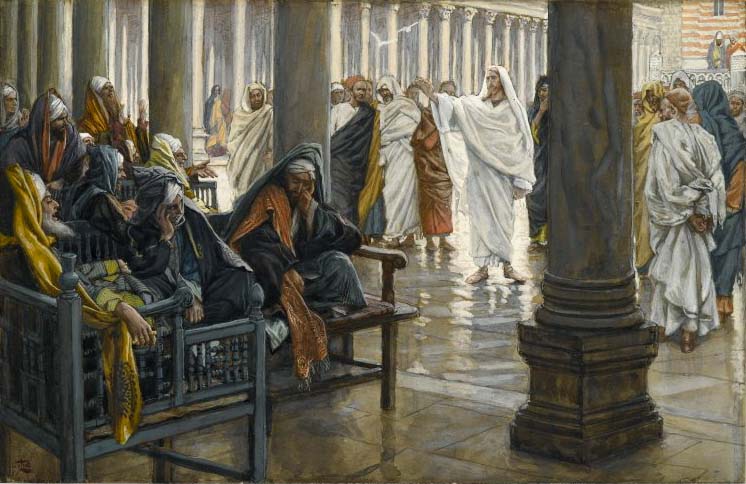

Photo: James Tissot, Woe unto You, Scribes and Pharisees, Brooklyn Museum.

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published

(or registered with the U.S. Copyright Office) before January 1, 1931.

Whitewashed Tombs:

Matthew 23 and the Structural Parallels Between Pharisaic Judaism

and Latter-day Saint Religious Culture

A Theological and Historical Analysis

Introduction: The Enduring Relevance of Jesus’ Prophetic Critique

In the twenty-third chapter of Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus delivers what stands as perhaps His most sustained and devastating critique of religious leadership recorded in Scripture. The seven woes pronounced against the scribes and Pharisees constitute not merely a first-century polemic but an enduring prophetic template by which all religious systems claiming divine authority may be evaluated. This passage has echoed through centuries of Christian thought, serving as a warning against the institutionalization of faith into systems that prioritize external conformity over internal transformation.

The thesis that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints exhibits structural and cultural parallels to the very Pharisaic system Jesus condemned deserves serious scholarly examination. From its founding in 1830, Joseph Smith crafted a religious movement that retained sufficient traditional Christian vocabulary to maintain a veneer of orthodoxy while introducing theological innovations that represented radical departures from biblical Christianity.

The religious errors embedded in Mormonism’s foundation have compounded over nearly two centuries, amplified by a plethora of writers who pen theological fantasies spun from imagination rather than derived from careful exegesis of the biblical text. General authorities, apologists, and church educators have constructed elaborate doctrinal edifices built not upon the rock of Scripture but upon the shifting sands of continuing revelation, philosophical speculation, and institutional necessity. Each generation adds new obtuse layers of interpretation and expectation, further obscuring the simple gospel while creating an ever-more-complex labyrinth of requirements for the faithful to navigate.

The following is a perfect example of LDS leadership making it up as they go.

LDS President Gordon B. Hinckley, 15th President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints:

“There is no limit to your potential. If you will take control of your lives, the future is filled with opportunity and gladness. You cannot afford to waste your talents or your time. Great opportunities lie ahead of you.”

Now I offer you a very simple recipe which, if observed, will assure your happiness. It is a simple four-point program. It is as follows: (1) pray, (2) study, (3) pay your tithing, and (4) attend your meetings.

The statement above represents a fundamental misunderstanding of Christian soteriology and sanctification. While superficially encouraging, it subtly replaces the gospel of grace with a prosperity-tinged works righteousness that Scripture consistently rejects. Our previous post breaks this down.

As the movement matured, Smith’s innovations crystallized into an elaborate system of laws, ordinances, and cultural expectations that bear striking resemblance to the “heavy burdens” Jesus identified in the religious establishment of His day. What began as one man’s theological inventions has become an institutional apparatus demanding conformity to traditions that find no warrant in the written Word of God.

This analysis proceeds from the conviction that biblical texts possess both historical meaning and contemporary application. If Matthew 23 served as Jesus’ definitive statement on the corruption of institutionalized religion, then those passages remain normative for evaluating religious movements that exhibit similar characteristics. The following examination considers six primary areas where critics and observers have identified parallels between Pharisaic Judaism and contemporary LDS practice.

The Letter That Kills: Legalism and the Neglect of Weightier Matters

Jesus’ indictment of the Pharisees reaches its theological apex in Matthew 23:23-24, where He declares: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you tithe mint and dill and cumin, and have neglected the weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faithfulness. These you ought to have done, without neglecting the others. You blind guides, straining out a gnat and swallowing a camel!” The critique is not that the Pharisees observed the law but that their meticulous attention to minutiae had displaced attention to the law’s fundamental moral demands.

Within Latter-day Saint culture, a similar pattern emerges in the elevation of specific behavioral requirements to positions of paramount importance. The Word of Wisdom, originally presented in Doctrine and Covenants 89 as counsel given “not by commandment or constraint,” has evolved into a rigorous code whose strict observance determines temple worthiness. The prohibition against coffee, tea, alcohol, and tobacco has assumed such centrality that a member’s standing before God is functionally measured by adherence to these dietary restrictions. Meanwhile, the “weightier matters”—justice toward the marginalized, mercy toward the struggling, faithfulness to the transforming work of grace—often receive rhetorical affirmation but structural subordination.

The Apostle Paul’s warning in 2 Corinthians 3:6 that “the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life” speaks directly to this tendency. When religious systems prioritize measurable compliance over heart transformation, they inevitably drift toward the very Pharisaism Jesus condemned. The LDS emphasis on quantifiable righteousness—attendance percentages, home teaching completion rates, Word of Wisdom compliance, tithing settlement interviews—creates a spiritual economy where the calculable displaces the transformative.

Building Fences Around the Law: The Multiplication of Regulations

The Pharisaic practice of building “fences around the Torah”—creating additional regulations to prevent accidental violation of biblical commands—represents one of the most distinctive features of Second Temple Judaism. The oral traditions that would eventually be codified in the Mishnah and Talmud emerged from this impulse to safeguard holiness through ever-more-specific behavioral prescriptions. Jesus addressed this directly in Mark 7:8-9: “You leave the commandment of God and hold to the tradition of men… You have a fine way of rejecting the commandment of God to establish your tradition!”

The LDS Church has developed an extensive body of detailed rules and cultural expectations that function analogously to the Pharisaic oral law—though in Mormonism’s case, much of this has been formally codified in official handbooks, temple preparation materials, and leadership guidance. The temple garment provides a particularly illuminating example. What began as sacred ceremonial clothing has expanded into a comprehensive daily dress requirement, with detailed guidance on when garments may be removed, how they should be worn, and what constitutes inappropriate modification or deviation. The Church’s General Handbook dedicates specific sections to garment-wearing expectations, and local leaders regularly counsel members on proper observance. These specifications have no biblical foundation and represent precisely the kind of tradition-building that characterized Pharisaic practice—the difference being that the LDS Church has institutionalized its extrabiblical requirements through official channels rather than leaving them to oral transmission.

Similarly, the Church’s extensive guidelines governing Sunday observance, dating behavior, media consumption, and even appropriate physical intimacy within marriage reflect the same regulatory impulse. The Strengthening Church Members Committee, the Church’s correlation program, and the detailed General Handbook of Instructions all function to codify behavioral expectations far beyond any biblical warrant. The result is a comprehensive behavioral framework that, like the Pharisaic system before it, seeks to ensure holiness through specification rather than transformation.

Phylacteries and Long Robes: External Performance and Religious Display

Jesus’ critique extended beyond merely behavioral prescription to address the motivations underlying religious practice. In Matthew 23:5-7, He observes: “They do all their deeds to be seen by others. For they make their phylacteries broad and their fringes long, and they love the place of honor at feasts and the best seats in the synagogues and greetings in the marketplaces and being called rabbi by others.” The Pharisees had transformed visible religious observance into a system of social capital, where external markers of piety served as credentials for public honor.

The parallel within LDS culture manifests in the social significance attached to visible markers of faithfulness. The temple recommend, a document certifying worthiness to enter LDS temples, functions as more than an access credential; it serves as a badge of spiritual standing within the community. Those who hold current recommends occupy a higher social tier than those who do not. The visible wearing of temple garments under clothing likewise serves as a marker of covenant faithfulness, creating a subtle hierarchy between the endowed and the unendowed, the compliant and the non-compliant.

Public callings within LDS congregations further reinforce this dynamic. The ward leadership structure—bishop, stake president, mission president, temple president—creates a visible hierarchy where higher callings confer greater social status. The public sustaining of leaders, the announcement of callings, and the structured seating arrangements at church functions all contribute to a culture where “the place of honor” carries tremendous weight. Jesus’ warning against such public religious performance could hardly be more relevant.

Based on my research, there is documentation to support the seating arrangement comment.

The General Handbook (section 29.2.1.1, item #3) explicitly states: “Presiding authorities and visiting high councilors should be invited to sit on the stand. General Officers are also invited to sit on the stand unless they are attending their home ward.”

Additional documentation shows:

- “The sacrament should be given first to the highest Church authority who sits on the stand and then passed to all others in an orderly way. A high councilor visiting a ward as an official representative of the stake presidency and sitting on the stand should be recognized by receiving the sacrament first, unless a General Authority or a member of the stake presidency is present on the stand.”

- The Salt Lake Tribune columnist Robert Kirby (a practicing Mormon) observed that “the LDS Church is one of the most hierarchal-appearing faiths in the world — outdone perhaps by only Catholicism and one or two others. It’s a trickle-down form of who’s the boss, reaching congregational levels where the bishop and counselors also have assigned seating.”

- Elder Boyd K. Packer’s talk “The Unwritten Order of Things” (1996 BYU Devotional) also addressed seating protocols, with one forum participant noting that “The one who presides in a meeting should sit on the stand and sit close to the one conducting. It is a bit difficult to preside over a meeting from the congregation.”

So yes, the statement about “structured seating arrangements” is supportable—the LDS Church has formal protocols about who sits on the stand, the order in which sacrament is passed based on hierarchical rank, and recognition of visiting authorities. The statement stands on solid ground.

Sitting in Moses’ Seat: The Authority of Institutional Interpretation

Matthew 23:2-3 opens Jesus’ discourse with a telling observation: “The scribes and the Pharisees sit on Moses’ seat, so do and observe whatever they tell you, but not the works they do. For they preach, but do not practice.” The scribes had positioned themselves as the authoritative interpreters of divine revelation, the indispensable mediators between God’s word and God’s people. This hermeneutical monopoly concentrated religious authority in the hands of a learned elite and marginalized individual engagement with Scripture.

The LDS Church has established an even more comprehensive system of interpretive authority through its doctrine of living prophets and continuing revelation. The principle that “when the prophet speaks, the debate is over” effectively subordinates Scripture to institutional pronouncement. The Standard Works—the Bible, Book of Mormon, Doctrine and Covenants, and Pearl of Great Price—are understood to be interpreted authoritatively only by the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Individual members are explicitly discouraged from reaching conclusions that differ from official Church interpretation, regardless of what their personal study of Scripture might suggest.

There is excellent documentation on this fact. Ezra Taft Benson’s 1980 BYU Devotional “Fourteen Fundamentals in Following the Prophet” provides explicit documentation. Here are the key quotes:

Second Fundamental: “The living prophet is more vital to us than the standard works.”

Benson quotes Brigham Young who reportedly said: “when compared with the living oracles those books are nothing to me; those books do not convey the word of God direct to us now, as do the words of a Prophet or a man bearing the Holy Priesthood in our day and generation. I would rather have the living oracles than all the writing in the books.”

Fifth Fundamental: “The prophet is not required to have any particular earthly training or credentials to speak on any subject or act on any matter at any time.”

Benson states: “if there is ever a conflict between earthly knowledge and the words of the prophet, you stand with the prophet, and you’ll be blessed and time will vindicate you.”

Eleventh Fundamental: “The two groups who have the greatest difficulty in following the prophet are the proud who are learned and the proud who are rich.”

Benson elaborates: “The learned may feel the prophet is only inspired when he agrees with them; otherwise, the prophet is just giving his opinion—speaking as a man.”

Additionally, from another LDS blog source, General Authorities are instructed: “In order to preserve the uniformity of doctrinal and policy interpretation, you are asked to refer to the Office of the First Presidency for consideration [of] any doctrinal or policy questions which are not clearly defined in the scriptures or in the General Handbook of Instructions.” In this way, conflict and confusion and differing opinions are eliminated. LDS Blogs

And from an official Church article: “Personal revelation from the Lord can confirm what the prophet teaches; it will not contradict revelation He gives to His prophets.”

This interpretive structure directly contradicts the Protestant Reformation’s recovery of the priesthood of all believers and the right of private judgment. More fundamentally, it replicates the precise error Jesus identified in the scribal class: the interposition of human authority between God and the individual soul. The Spirit’s ministry to illuminate Scripture for individual believers (John 16:13; 1 John 2:27) is effectively displaced by institutional pronouncement. “You search the Scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life,” Jesus told the religious leaders of His day, “and it is they that bear witness about me” (John 5:39). When institutional authority supersedes personal engagement with the biblical text, the Scriptures’ christocentric witness becomes obscured by institutional agendas.

The Synagogue of the Righteous: Judgmentalism and Religious Exclusivity

The Pharisaic self-understanding as the righteous remnant within Israel created a spiritual ecosystem characterized by exclusivity and judgment. The very name “Pharisee,” derived from the Hebrew parush (“separated one”), encoded this identity as those set apart from the common, unclean masses. This self-perception found expression in prayers like that attributed to the Pharisee in Luke 18:11: “God, I thank you that I am not like other men, extortioners, unjust, adulterers, or even like this tax collector.” Such prayers were not mere caricatures but reflected an actual spiritual posture documented in Second Temple literature.

LDS culture has developed its own forms of religious boundary-marking that produce similar dynamics. The division between “worthy” and “unworthy” members, mediated through the temple recommend interview process, creates a two-tier spiritual citizenship. Those without recommends—whether due to Word of Wisdom violations, tithing shortfalls, chastity concerns, or doctrinal doubts—are excluded not merely from temple ordinances but from full participation in the community’s most sacred events: sealings, endowments, and the weddings of family members.

This exclusionary structure generates what sociologists term “boundary maintenance,” the social processes by which communities define and enforce the distinction between insiders and outsiders. The judgmental culture that often accompanies such boundary maintenance is not incidental but structural: when worthiness is defined by measurable compliance with institutional requirements, those who fail to comply become objects of judgment rather than recipients of grace. The “holier-than-thou” attitude Jesus condemned emerges naturally from religious systems that define holiness in terms of external conformity rather than inner transformation by divine grace.

Gatekeepers to the Divine: The Temple Recommend System and Access to God

Jesus’ most severe condemnation addresses the Pharisees’ role as religious gatekeepers: “But woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you shut the kingdom of heaven in people’s faces. For you neither enter yourselves nor allow those who would enter to go in” (Matthew 23:13). The religious establishment had positioned itself between seeking souls and the God they sought, transforming what should have been a ministry of mediation into a mechanism of exclusion.

The LDS temple recommend system functions as precisely such a gatekeeping mechanism. Access to temple ordinances—which LDS theology regards as essential for exaltation—requires passing a series of intrusive personal interviews with local ecclesiastical leaders. These interviews probe not only behavioral compliance (Word of Wisdom, tithing, chastity) but also doctrinal conformity (sustaining Church leadership, accepting current prophetic authority) and even the most intimate aspects of personal life. The bishop and stake president function as gatekeepers whose approval determines access to ordinances presented as necessary for salvation.

This system stands in stark contrast to the New Testament’s proclamation of direct access to God through Christ. The author of Hebrews declares that through Jesus we may “with confidence draw near to the throne of grace” (Hebrews 4:16), and that the new covenant provides “a new and living way” into God’s presence (Hebrews 10:19-20). The veil of the temple was torn at Christ’s crucifixion precisely to signify the abolition of mediated access to divine presence. Any religious system that reconstructs such barriers—whether through priestly hierarchy, sacramental necessity, or institutional gatekeeping—reverses the accomplishment of Calvary.

Theological Synthesis: From Whole Cloth to Whitewashed Tombs

The theological innovations introduced by Joseph Smith and elaborated by his successors represent what can only be described as doctrines generated “from whole cloth,” lacking any genuine biblical foundation. The pre-existence of human spirits, the plurality of gods, the potential for human deification, the three degrees of glory, baptism for the dead, eternal marriage as a salvific ordinance, and the necessity of temple rituals for exaltation—none of these doctrines emerge from responsible exegesis of the biblical text. They represent instead the creative theological speculation of nineteenth-century religious imagination, subsequently institutionalized into a comprehensive system of belief and practice.

What makes these innovations particularly troubling is not merely their non-biblical character but the religious infrastructure constructed to enforce them. The LDS Church has built an elaborate system of interviews, recommend requirements, worthiness standards, and disciplinary procedures to ensure compliance with these extra-biblical mandates. Members who question these doctrines or practices face social marginalization and, in extreme cases, formal ecclesiastical discipline.

The case of Douglas Stilgoe, the British YouTuber known as “Nemo the Mormon,” provides a contemporary illustration of this enforcement mechanism in action. Stilgoe, a returned missionary who graduated from seminary with perfect attendance, began using his platform to call for transparency and accountability from LDS leadership—addressing concerns about the Church’s handling of its vast wealth, nepotism among leadership, and what he documented as patterns of dishonesty among the First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve. He even sent a 3,500-word letter to Church headquarters outlining his concerns and successfully campaigned alongside other British Latter-day Saints for mandatory background checks on Church volunteers who work with children—a basic safeguarding measure the institution had resisted. Yet rather than engage his substantive criticisms, the Church convened a disciplinary council in Oxford, England, in September 2024, and withdrew his membership. The official letter claimed his “persistent efforts to persuade others” constituted leading members astray—though Stilgoe maintained he was simply calling for the kind of honest self-reflection any healthy organization should welcome.

Notably, leaked training materials suggest that President Dallin H. Oaks has been actively encouraging local leaders to hold more such disciplinary councils. The message is unmistakable: public questioning of leadership, even when grounded in documented facts and motivated by genuine concern for the Church’s integrity, will be met with the ultimate sanction of spiritual exile. The result is a religious culture characterized by precisely the dynamics Jesus condemned: external conformity without internal freedom, institutional authority without spiritual liberty, visible righteousness without heart transformation.

Jesus’ image of “whitewashed tombs” captures this dynamic with devastating precision: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you are like whitewashed tombs, which outwardly appear beautiful, but within are full of dead people’s bones and all uncleanness. So you also outwardly appear righteous to others, but within you are full of hypocrisy and lawlessness” (Matthew 23:27-28). The danger of any religious system built on external compliance is that it produces exactly this result: an outward appearance of righteousness that may mask inner spiritual death. The person who meticulously observes the Word of Wisdom, faithfully pays tithing, regularly wears garments, and passes all recommend interviews may nevertheless remain unregenerate—a “whitewashed tomb” appearing beautiful externally while remaining spiritually dead within.

Conclusion: The Continuing Prophetic Witness

The parallels between Pharisaic Judaism as critiqued by Jesus and contemporary LDS religious culture are neither superficial nor incidental. They represent the predictable outcome of any religious system that substitutes institutional compliance for spiritual transformation, human tradition for divine revelation, and external conformity for internal renewal.

Modern LDS pomp and ceremony is something to behold in its apparent spectacle—the gleaming temples with their manicured grounds, the choreographed general conferences broadcast worldwide, the elaborate ritual garments and sacred ordinances performed behind closed doors. Yet this impressive window dressing covers over two centuries of compounding religious error. Joseph Smith’s retention of sufficient Christian vocabulary to maintain apparent continuity with the broader Christian tradition, combined with his introduction of theological and practical innovations without biblical warrant, created a religious movement that recapitulates the very errors Jesus condemned. The whitewashed exterior—impressive architecture, institutional efficiency, and a veneer of Christian piety—conceals the same hollow core that prompted Christ’s searing rebuke: “You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of the bones of the dead” (Matthew 23:27).

This analysis is offered not in a spirit of religious antagonism but of genuine concern. The well-meaning and sincere souls drawn to the LDS Church deserve to encounter the true Gospel: that salvation is by grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone, revealed in Scripture alone, to the glory of God alone. They deserve freedom from the burden of institutional requirements presented as necessary for salvation. They deserve direct access to God through the finished work of Christ without the mediation of ecclesiastical gatekeepers. They deserve the liberty of the Spirit rather than the bondage of religious legalism.

Matthew 23 remains as relevant today as when Jesus first pronounced its woes. Its prophetic witness continues to expose religious systems that “tie up heavy burdens, hard to bear, and lay them on people’s shoulders” while refusing to “move them with their finger” (Matthew 23:4). The seven woes speak to every generation, warning against the perennial human tendency to transform encounter with the living God into compliance with institutional demands. May those with ears to hear discern the continuing relevance of this prophetic word—and may they find in Christ the freedom that religious systems can never provide.

* * *