From Divine Inspiration to Modern Translation:

Tracing the Journey of Scripture Through the Ages

Download a PDF for printing at home: Bible Translations

Introduction

The Bible stands as the most influential book in human history, shaping civilizations, inspiring movements, and providing spiritual guidance to billions. Yet few understand the remarkable journey this collection of sacred texts has taken from its origins in the ancient Near East to the modern translations that grace our bookshelves today. This comprehensive examination traces the canonization of Scripture and its translation through the millennia, addressing both the triumphs and challenges inherent in preserving and transmitting the Word of God across languages and cultures.

The story of the Bible’s formation and transmission is not merely an academic exercise—it goes to the heart of questions about divine revelation, textual authority, and the reliability of Scripture itself. How can we be confident that the words we read today accurately reflect what the original authors penned millennia ago? What processes determined which books would be included in the biblical canon? And how should modern believers navigate the proliferation of contemporary translations?

These questions become even more pressing when we consider the various challenges leveled against biblical reliability throughout history. From ancient Gnostic claims of hidden gospels to modern accusations of ecclesiastical corruption, from translation controversies to textual criticism debates, the Bible has faced sustained scrutiny regarding its authenticity and accuracy. This study aims to provide a comprehensive examination of these issues, drawing on the latest scholarship while upholding a commitment to the historic Christian understanding of Scripture as the inspired Word of God.

The Foundation: Oral Tradition and Early Written Records

Before written Scripture emerged, oral tradition played a crucial role in preserving divine revelation. The ancient Near Eastern world operated primarily through oral communication, with written records supplementing rather than replacing spoken tradition. This wasn’t casual storytelling but systematic preservation of sacred content.

Hebrew tradition embedded oral transmission deeply in cultural and religious practice. The Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4-9) commanded parents to teach God’s words constantly to their children. Professional scribes and teachers emerged whose primary responsibility was maintaining transmission accuracy.

Oral tradition achieved remarkable stability through three mechanisms: poetic and rhythmic structures made memorization easier and errors detectable; communal recitation and cross-checking prevented individual errors from becoming permanent; and the sacred nature of content motivated extraordinary care—these were God’s very words, not mere historical records.

Archaeological discoveries validate this reliability. The Dead Sea Scrolls (1947) provided Hebrew manuscripts nearly 1,000 years older than previously known texts, yet showed remarkable consistency with later manuscripts. The Great Isaiah Scroll (c. 100 BCE) differs from the Masoretic text only in minor details affecting no doctrinal content.

The New Testament period continued these practices. Jesus’ teachings were preserved orally before being written, following established rabbinic methods. Paul referenced both written Scripture and oral tradition as authoritative (2 Thessalonians 2:15 — So then, brothers, stand firm and hold to the traditions that you were taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter.).

This oral foundation proved crucial when written records emerged. Early texts served to fix and standardize what had already been carefully preserved orally, explaining the consistency found across manuscript traditions—written texts were constrained by well-established oral traditions that would immediately detect significant deviations.

Written Transmission: From Autographs to Manuscripts

The transition from oral to written biblical transmission introduced both new preservation opportunities and potential copying errors. Hebrew scribes developed extraordinarily rigorous standards, with the Masoretes (6th-10th centuries CE) establishing unparalleled textual preservation methods. They meticulously counted words and letters, noted middle words of each book, and destroyed any manuscript containing errors rather than correcting them. This extreme care reflected their theological conviction that they were handling God’s very words, with Talmudic regulations governing everything from materials to scribal posture.

The New Testament possesses unprecedented manuscript evidence—over 5,000 Greek manuscripts ranging from papyrus fragments dating within decades of original composition to complete 4th-century Bibles. No other ancient document approaches this attestation level; most classical works survive in dozens rather than thousands of copies with centuries-long gaps.

While this abundance creates 300,000-400,000 textual variants, the vast majority represent minor spelling, word order, or synonym differences. Only about 1% impact textual meaning, and virtually none affect fundamental Christian doctrines.

Modern textual criticism employs sophisticated methods, examining external evidence (manuscript age, quality, geographical distribution) and internal evidence (authorial style, variant development). Recent discoveries like Papyrus 52 (c. 125 CE) and Papyrus 75 (c. 200 CE) demonstrate that accurate textual traditions were well-established by the 2nd century, supporting remarkable confidence in biblical text preservation.

The Original Languages to Early Versions: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek

Biblical translation fundamentally depends on understanding Scripture’s original languages: Hebrew (Old Testament), Aramaic (portions of Daniel, Ezra, Jeremiah), and Koine Greek (New Testament). Each language shaped how divine revelation was expressed and must inform translation efforts.

Hebrew, as the primary Old Testament vehicle, reflects ancient Israelite thought patterns—concrete rather than abstract, action-oriented rather than philosophical, communal rather than individual. Its consonantal writing system (vowels added later by Masoretes) provided remarkable stability, as consonants resist copying errors and context clarified meaning. The latter vowel points represented centuries of careful tradition, not speculation.

Aramaic sections reflect the period’s lingua franca and likely Jesus’ primary language. These passages offer crucial insights into exile and return contexts through official correspondence and governmental documents.

Koine Greek served New Testament revelation as the Hellenistic period’s marketplace language, accessible throughout the Mediterranean. This choice reflects Christianity’s universal scope—God communicated in the language reaching the widest audience, not elite classical Greek.

The Septuagint, a pre-Christian Greek translation of Hebrew Scripture (3rd-1st centuries BCE), bridged the Hebrew and Greek worlds. Extensively quoted by New Testament authors, it became the early church’s Bible while providing faithful Hebrew renderings and insights into ancient Jewish interpretation.

Early versions in Latin, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, and Gothic appeared within centuries, serving multiple scholarly purposes: providing textual witnesses for reconstruction, demonstrating early Christian understanding, and illustrating Christianity’s universal character. Quality varied, but their existence testifies to the early church’s commitment to linguistic accessibility—a commitment continuing today. Rather than requiring Hebrew or Greek conversion, believers immediately translated Scripture into local languages.

Canonization: The Formation of the Biblical Canon

The biblical canon—the authoritative collection of Scripture—represents one of religious history’s most significant processes, demonstrating both divine sovereignty and human responsibility in recognizing authentic revelation.

Hebrew Bible canonization occurred gradually over centuries. The Torah achieved recognition by Ezra’s time (5th century BCE), evidenced by the community’s response to its public reading (Nehemiah 8). The Prophets gained canonical status later, with the Prologue to Ecclesiasticus (c. 180 BCE) indicating their established authority. The Writings took the longest to achieve universal acceptance, with books like Ecclesiastes and Song of Songs facing questions into the Christian era.

The Council of Jamnia (c. 90 CE), often cited as “closing” the canon, actually confirmed rather than created it. The council addressed lingering questions but recognized what had already achieved practical authority in Jewish communities. This process reflects recognition rather than creation—authentic Scripture demonstrated authority through widespread acceptance and spiritual impact.

New Testament canonization followed similar patterns. The core documents—four Gospels and Paul’s major letters—achieved recognition within the first century. References in 2 Peter 3:15-16 to Paul’s letters as “Scripture” alongside the Old Testament demonstrate their rapid acceptance.

Canonical criteria, though never formally codified, can be discerned: apostolic authorship or connection provided primary authentication; orthodox theological content was essential; widespread geographical acceptance indicated divine authentication; liturgical usage demonstrated practical recognition of scriptural authority.

The process wasn’t uniform. Books like 2 Peter, James, and Revelation faced regional questions, while works like 1 Clement were highly regarded in certain communities. However, by the 4th century, a broad consensus emerged around today’s 27-book New Testament.

Contrary to misconceptions, canonization wasn’t controlled by a single authority making arbitrary decisions. The Council of Carthage (397 CE) ratified existing widespread acceptance rather than creating the canon. Constantine didn’t choose biblical books at Nicaea (325 CE)—that council addressed Christological controversies.

Apocryphal literature, while historically valuable, lacked the canonical books’ authenticating characteristics. Recent discoveries like the Nag Hammadi library offer insights into early Christian diversity but don’t challenge the canonical process, representing later developments with different theological perspectives.

The canonical process demonstrates divine providence working through human recognition rather than human creation of authority. Our Bible’s books earned their place through demonstrated spiritual power and apostolic authenticity rather than ecclesiastical politics, providing confidence that we possess the books God intended for his church.

The Rise of Vernacular Translations: Making Scripture Accessible

The translation of Scripture into vernacular languages represents one of history’s most democratizing movements, breaking barriers between learned clergy and ordinary believers while raising complex questions about interpretation, authority, and cultural adaptation.

Early vernacular translation efforts emerged from missionary necessity as Christianity spread beyond Jewish and Greco-Roman contexts. The Gothic Bible of Ulfilas (4th century), Syrian, Armenian, and Coptic versions established patterns influencing translation for centuries. Jerome’s Latin Vulgate (late 4th century) became Western Christianity’s most influential translation, serving for over a millennium through remarkable linguistic skill and textual sensitivity.

Medieval attitudes toward vernacular translation varied by region and period. The Waldensian movement (12th century) produced vernacular translations defying ecclesiastical restrictions, while Wycliffe’s English Bible (14th century) sparked both revival and institutional opposition. Church concerns weren’t unfounded—translation involves interpretation, and unauthorized versions could promote theological errors or social unrest.

Printing technology revolutionized biblical translation and distribution. Gutenberg’s Bible (c. 1455) demonstrated printing’s potential, while subsequent editions made Scripture increasingly accessible and ecclesiastical control difficult to maintain.

William Tyndale’s English New Testament (1526) marked a watershed moment. His democratic vision—“I will cause a boy that driveth the plough shall know more of the Scripture than thou doest”—combined exceptional linguistic skill with theological conviction. Tyndale established enduring translation principles: prioritizing accuracy to original languages over ecclesiastical tradition, consulting multiple sources, employing clear natural language, and including explanatory notes. Though executed in 1536 for his work, the movement proved unstoppable.

Martin Luther’s German Bible demonstrated vernacular translation’s theological potential, while the King James Version (1611) represented English translation’s culmination, achieving unprecedented literary beauty that shaped English culture for centuries.

Colonial expansion accelerated translation efforts as missionaries encountered unknown languages, requiring the development of writing systems and vocabularies for biblical concepts. By 1800, complete Bibles existed in 71 languages. The 19th-20th centuries witnessed explosive growth through organizations like the British and Foreign Bible Society (1804) and American Bible Society (1816), with modern linguists like William Cameron Townsend developing new methodologies.

Contemporary vernacular translation continues this heritage while facing new challenges. Globalization creates distribution opportunities but pressures for cultural accommodation. Digital technology enables rapid translation but raises quality control questions. The proliferation of English translations reflects both genuine philosophical diversity and market competition among publishers.

The Good and Bad of Modern Translation Processes

Modern biblical translation has achieved unprecedented linguistic sophistication and scholarly rigor, yet this advancement has introduced new complexities and controversies that require careful evaluation.

Positive Developments

Contemporary translators possess remarkable resources unavailable to previous generations. Archaeological discoveries have illuminated biblical backgrounds and clarified obscure terms, while comparative linguistics has deepened understanding of Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. Computer analysis identifies patterns across vast databases of ancient texts, and digital manuscript images enable direct consultation of primary sources.

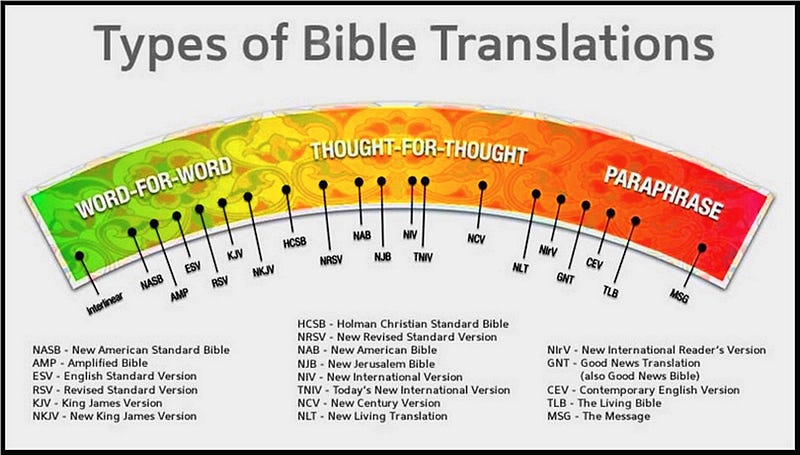

Modern translation teams typically include specialists in biblical languages, archaeology, linguistics, theology, and cultural anthropology. This multidisciplinary approach avoids single-scholar limitations while providing internal checks against theological bias or linguistic errors. Contemporary methodologies have become increasingly sophisticated in balancing formal equivalence (word-for-word accuracy) with dynamic equivalence (thought-for-thought clarity), maintaining fidelity to original meanings while achieving receptor language clarity.

Translation principles have matured significantly, with translators explicitly acknowledging interpretive assumptions, documenting methodological choices, and submitting work to scholarly review. This transparency allows readers to understand translation decisions and evaluate different approaches, promoting informed rather than blind acceptance.

Significant Challenges

However, modern translation faces serious problems. Bible publishing commercialization has created market pressures that don’t always serve textual fidelity. Publishers compete by promoting their versions as superior, sometimes making excessive claims. Copyright considerations can influence translation choices as publishers seek distinctive versions qualifying for legal protection.

Translation proliferation has created confusion among readers lacking the expertise to evaluate competing claims. When versions render passages substantially differently, ordinary readers may question whether any translation can be trusted, potentially undermining biblical authority rather than enhancing it.

Some translations exhibit concerning theological accommodation tendencies. The desire to make Scripture “relevant” sometimes leads to anachronistic renderings imposing modern concepts on ancient texts. Gender-inclusive language, while motivated by accessibility concerns, can obscure important theological distinctions or historical realities.

Most concerning is the tendency for translations to reflect specific theological or ideological agendas. The Jehovah’s Witnesses’ New World Translation exemplifies this problem, systematically altering passages related to Christ’s divinity to support Watchtower theology rather than reflecting natural Greek text understanding.

Balanced Approach

Despite these challenges, overall modern translation quality remains high. The best contemporary versions represent genuine improvements in accuracy, clarity, and cultural sensitivity. Readers who use multiple versions, consult study notes, and approach translation issues with appropriate humility can benefit enormously from modern scholarship while avoiding excessive reliance on any single version.

Which Translation Is Best? Navigating the Options

The question of which Bible translation is “best” reflects both legitimate scholarly concerns and unfortunate sectarian divisions within Christianity. Rather than searching for a single “perfect” translation, wise readers learn to appreciate the strengths and limitations of different approaches while developing principles for faithful biblical study.

The reality is that no single translation can perfectly capture all aspects of the original texts. Translation always involves interpretation, cultural adaptation, and linguistic compromise. What works well in one context may be less effective in another. The goal should not be finding the perfect translation but understanding how to use available translations faithfully and effectively.

What Are the 5 Most Accurate Bible Translations?

Other versions are worthy of attention, but these five are universally considered great for several reasons. First, they are all translated by respected and diverse groups of theologians. Second, they all stay fairly close to one another in attempting to give the best meaning to what the Scripture has to tell us today.

Different translations serve distinct purposes, making the “best” translation dependent on intended use. For serious Bible study, formal equivalence translations like the ESV, NASB, and NKJV prioritize word-for-word accuracy, maintaining original Hebrew and Greek structures despite challenging English readability. For general reading, dynamic equivalence versions like the NIV, NLT, and CEV emphasize thought-for-thought clarity in natural contemporary English, sacrificing precision for comprehensibility—ideal for new readers and public reading.

Balanced approaches exist: the CSB seeks “optimal equivalence” combining accuracy with readability, while the NET provides extensive translation notes. Serious students benefit from interlinear Bibles displaying original languages alongside English, enabling direct access to source texts and understanding of translation variations.

Quality evaluation requires multiple criteria: solid textual basis using best manuscripts, appropriate translation philosophy for the purpose, qualified translators with genuine linguistic expertise, and minimal denominational bias. Some translations fail significantly—the New World Translation alters Christ’s divinity passages for Jehovah’s Witness doctrine, the Joseph Smith Translation makes unsupported additions reflecting Mormon theology, and the Passion Translation reflects a charismatic agenda over scholarship.

Other versions show denominational influences but remain acceptable: the Jerusalem Bible reflects Catholic traditions, Orthodox Study Bible presents Eastern perspectives. These aren’t problematic if readers recognize the presented perspective.

Most readers benefit from multiple translations. Comparing renderings illuminates meaning better than single-version reliance, with significant disagreements indicating interpretive challenges requiring investigation. Study Bibles enhance value through explanatory notes, though these represent human interpretation without textual authority.

Digital resources transform Bible study, enabling instant version comparison and original language access, though requiring wisdom to prevent information overload.

The fundamental principle: seek God through His Word rather than defending linguistic preferences. The best translation facilitates biblical engagement, promotes spiritual growth, and enables faithful living—varying by individual, context, and purpose.

Churches must consider congregation needs, theological consistency, and pastoral wisdom. Scholar-friendly translations may confuse new believers, while clear contemporary versions might lack doctrinal precision. Wise leaders balance context with commitment to biblical truth and authority.

Defending Biblical Reliability: Responding to Corruption Claims

Biblical corruption claims—from Mormon “plain and precious truths” allegations to Muslim tahrif arguments—persistently challenge Scripture’s reliability. However, these accusations collapse under careful examination of manuscript evidence and transmission processes.

Critics often confuse transmission (copying accuracy) with translation (language rendering). Modern Bible versions translate directly from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek manuscripts—not through multiple language chains like telephone games. This single-step process preserves textual integrity.

The Bible’s manuscript evidence surpasses any ancient document. Over 5,000 Greek New Testament manuscripts exist, from papyrus fragments within decades of original composition to complete 4th-century Bibles. This abundance enables precise error identification and correction through comparison.

Manuscript variations, while numerous, are overwhelmingly minor—spelling differences, word order, or synonyms. Seventy-five percent of the New Testament shows no variation; 95% of the remaining variants are easily resolved. Less than 1.5% involves serious uncertainty, with no fundamental doctrines affected.

Manuscript “tenacity” actually protects rather than threatens textual integrity. Once readings enter the tradition, they persist—even obvious errors—meaning original readings remain preserved among variants. This makes large-scale corruption impossible; systematic alterations would be immediately detectable across geographically distributed manuscripts.

Claims about massive textual removal face insurmountable practical obstacles. How could any organization secretly gather thousands of copies spread from Spain to Egypt—including manuscripts buried in Egyptian sands or Palestinian caves—alter them consistently, and replace them undetected?

Archaeological discoveries confirm rather than undermine reliability. Dead Sea Scrolls (1947) provided Hebrew texts nearly 1,000 years older than previously known, showing remarkable consistency with later copies. Early papyri like P52 (c. 125 CE) demonstrate accurate textual traditions within decades of composition.

Early versions (Latin, Syriac, Coptic) provide additional protection, preserving independent textual witnesses that would detect systematic alterations. Professional scribal practices, especially among Hebrew Masoretes, demonstrated extraordinary care—counting words and letters, destroying error-containing manuscripts rather than correcting them.

Ironically, those claiming biblical corruption often promote texts with documented alterations. The Book of Mormon underwent thousands of changes since 1830, while the Doctrine and Covenants shows extensive editing. If textual modification indicates unreliability, these scriptures face far greater challenges than the Bible.

Contemporary textual criticism employs sophisticated methods to analyze manuscript age, quality, distribution, and internal evidence. These enable confident reconstruction of original texts, providing solid foundations for biblical study and Christian faith.

James White vs LDS Translation and Corruption Claims

In responding to the fictitious Mormon Elder Hahn’s claims about biblical corruption, James White, in his book, Letters To A Mormon Elder, systematically dismantles the common LDS assertion that the Bible has been corrupted beyond reliability. White first clarifies the crucial distinction between transmission (copying manuscripts) and translation (rendering text into other languages), explaining that modern English Bibles translate directly from Hebrew and Greek originals, not through multiple language chains like a game of telephone. White emphasizes that when Mormons claim the Bible has been “translated over and over and over again,” they misunderstand the actual process—imagining a sequential chain from Hebrew to Greek to Latin to French to German to Spanish to English, when in reality each English version is based directly on the original languages with only one step between the Hebrew/Greek texts and English translation.

This fundamental confusion between transmission (how manuscripts were copied and preserved over time) and translation (how texts are rendered from one language to another) underlies most Mormon objections to biblical reliability. He demonstrates that over 5,000 Greek New Testament manuscripts exist, with 75% of the text showing no variation and 95% of remaining variants easily resolved through textual criticism, leaving less than 1.5% with any uncertainty—none affecting core doctrines.

White argues that the manuscript tradition’s “tenacity” actually protects the text since original readings remain preserved among variants, making systematic corruption impossible across thousands of manuscripts spread throughout the ancient world. He exposes the inconsistency of LDS claims by noting that Mormons dismiss biblical passages contradicting LDS doctrine as “mistranslated” without linguistic evidence, while ironically, the Book of Mormon itself has undergone thousands of changes since 1830, far more than any biblical manuscript variations.

The King James Only Controversy: Examining an Unnecessary Division

The King James Only movement represents one of contemporary Christianity’s most divisive translation controversies, creating unnecessary divisions over secondary issues while obscuring fundamental questions of biblical authority.

KJV Only advocates claim loyalty to the Textus Receptus, arguing that God guided Erasmus to produce a Greek text identical to the original manuscripts. However, this faces significant problems. The Textus Receptus underwent multiple revisions, and Erasmus acknowledged errors in his hasty first edition. More tellingly, KJV advocates reject even the New King James Version, which uses the same Textus Receptus, revealing loyalty to specific English wording rather than a textual basis. Modern updates like the KJ21 and MEV, which merely modernize archaic language while retaining identical manuscripts, face similar rejection.

Legitimate concerns underlying KJV preference include worries about theological liberalism, commercial motivations, and version proliferation, creating confusion. However, extreme claims cannot withstand scrutiny. The KJV translators worked with fewer, later manuscripts than are available today and acknowledged their work’s provisional nature.

The movement’s English-focused thinking creates problematic cultural chauvinism—why should English speakers read archaic language while other languages receive contemporary translations? Biblical translation should follow original composition patterns: Scripture was written in common, everyday language, not elevated speech. Contemporary translations should communicate similarly.

The KJV remains valuable for its scholarly achievement, literary artistry, and devotional significance. However, our loyalty should be to original Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek manuscripts, not any English translation. No modern translation is perfect; comparing multiple versions often provides a better understanding than relying on one.

Christians should prioritize unity over translation preferences, exercise pastoral wisdom for congregational contexts, and ground confidence in God’s faithful preservation of his Word across languages and centuries rather than in one specific translation.

Conclusion: Confidence in God’s Preserved Word

The journey from oral tradition to modern translation reveals divine sovereignty working through human responsibility to preserve God’s Word across millennia. Despite involving human agents with historical limitations, the biblical text’s remarkable consistency testifies to providential care extending across cultures and centuries.

It must also be appreciated that no translation is totally literal all of the time. It is not a simple process of finding one English word for each Greek and Hebrew word. Furthermore, words cannot be translated in isolation. Each language has its own set of idiomatic expressions that do not make sense when translated literally. If the Scripture were to be translated in a literal, or word-for-word, manner in every passage, then the result would often be unreadable or non-understandable. Idioms have to be explained — not translated word-for-word.

Evidence for biblical reliability is overwhelming when examined comprehensively. Abundant manuscript evidence, careful ancient scribal practices, early vernacular translations, and rigorous modern textual criticism all support confidence that we possess substantially what the original authors wrote. Claims of massive corruption cannot withstand honest historical investigation.

Translation diversity reminds us that rendering Scripture requires linguistic expertise, cultural sensitivity, and spiritual discernment. While no single translation perfectly captures every aspect of original texts, faithful translations effectively communicate biblical truth across linguistic barriers. Modern English translation proliferation demonstrates Scripture’s vitality rather than undermining biblical authority.

Multiple translations can enhance biblical understanding when approached with wisdom and humility. The key lies in understanding translation principles, recognizing different approaches’ strengths and limitations, and maintaining commitment to biblical truth over linguistic preferences.

Contemporary Christians should approach this heritage with confidence and humility. Confidence, because our faith’s textual foundation rests on solid historical ground—the Bible we read today faithfully represents God’s revelation through prophets, apostles, and his Son. Humility, because translation and interpretation require ongoing diligence, scholarly investigation, and dependence on the Holy Spirit’s illumination.

The ultimate test of any translation is not linguistic perfection but its capacity to facilitate a genuine encounter with the living God. As Isaiah declared, God’s word accomplishes his purposes (Isaiah 55:11 KJV), assuring believers that faithful Scripture engagement opens pathways to divine truth and spiritual transformation regardless of the specific translation used.

So shall my word be that goeth forth out of my mouth:

it shall not return unto me void, but it shall

accomplish that which I please, and it

shall prosper in the thing whereto I sent it.

About this post: This comprehensive study draws upon decades of biblical scholarship, textual criticism, and translation theory to provide readers with a thorough understanding of how Scripture has been preserved and transmitted throughout history. The evidence presented here supports confidence in biblical reliability while acknowledging the human dimensions of preservation and translation processes.