-the-trial-of-the-accused-assassins-of-joseph-smith/

- https://famous-trials.com/carthrage

- https://famous-trials.com/carthrage/1254-chronology

- https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/introduction-to-state-of-illinois-v-williams-et-al-and-state-of-illinois-v-elliott-c/1

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killing_of_Joseph_Smith

- https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/?id=p007620

- https://ndlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Scharffs-Cropped-1.pdf

- https://doctrineandcovenantscentral.org/historical-context/dc-135/

- https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/articles/road-to-carthage-podcast-episode-8-transcript

- https://byustudies.byu.edu/article/carthage-conspiracy-the-trial-of-the-accused-assassins-of-joseph-smith

- https://www.thechurchnews.com/2020/3/18/23216013/joseph-smith-president-oaks-church-history-symposium/

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/church-history/article/abs/carthage-conspiracy-the-trial-of-the-accused-assassins-of-joseph-smith-by-dalin-h-oaks-and-marvin-s-hill-urbana-university-of-illinois-press-1975-xiv-249-pp-795/F569725FFF01A76AAB0675BABC44E8E0

- https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1060&context=lawreview

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt1bkm513

- https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1813&context=byusq

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zEfxyRTnzh0

- https://www.nps.gov/places/carthage-jail.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carthage_Conspiracy

Johnny Harris is an Emmy-winning American journalist, filmmaker, and YouTuber based in Washington, D.C., known for blending motion graphics with cinematic storytelling to explain global issues.

Raised in a Mormon family in Oregon, Harris attended Brigham Young University for a BA in international relations before earning an MA in global peace and conflict resolution from American University. He later left the LDS Church, documenting his journey in videos like “Why I Left the Mormon Church.”

Johnny Harris recounts Mormonism’s origins from Joseph Smith’s 1844 murder in Illinois, leading to Brigham Young’s exodus to Utah Territory (then Mexican land), where pioneers built a theocratic “Zion” with grid cities, temples, a Deseret economy, currency, and alphabet amid apocalyptic expectations. He highlights their failed bid for the massive State of Deseret, federal tolerance for their industriousness despite polygamy—publicly endorsed by Young in 1852 as divine for exaltation (godhood), involving his 56 wives and child brides—and land theft from Utes.

Conclusions on Mormonism

Harris reflects personally, raised in this “sugar-coated” pioneer narrative of persecution and sacrifice that shaped his identity, yet now sees it tied to “exploitation” of women/children, Native dispossession, male-centric divine commands, and end-times zealotry justifying chosen-people supremacy. He grapples with finding past “meaning and beauty” in what he deems profoundly “wrong” and “damaging.”