A Comparative Theological Analysis:

“Are Mormons Christian?” Series

1. Introduction: The Question of Christological Orthodoxy

Few theological questions carry greater weight than the identity and nature of Jesus Christ. Throughout the history of the Christian church, Christological controversies have generated some of the most significant councils, creeds, and theological treatises in ecclesiastical history. From the Councils of Nicaea (325 AD) and Chalcedon (451 AD) to the present day, the church has recognized that one’s understanding of Christ determines whether one stands within or outside the bounds of Christian orthodoxy. The emergence of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in nineteenth-century America has presented contemporary Christianity with a movement that uses Christian vocabulary and centers its worship on a figure named Jesus Christ, yet articulates a fundamentally different understanding of who Christ is, what his nature entails, and how salvation is accomplished through him.

This article undertakes a systematic examination of Latter-day Saint (LDS) Christology in comparison with the orthodox Christian understanding that has been transmitted through Scripture, the early Church Fathers, the ecumenical councils, and two millennia of theological reflection. The purpose is not to engage in polemics but to provide scholarly clarity regarding the substantive differences that exist between these two theological systems. These differences are not peripheral matters of practice or secondary doctrine; they concern the very identity of the One whom Christians worship as Lord and Savior. A clear-eyed assessment of these differences is essential for anyone seeking to understand the relationship between LDS theology and historic Christianity.

The analysis that follows will demonstrate that LDS Christology, despite its use of traditional Christian terminology, presents a fundamentally different understanding of Christ’s person, nature, origins, incarnation, and atoning work. These differences are not merely semantic variations but represent a departure from the biblical and creedal foundations that have defined Christian faith since the apostolic era. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for theological dialogue, missionary engagement, and the maintenance of doctrinal integrity within the Christian community.

2. Introduction to Latter-day Saint Theology

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints emerged from the religious ferment of early nineteenth-century America, founded by Joseph Smith Jr. in 1830 in upstate New York. Smith claimed to have received divine revelations, beginning with a theophany in 1820 (the “First Vision”) and continuing through the translation of the Book of Mormon from golden plates and subsequent canonical texts, including the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price. These additional scriptures, along with continuing prophetic revelation through church leaders, provide the doctrinal foundation for LDS theology, supplementing and, in practice, often reinterpreting the biblical text.

Central to understanding LDS Christology is the broader LDS cosmology and doctrine of God. LDS theology teaches that God the Father (Heavenly Father) is an exalted man with a tangible body of flesh and bones, who progressed to godhood and now dwells with a divine consort (Heavenly Mother) near the star Kolob (this aspect is officially denied). All human beings, including Jesus Christ and Lucifer, are understood to be literal spirit children of these Heavenly Parents, conceived in a premortal existence before their earthly incarnation. This cosmological framework fundamentally shapes how Latter-day Saints understand the identity and work of Jesus Christ, positioning him not as the eternally divine Second Person of the Trinity but as the firstborn spirit offspring in a cosmic family.

Key LDS texts informing Christology include the Book of Mormon (particularly 2 Nephi, Mosiah, and 3 Nephi), the Doctrine and Covenants, the Pearl of Great Price (especially the Books of Moses and Abraham), and authoritative teachings from LDS prophets and apostles. Works such as James Talmage’s Jesus the Christ (1915) and Bruce R. McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine (1958) have been particularly influential in shaping LDS understanding of Christ, though the latter has been officially discontinued from publication.

3. Overview of Orthodox Christian Doctrine

Orthodox Christian Christology finds its normative expression in the ecumenical creeds and councils of the early church, particularly the Nicene Creed (325 AD, expanded 381 AD) and the Definition of Chalcedon (451 AD). These formulations represent the church’s careful articulation of biblical teaching in response to various heresies that threatened to distort the apostolic faith. The Nicene Creed confesses that Jesus Christ is “the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.” The Definition of Chalcedon further clarifies that Christ exists “in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation”—fully divine and fully human in one person.

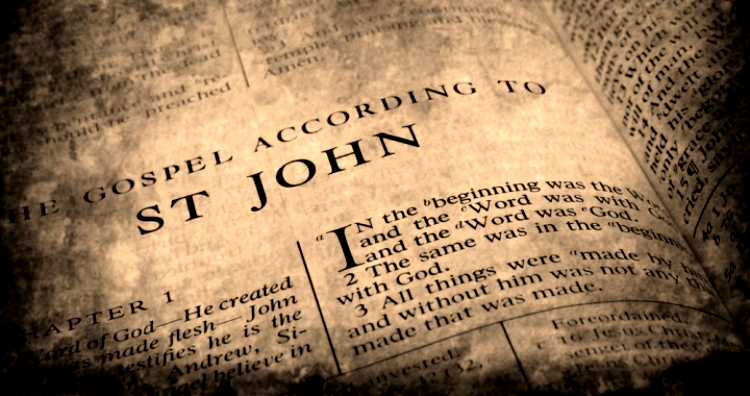

The foundations of orthodox Christology rest firmly upon Scripture. The Prologue to John’s Gospel declares that “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made” (John 1:1-3, ESV). The preexistent, eternally divine Logos became flesh (John 1:14), not by ceasing to be God but by assuming human nature in addition to his divine nature. The Apostle Paul affirms that in Christ “the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily” (Colossians 2:9) and that he is “the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible” (Colossians 1:15-16). The author of Hebrews declares that the Son is “the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature,” who “upholds the universe by the word of his power” (Hebrews 1:3).

The Church Fathers consistently defended and elaborated upon these truths. Athanasius of Alexandria championed the eternal deity of Christ against Arianism; the Cappadocian Fathers clarified Trinitarian distinctions; Cyril of Alexandria defended the unity of Christ’s person against Nestorianism. This theological heritage, refined through centuries of reflection and preserved across Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant traditions, represents the consensual Christian understanding of who Jesus Christ is. It is against this backdrop that LDS Christology must be evaluated.

4. Comparative Analysis of Christological Doctrines

4.1 The Nature and Origin of Christ

The most fundamental divergence between LDS and orthodox Christology concerns the very nature and origin of Jesus Christ. LDS doctrine teaches that Jesus is the “firstborn” spirit child of Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother in a premortal existence (Gospel Principles, chapter 3; Abraham 3:22-28). According to this teaching, all human spirits—including Jesus and Lucifer—were literally begotten by the Heavenly Parents before the creation of the earth. Jesus holds a position of primacy as the eldest spirit brother, but his relationship to the Father and to humanity is one of degree rather than kind. He is ontologically continuous with created beings, differing from other spirits in his faithfulness and premortal calling rather than in his essential nature.

Orthodox Christianity understands Christ’s nature in categorically different terms. The Nicene affirmation that Christ is “begotten, not made” specifically addresses this distinction. The Greek term homoousios (“of one substance” or “of the same essence”) was employed to affirm that the Son shares the identical divine nature with the Father—not a similar nature, not a derived nature, but the selfsame divine essence. The eternal generation of the Son is not a temporal act of procreation but an eternal relation within the Godhead. As the Athanasian Creed states, the Son is “God of the substance of the Father, begotten before the worlds.” He is not the first creation but the uncreated Creator through whom all things came into being.

John 1:1-3 makes this unmistakably clear. The Logos existed “in the beginning”—the same phrase used in Genesis 1:1 to describe the eternal God before creation. The Word “was with God” (indicating personal distinction) and “was God” (indicating essential deity). Through the Word, “all things were made, and without him was not any thing made that was made.” If Christ made all things without exception, he cannot himself be among the things made. The LDS position that Christ is the firstborn among created spirit offspring directly contradicts this foundational biblical testimony. The difference here is not semantic; it concerns whether Christ is the Creator or a creature, whether worship of Him is appropriate or idolatrous.

4.2 The Incarnation and Virgin Birth

A second area of significant divergence concerns the incarnation and virgin birth of Christ. Some historical LDS leaders, including Brigham Young and Bruce R. McConkie, taught or implied that Christ’s physical body was begotten through a literal physical relationship between God the Father (in his tangible, glorified body of flesh and bones) and the Virgin Mary. Brigham Young stated, “The birth of the Saviour was as natural as are the births of our children; it was the result of natural action” (Journal of Discourses 8:115). While the contemporary LDS church has distanced itself from explicit articulations of this doctrine, it has not officially repudiated it, and the underlying theology of God the Father possessing a physical body remains standard LDS teaching.

Orthodox Christianity has consistently affirmed the virgin birth as a miraculous work of the Holy Spirit without physical procreation. The angel Gabriel declared to Mary, “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be called holy—the Son of God” (Luke 1:35). Matthew’s Gospel explicitly states that Mary “was found to be with child from the Holy Spirit.” He quotes Isaiah’s prophecy: “Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son” (Matthew 1:18, 23). The Apostles’ Creed confesses that Jesus was “conceived by the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary.”

The theological significance of this difference cannot be overstated. The historical LDS position echoes ancient pagan mythologies in which gods physically mate with human women—precisely the kind of teaching the early church explicitly rejected. The incarnation in orthodox theology is the assumption of human nature by the eternally divine Logos, not the physical procreation of a demigod. The virginal conception demonstrates that salvation comes entirely from God, not from any human contribution, and preserves the unique nature of Christ as fully God and fully man without the confusion of divine and human essences through physical generation.

4.3 The Atonement: Gethsemane and Calvary

LDS theology places distinctive emphasis on the Garden of Gethsemane as the primary location of Christ’s atoning work. According to this view, Christ’s suffering for human sins began and was principally accomplished in the garden, where he took upon himself the sins of the world and experienced the full weight of divine judgment. The Book of Mormon states that Christ “suffereth the pains of all men, yea, the pains of every living creature, both men, women, and children, who belong to the family of Adam” (2 Nephi 9:21). Doctrine and Covenants 19:16-19 presents Christ himself describing his Gethsemane suffering: “Which suffering caused myself, even God, the greatest of all, to tremble because of pain, and to bleed at every pore, and to suffer both body and spirit.” While the cross is acknowledged in LDS teaching, Gethsemane receives theological priority in much LDS discourse.

This theological prioritization of Gethsemane over Calvary helps explain the conspicuous absence of crosses in LDS religious practice and architecture. Unlike virtually every other Christian tradition, LDS churches and temples display no crosses on their buildings, and members are discouraged from wearing crosses as personal jewelry. Church leaders have historically justified this by suggesting the cross represents the instrument of Christ’s death rather than a symbol of his triumph, with some comparing it to commemorating a loved one’s murder by wearing a replica of the weapon used. However, this explanation obscures a deeper theological function: by diminishing the cross, LDS teaching can more easily redirect attention to Gethsemane—a move that supports distinctive Mormon doctrines about the nature of atonement that differ significantly from orthodox Christianity’s emphasis on Christ’s substitutionary death and bodily resurrection. The empty cross in Protestant tradition or the crucifix in Catholic practice both center the faith on Calvary’s finished work; removing this symbol altogether creates theological space for an alternative soteriology built around temple ordinances, progressive exaltation, and the unique authority claims of the LDS priesthood.

We should note that early Latter-day Saints did not avoid the cross; 19th‑century Latter-day Saint marriage certificates, quilts, funeral programs, and even the 1852 European edition of the Doctrine and Covenants sometimes featured crosses. Early members, including prominent figures like Amelia Folsom Young, Nabby Young Clawson, and Benjamin F. Johnson, also wore cross jewelry in formal photographs, indicating that such accessories were relatively common among Latter-day Saints at the time.

Orthodox Christianity has consistently centered the atonement on Christ’s death on the cross. The Apostle Paul declared, “I resolved to know nothing while I was with you except Jesus Christ and him crucified” (1 Corinthians 2:2). The author of Hebrews emphasizes that “without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins” (Hebrews 9:22) and that Christ “entered once for all into the holy places, not by means of the blood of goats and calves but by means of his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption” (Hebrews 9:12). Peter writes that Christ “bore our sins in his body on the tree” (1 Peter 2:24). The early church understood Gethsemane as the place of Christ’s preparatory anguish, his submission to the Father’s will in anticipation of the cross, but Calvary was the location where the atoning sacrifice was accomplished.

This distinction matters theologically because the biblical witness consistently connects atonement with sacrificial death. The Levitical system required the death of the animal; the Passover lamb was slain; the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53 is said to have been “cut off out of the land of the living” and to have “poured out his soul to death” (Isaiah 53:8, 12). The atonement is not merely suffering but substitutionary death—the innocent dying in place of the guilty. To relocate the atonement primarily to Gethsemane obscures this biblical pattern and diminishes the centrality of the cross that pervades apostolic preaching and the subsequent theological tradition.

5. Implications for Faith and Practice

The Christological differences outlined above carry profound implications for faith and practice. If Jesus Christ is a created spirit offspring of Heavenly Parents—however exalted—rather than the eternally divine Son who shares the Father’s essence, then worship directed toward him takes on a different character. Orthodox Christianity worships Christ as God because he is God; the LDS Jesus, being ontologically continuous with humanity, occupies a different position in the cosmic order. Similarly, if Christ’s physical body resulted from divine-human procreation rather than the miraculous work of the Spirit, the incarnation loses its character as pure divine initiative and grace.

The implications extend to soteriology—the doctrine of salvation. In orthodox Christianity, only the infinite God can offer an infinite atonement sufficient for the sins of the world. The doctrine of Christ’s full deity is not abstract speculation but has direct bearing on the sufficiency and efficacy of his saving work. If Christ is not truly God, his sacrifice cannot secure eternal redemption for creatures who have sinned against an infinite God. The early church recognized this: Athanasius argued that only the Creator could recreate fallen humanity, only the immortal One could conquer death.

Furthermore, LDS theology includes doctrines of eternal progression wherein faithful Latter-day Saints may themselves attain godhood—the culmination of a trajectory that began with premortal spirit existence, continues through mortal probation, and extends into celestial exaltation. This cosmological framework fundamentally differs from the Christian understanding of the Creator-creature distinction. In orthodox Christianity, human beings may be glorified, adopted as children of God, and transformed into the likeness of Christ, but they never become gods in the sense of sharing the divine essence. The LDS doctrine of deification erases the ontological boundary between Creator and creature that Scripture and Christian tradition have consistently maintained.

6. Conclusion

The systematic examination of LDS Christology alongside orthodox Christian doctrine reveals not peripheral disagreements but fundamental divergences concerning the identity and nature of Jesus Christ. The differences involve whether Christ is the eternal God or created spirit offspring, whether the incarnation was miraculous or physical procreation, and whether the atonement centers on the cross or primarily occurred in Gethsemane. These are not matters of emphasis or terminology but represent distinct theological systems built upon incompatible foundations.

The historic Christian faith, preserved in Scripture and articulated through the ecumenical creeds and councils, confesses that Jesus Christ is “very God of very God,” eternally begotten of the Father, consubstantial with the Father, through whom all things were made. He took on human nature through the miraculous work of the Holy Spirit, was born of the Virgin Mary, and accomplished our redemption through his death on the cross. This Christ is worthy of worship because he is God; this Christ can save because only God can save; this Christ reveals the Father because he shares the Father’s essence.

LDS theology, while using much of the same vocabulary, describes a fundamentally different Jesus—one who began as a spirit offspring, whose body was begotten through physical means, and whose atoning work is understood in categories that depart from biblical patterns. Acknowledging these differences is not an act of hostility but of clarity. Genuine dialogue requires honest recognition of where traditions agree and where they differ. The Christological divide between Latter-day Saint theology and orthodox Christianity is wide and deep, touching the very heart of what it means to confess that Jesus Christ is Lord.

For these reasons, many scholars and church bodies have concluded that LDS theology, despite its claim to be Christian, articulates a different faith than that which the apostles delivered and the church has confessed across two millennia. This conclusion is not reached lightly, nor with animus toward Latter-day Saints as persons, but from a commitment to the integrity of biblical revelation and the theological heritage that flows from it. The question of Christ’s identity is not one among many theological questions; it is the central question upon which everything else depends. As Jesus himself asked his disciples, “Who do you say that I am?” (Matthew 16:15). The answer to that question determines not only the boundaries of Christian faith but the very hope of salvation itself.