Official LDS Positions, Critical Analysis, and the Utah Lighthouse Ministry Critique

A Scholarly Journalistic Analysis

I. Introduction: Understanding the Pearl of Great Price

The Pearl of Great Price stands as one of the four canonical “standard works” of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, alongside the Bible, the Book of Mormon, and the Doctrine and Covenants. Its name derives from the Parable of the Pearl in Matthew 13:45-46, where Jesus compares the Kingdom of Heaven to a merchant who finds a pearl of such great value that he sells everything he owns to acquire it. For Latter-day Saints, this scripture volume represents precisely such a treasure—a collection of revelations, translations, and historical narratives that they believe illuminate essential truths about God, creation, humanity’s purpose, and the restoration of the gospel.

First published in 1851 by Apostle Franklin D. Richards while serving as president of the British Mission, the Pearl of Great Price was compiled to provide Latter-day Saints in the British Isles with access to select writings of Joseph Smith that were not readily available outside the United States. As Richards stated in the Millennial Star, he hoped this collection would be “a source of much instruction and edification to many thousands of the Saints, who will, by an acquaintance with its precious contents, be more abundantly qualified to set forth and defend the principles of our Holy Faith before all men.”

The Pearl of Great Price was officially canonized on October 10, 1880, by vote at a general conference of the Church. Since that time, its contents have undergone several revisions. In 1878, portions of the Book of Moses not contained in the first edition were added. In 1902, certain parts that duplicated material published in the Doctrine and Covenants were removed. Most recently, in 1976, two items of revelation were added, only to be removed in 1979 and placed in the Doctrine and Covenants as sections 137 and 138.

The present edition of the Pearl of Great Price comprises five distinct sections: the Book of Moses (selections from Joseph Smith’s inspired revision of the Bible), the Book of Abraham (purportedly translated from ancient Egyptian papyri), Joseph Smith—Matthew (an excerpt from Smith’s revision of Matthew chapter 24), Joseph Smith—History (an autobiographical account of Joseph Smith’s early visions and the founding of the LDS Church), and the Articles of Faith (a thirteen-point summary of LDS beliefs).

This analysis examines the Pearl of Great Price from multiple perspectives: the official position of the LDS Church regarding its authority and contents, the detailed critique offered by the Utah Lighthouse Ministry in their publication “Flaws in the Pearl of Great Price,” scholarly assessments from Egyptologists and historians, and the broader questions these examinations raise about the document’s authenticity and theological implications. The goal is not to persuade readers toward any particular conclusion, but to present the evidence comprehensively so that individuals may draw their own informed judgments.

The Pearl of Great Price contains documents that have had a large impact on the beliefs, teachings, and theology of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. For example, it provided a basis in text for the practice of gathering, a passible (capable of suffering) God, premortal existence, and—most controversially—a text that was historically used to justify a ban on Black Latter-day Saints participating in temple and priesthood rituals until 1978.

The Racial Implications

The Book of Abraham has been particularly controversial due to passages that were used to justify the LDS Church’s priesthood and temple restrictions on individuals of African descent. Abraham 1:21-27 describes the curse of Ham and Canaan and their descendants being denied the priesthood. Moses 7:22 in the Pearl of Great Price states that “the seed of Cain were black.” When combined, these passages were cited by LDS leaders from the 1840s through 1978 to justify prohibiting Black members from receiving the priesthood or participating in temple ordinances.

In April 1836, within months of translating portions of the Book of Abraham, Joseph Smith himself taught regarding Genesis 9:25-27, “it remains as a lasting monument of the decree of Jehovah, to the shame and confusion of all who have cried out against the South, in consequence of their holding the sons of Ham in servitude!” This statement linked the Book of Abraham’s teachings about Pharaoh and Ham’s lineage being “cursed… as pertaining to the Priesthood” (Abraham 1:26) with the contemporary defense of American slavery.

In 2013, the LDS Church released an official “Race and the Priesthood” essay stating that it “disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse” and condemns “all racism, past and present, in any form.” The modern apologetic position often argues that the relevant Latter‑day Saint passages about curses and lineage have been misunderstood, claiming that they refer primarily to priesthood lines and family order rather than to permanent racial inferiority. However, this stands in stark contrast to the explicit teaching of early LDS leaders, especially Brigham Young, who identified the “mark of Cain” as “the flat nose and black skin” and taught that Black people were the cursed descendants of Cain, divinely barred from the priesthood until all other lineages had first received it.

In an 1859 Tabernacle sermon, for example, Young described some “classes of the human family” as “black, uncouth, uncomely, disagreeable,” and directly tied their “black skin” to God’s mark on Cain, using this to justify the long‑term priesthood restriction on those of African descent. Subsequent LDS prophets and apostles echoed and reinforced this framework for over a century—linking Black skin to the curses of Cain and Ham, to supposed premortal unfaithfulness, and to divine withholding of priesthood and temple blessings—so that the 2013 essay’s disavowal and lineage‑only reinterpretation are seen by many critics as a retrospective effort to distance the Church from its own clear prophetic teachings, rather than a faithful representation of what earlier leaders, beginning with Brigham Young, actually meant.

Cosmological Teachings

The Book of Abraham also introduces unique cosmological teachings not found elsewhere in scripture. Abraham chapter 3 describes a hierarchical system of heavenly bodies, with the star “Kolob” described as nearest to the throne of God. The text presents a universe organized around God’s dwelling place, with time flowing differently at different cosmic locations—one day on Kolob equals a thousand years on earth.

Historian Fawn Brodie and others have argued that these cosmological ideas came from Thomas Dick’s popular 1823 book “A Philosophy of a Future State,” which similarly discusses grades of “intelligences” created by God who eternally progress, and a system of astronomy with God’s throne at the very center. Sidney Rigdon quoted from Dick’s book in 1836, Oliver Cowdery published passages from it in the church newspaper, and Joseph Smith himself donated his copy to the Nauvoo library. While some LDS historians argue the direct link to Dick is tenuous, critics maintain that the Book of Abraham’s cosmology reflects nineteenth-century pseudo-scientific speculation rather than ancient astronomical knowledge.

II. The Official LDS Position

A. Scriptural Authority and Divine Origin

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints affirms the Pearl of Great Price as canonized scripture, holding it to be divinely inspired and authoritative for doctrine, faith, and practice. According to the Church’s official introduction to the Pearl of Great Price, it is “a selection of choice materials touching many significant aspects of the faith and doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. These items were produced by Joseph Smith and were published in the Church periodicals of his day.”

The LDS Church regards the Book of Moses as a divinely inspired revision of the biblical book of Genesis, restoring truths that were allegedly lost through centuries of transmission and corruption. In the 1965 Commentary on the Pearl of Great Price by George Reynolds and Janne M. Sjodahl, the authors assert that the Book of Moses presents the creation account “unimpaired or unmarred by the incidents of time,” in contrast to the biblical Genesis, which they describe as “effaced by the wisdom and carelessness of men.”

Mormon Apostle Bruce R. McConkie emphasized that Joseph Smith’s Inspired Version of the Bible (from which the Book of Moses derives) was given “at the command of the Lord and while acting under the spirit of revelation.” McConkie declared that “the marvelous flood of light and knowledge revealed through the Inspired Version of the Bible is one of the great evidences of the divine mission of Joseph Smith.”

B. The Book of Moses: Restoring the Original Record

The Book of Moses begins with the “Visions of Moses,” a prologue to the creation narrative, and continues with material corresponding to Smith’s revision of the first six chapters of Genesis. It also includes two chapters of “extracts from the prophecy of Enoch” not found in the biblical text. According to the Joseph Smith Papers project, Smith “dictated a revelation regarding many important figures from the Old Testament” beginning in June 1830, containing “the words of God which he spake unto Moses, including teachings about the Creation and its purpose, the premortal existence, the Fall of Adam and Eve, and the introduction of the gospel to Adam and Eve and their descendants.”

The LDS Church teaches that the Book of Moses restores essential truths about the creation, including the premortal existence of souls, the council in heaven, Satan’s rebellion, and the plan of salvation. These teachings form the foundation for distinctive LDS doctrines not found in traditional Christianity.

C. The Book of Abraham: Ancient Scripture Restored

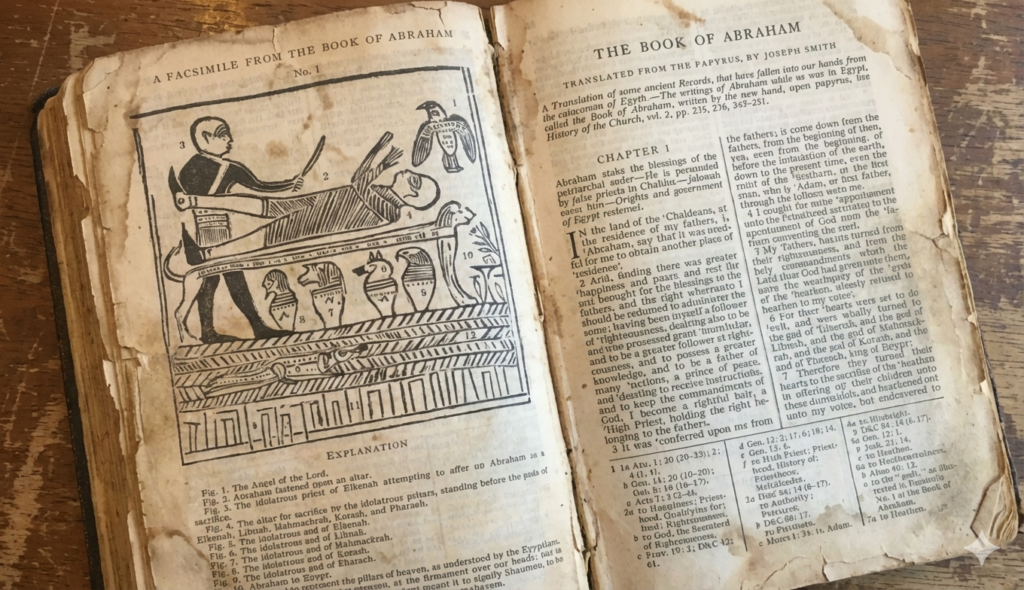

The Book of Abraham occupies a particularly significant—and controversial—place within the Pearl of Great Price. According to Joseph Smith’s own statement, published in the Times and Seasons in 1842, the book is “a translation of some ancient records… purporting to be the writings of Abraham, while he was in Egypt, called the Book of Abraham, written by his own hand, upon papyrus.”

The history of how Smith obtained the papyri is well documented. In July 1835, Michael Chandler, an antiquities dealer, visited Kirtland, Ohio, with Egyptian papyri and mummies that had been discovered in Thebes. Smith examined the scrolls and declared that they contained the writings of Abraham and Joseph. The papyri were purchased, and Smith began what he termed a “translation” of the texts. The resulting Book of Abraham was published serially in Times and Seasons in 1842, together with facsimiles of drawings found on the papyri.

The Book of Abraham introduces several doctrines that are distinctive to Latter-day Saint theology, including: the concept of God organizing eternal, pre-existing elements to create the universe rather than creating ex nihilo (out of nothing); the premortal existence of spirits; the plurality of gods; a detailed cosmology describing celestial bodies and their relationship to God’s throne; and passages that were historically used to justify the priesthood and temple restrictions placed on individuals of African descent until 1978.

D. Joseph Smith—History: The Founding Narrative

Joseph Smith—History provides the Church’s canonical account of the founding events of the Restoration, including Smith’s First Vision (in which he claimed to have seen God the Father and Jesus Christ), the visitation of the angel Moroni, the discovery and translation of the Book of Mormon, and the restoration of the priesthood. This narrative forms the foundation of LDS identity and the basis for the Church’s claims to be the restored Church of Jesus Christ.

The LDS Church presents this account as historically accurate and divinely inspired. The Joseph Smith Papers project notes that Smith began writing his official history in 1838, and the narrative was “extended by scribes and church historians until it covered Joseph Smith’s entire life.”

III. Summary of “Flaws in the Pearl of Great Price”

A. Overview of the Utah Lighthouse Ministry Critique

The Utah Lighthouse Ministry, founded by Jerald and Sandra Tanner, has produced extensive research examining LDS scripture and history from a critical evangelical Christian perspective. Their publication “Flaws in the Pearl of Great Price” (PDF attached) offers a detailed examination of the textual, historical, and theological problems they identify within this LDS standard work. Originally appearing in The Salt Lake City Messenger (Issue No. 78, June 1991) and subsequently expanded into book form, this critique has become one of the most comprehensive non-LDS examinations of the Pearl of Great Price.

The Tanners’ analysis focuses on several key areas: the extensive textual changes made to the Pearl of Great Price since its original publication, the presence of New Testament language in texts purportedly dating to ancient times, the identification of the Book of Abraham papyri as Egyptian funerary documents unrelated to Abraham, and the broader implications these findings have for Joseph Smith’s claims to prophetic authority.

B. “Drastically Changed”: Textual Revisions to the Book of Moses

One of the central arguments in the UTLM critique concerns the significant changes made to the Pearl of Great Price text since its original 1851 publication. The Tanners document that the most extensive revisions occurred in 1878, under the editorship of Orson Pratt, who produced what James R. Harris (writing his M.A. thesis at Brigham Young University in 1958) acknowledged was a version “more drastically changed than any previous publication by a member of the Church.”

“From the standpoint of omissions and additions of words, the American Edition is the most spectacular rendition… Some of the words added to the American edition had impressive doctrinal implications.” — James R. Harris, BYU M.A. Thesis, 1958

The context of these changes is significant. After Joseph Smith’s death, his widow Emma retained the original manuscripts of the Inspired Version of the Bible. Eventually, she turned them over to the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (now the Community of Christ), which the Utah-based LDS Church considered an “apostate” organization. When the RLDS Church published the Inspired Version in 1867, it became apparent that there were serious discrepancies between their publication and the chapters the LDS Church had published in the 1851 Pearl of Great Price.

According to the Tanners, Brigham Young regarded the RLDS publication as “spurious,” yet after Young died in 1877, the 1878 edition of the Pearl of Great Price was changed to agree with the RLDS publication. Harris acknowledged that “every major change in the American edition appears in identical form in the Inspired Revision.” The Tanners argue this demonstrates that “they felt the ‘apostate’ Reorganized Church had a more accurate version of the scriptures than they did!”

C. Joseph Smith’s Revision Process: “As Many as Three Times”

The UTLM critique cites RLDS Church Historian Richard P. Howard, who had access to the original manuscripts of the Inspired Version. Howard’s examination revealed a translation process quite different from what one might expect of divine revelation:

“Many texts reveal that the process was not some kind of automatic verbal or visual revelatory experience on the part of Joseph Smith. He often caused a text to be written in one form and later reworded his initial revision. The manuscripts in some cases show a considerable time lapse between such reconsiderations…” — Richard P. Howard, Restoration Scriptures

Howard further noted that the manuscripts indicate “rather clearly that Joseph Smith, Jr., by his continued practice of revising his earlier texts ‘as many as three times,’ demonstrates that he did not believe that at any of those points of rerevision he had dictated a perfectly inerrant text by the power or voice of God.” The Tanners cite this as evidence that Smith “was tampering with the Scriptures according to his own imagination” rather than receiving divine revelation.

D. New Testament Anachronisms in the Book of Moses

A significant portion of the UTLM critique addresses the presence of New Testament language and concepts within the Book of Moses—texts that purport to date from the time of Moses (approximately 1400-1200 BCE) but contain extensive parallels to Christian scriptures written over a millennium later. The Tanners document over 150 such parallels between the New Testament and the Book of Moses.

A detailed example is Moses 6:52, which they argue contains quotations from multiple New Testament passages. The verse speaks of baptism “in the name of mine Only Begotten Son, who is full of grace and truth, which is Jesus Christ, the only name which shall be given under heaven, whereby salvation shall come unto the children of men, ye shall receive the gift of the Holy Ghost.” The Tanners identify parallels to Acts 2:38 (“be baptized,” and “receive the gift of the Holy Ghost”), John 1:14 (“only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth”), 1 Corinthians 3:11 (“which is Jesus Christ”), Acts 4:12 (“none other name under heaven”), and John 16:23 (“whatsoever ye shall ask… he will give it you”).

The Tanners argue that “the problem with regard to the Book of Mormon, however, is that it purports to contain the words of ancient Nephites making extensive quotations from works that were not even in existence at that time.” The same criticism applies to the Book of Moses, where Christian terminology and concepts appear centuries before Christ. RLDS Church Historian Richard Howard concluded that “the content of all three of the documents… reflects the nineteenth century theological terminology of the prophet Joseph Smith” and “represents Joseph Smith’s studied theological commentary on the King James Version.”

E. The Book of Abraham: Egyptian Papyri Identified

The most devastating section of the UTLM critique addresses the Book of Abraham. For many years, Joseph Smith’s collection of papyri was presumed lost—possibly destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871—and there was no way to independently verify his translation. This changed dramatically in 1967.

On November 27, 1967, the Church-owned Deseret News announced that Joseph Smith’s papyri collection had been rediscovered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The article noted that “Included in the papyri is a manuscript identified as the original document from which Joseph Smith had copied the drawing which he called ‘Facsimile No. 1’ and published with the Book of Abraham.”

“The importance of this find cannot be overemphasized; it, in fact, made it possible to put Joseph Smith’s ability as a translator of ancient Egyptian writing to an absolute test.” — Jerald & Sandra Tanner, Flaws in the Pearl of Great Price

The Tanners report that within six months of the Metropolitan Museum transferring the papyri to the LDS Church, “the Book of Abraham had been proven untrue.” The identification was made possible by comparing the papyri with Joseph Smith’s Egyptian Alphabet and Grammar—handwritten documents by Smith’s scribes that the Tanners had photographically reproduced in 1966.

Noted Egyptologists Richard A. Parker and Klaus Baer translated the papyrus fragment and found that it was “in reality the Egyptian Book of Breathings.” This identification has been confirmed by multiple Egyptologists, including—significantly—LDS apologist Hugh Nibley, who made his own translation of the text. The Book of Breathings is a common Egyptian funerary text, “filled with magical practices and the names of Egyptian gods and goddesses. It has absolutely nothing to do with either Abraham or his religion.”

IV. Scholarly Assessments of the Book of Abraham

A. Egyptological Consensus

The scholarly examination of the Book of Abraham papyri represents one of the clearest cases where religious claims can be tested against academic expertise. Since the rediscovery of the papyri in 1967, translations have been published by both Mormon and non-Mormon scholars, including Michael D. Rhodes (BYU), John Gee (BYU), and Robert K. Ritner (University of Chicago).

The consensus among Egyptologists is unambiguous. Robert K. Ritner, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Chicago, concluded in 2014 that the source of the Book of Abraham “is the ‘Breathing Permit of Hôr,’ misunderstood and mistranslated by Joseph Smith.” He later stated that the Book of Abraham is now “confirmed as a perhaps well-meaning, but erroneous invention by Joseph Smith,” while acknowledging that “despite its inauthenticity as a genuine historical narrative, the Book of Abraham remains a valuable witness to early American religious history.”

The transliterated text from the recovered papyri and facsimiles contains no direct references—either historical or textual—to Abraham at all. Edward Ashment notes, “The sign that Smith identified with Abraham… is nothing more than the hieratic version of… a ‘w’ in Egyptian. It has no phonetic or semantic relationship to [Smith’s] ‘Ah-broam.’” The patriarch’s name does not appear anywhere on the papyri or facsimiles.

B. Dating the Papyri

Scholars have dated the Joseph Smith Papyri to the late Ptolemaic period, approximately 150 BCE—roughly 1,500 years after Abraham’s supposed lifetime. BYU scholar Michael Rhodes summarized the content: “The Hor Book of Breathings is a part of eleven papyri fragments… Joseph Smith Papyri I, X, and XI are from the Book of Breathings belonging to Hor (Hr), the son of Usirwer.” This dating, combined with the presence of apparent anachronisms within the Book of Abraham itself, contradicts Smith’s claims that the papyri featured “the handwriting of Abraham” written “by his own hand.”

C. The Facsimile Interpretations

Joseph Smith provided detailed explanations of three facsimiles (illustrations) published with the Book of Abraham. According to Smith, Facsimile No. 1 depicts Abraham bound to a sacrificial altar with an idolatrous priest looming over him with a knife. Facsimile No. 2 is described as a representation of celestial objects and “the grand key-words of the holy priesthood.” Facsimile No. 3 purportedly portrays Abraham in the court of Pharaoh, “reasoning upon the principles of Astronomy.”

Egyptologists identify these facsimiles quite differently. Facsimile No. 1 is a vignette from the Book of Breathings showing the deceased priest Hôr on an embalming table with the jackal-headed god Anubis performing funerary rites. Facsimile No. 2 is a hypocephalus—a common Egyptian funerary object placed under the head of the deceased to magically protect them. Facsimile No. 3 depicts a scene from Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead, showing the deceased being presented before the god Osiris.

James H. Breasted of the University of Chicago stated: “These three facsimiles of Egyptian documents in the ‘Pearl of Great Price’ depict the most common objects in the Mortuary religion of Egypt. Joseph Smith’s interpretations of them as part of a unique revelation through Abraham, therefore, very clearly demonstrates that he was totally unacquainted with the significance of these documents and absolutely ignorant of the simplest facts of Egyptian writing and civilization.”

D. The Kirtland Egyptian Papers

The collection of manuscripts produced by Joseph Smith and his scribes while working with the papyri—now known as the Kirtland Egyptian Papers—provides additional insight into Smith’s translation method. One manuscript, titled “Grammar & Alphabet of the Egyptian Language,” contains Smith’s interpretations of Egyptian glyphs. Several pages show Egyptian characters from the papyri on the left side with purported English translations on the right.

Critics note that this correlation reveals that Smith used single Egyptian characters to derive dozens of English words. As Jerald Tanner observed, “Joseph Smith apparently translated many English words from each Egyptian character. The characters from fewer than four lines of the papyrus make up forty-nine verses of the Book of Abraham, containing more than two thousand words.” If Smith maintained this ratio throughout, “the small piece of papyrus appears to be the whole Book of Abraham!”

E. Hebrew Influences and Anachronisms

Scholars have also identified significant anachronisms within the Book of Abraham text itself. The opening chapter takes place in “the land of Ur, of Chaldea,” yet the Chaldeans did not exist as a people until the 9th century BCE—well after the purported time of Abraham. Biblical scholars place Abraham living no later than 1500 BCE, making any reference to Chaldea anachronistic by several centuries.

The Book of Abraham uses the word “Pharaoh” as the proper name of the first Egyptian king, meaning “king by royal blood.” However, the word Pharaoh initially meant “great house” and was not used as a title for a king until around 1500 BCE. Additionally, the name “Potiphar” (used in Abraham 1 for “Potiphar’s Hill”) is of Late Egyptian origin and grammatical construction, using a form that did not exist in Abraham’s supposed time period. Sumerologist Christopher Woods wrote that the name Potiphar “has no place linguistically or culturally in the toponymy of southern or northern Mesopotamia.”

Perhaps most significantly, the Book of Abraham contains numerous Hebrew words spelled using the distinctive transliteration system taught by Joshua Seixas, who instructed Joseph Smith and other LDS leaders in Hebrew in early 1836. Seixas created materials with a unique Sephardic transliteration system different from what was taught elsewhere, including distinctive pronunciations for vowels and gutturals. Scholars have documented that the creation story in the Book of Abraham and explanations of the facsimiles contain multiple Hebrew vocabulary words spelled using Seixas’s unique system—vocabulary that would not have existed in any form recognizable to ancient Abraham.

The dependence on Hebrew knowledge acquired in 1836 is particularly evident in the Book of Abraham’s translation of “Elohim” as “the Gods” (plural) rather than “God” (singular). While Smith did not conceal that Hebrew was incorporated into the text, this anachronism strongly suggests the text originated in the 1830s rather than 4,000 years earlier.

The word “Egyptus” in the Book of Abraham is claimed to be Chaldean, meaning “forbidden,” but the word is actually Greek (not Chaldean) and means “the house of the ka of Ptah,” referring to the Temple of Ptah in Memphis. It does not mean “forbidden” in any language.

V. LDS Apologetic Responses

A. The “Catalyst” Theory

In response to the identification of the papyri as common Egyptian funerary texts, LDS apologists have developed several theories to defend the Book of Abraham’s authenticity. In 2014, the LDS Church published an essay on its official website acknowledging that “Mormon and non-Mormon Egyptologists agree that the characters on the fragments do not match the translation given in the book of Abraham.”

One prominent apologetic theory attempts to sidestep the translation problem entirely by recasting the papyri as merely a “catalyst” for revelation—arguing that Smith never claimed to literally translate the Egyptian text but instead received divine inspiration while contemplating the ancient documents. This clever reframing renders the actual content of the papyri conveniently irrelevant: if Smith wasn’t really translating, then the glaring mismatch between his text and what the papyri actually say becomes a non-issue. The Church’s essay completes this deflection by shifting the burden of proof away from historical evidence altogether, suggesting the truth of the book “is ultimately found through careful study of its teachings, sincere prayer, and the confirmation of the Spirit” rather than “scholarly debate concerning the book’s translation and historicity.” In other words, when the objective evidence fails to support the claim, appeal instead to subjective spiritual experience—a standard that conveniently cannot be tested or falsified.

B. The “Missing Scroll” Theory

Another apologetic argument proposes that the recovered papyri fragments represent only a portion of Smith’s original collection, and that the actual text of the Book of Abraham came from a now-missing scroll that contained Abraham’s actual writings. Contemporary accounts do refer to “a long roll” or multiple “rolls” of papyrus, and estimates suggest the recovered fragments constitute between twenty and fifty-six percent of the original collection.

Critics counter that the Kirtland Egyptian Papers explicitly correlate specific characters from the recovered papyri with the text of the Book of Abraham, making the missing scroll theory difficult to sustain. Additionally, physical analysis of the scroll of Hôr suggests that relatively little material could be missing from that particular scroll.

C. Ancient Jewish Redaction Theory

Some LDS scholars propose that the papyri may have been created by a Jewish redactor who adapted Egyptian religious sources but imbued them with a Semitic religious context. Under this theory, while the papyri themselves are Egyptian funerary documents, they might contain “encoded” references to Abrahamic traditions that Smith was able to access through revelation.

LDS apologists attempt to bolster the Book of Abraham’s credibility by pointing to alleged parallels with various ancient documents—a Coptic encomium describing Abraham’s attempted sacrifice and rescue, along with texts by Eusebius and Pseudo-Eupolemus that mention Abraham teaching astronomy to the Egyptians. They argue these parallels suggest authentic ancient traditions preserved in Smith’s text. However, this evidence is remarkably thin. The cited parallels are often vague, tangential, or require significant interpretive stretching to connect with the Book of Abraham’s specific claims. More critically, scattered references to Abraham in ancient literature—a figure already prominent in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions—hardly constitute evidence that Smith accessed genuine ancient records. Any 19th-century author familiar with biblical and apocryphal traditions about Abraham could have produced similar thematic overlaps. The apologists’ case amounts to cherry-picking loosely related ancient references while ignoring the far more substantial evidence against authenticity: namely, that the source documents Smith claimed to translate say nothing whatsoever about Abraham.

VI. Doctrinal Contradictions Within LDS Scripture

The Utah Lighthouse Ministry has documented numerous apparent contradictions between the Pearl of Great Price (and the Doctrine and Covenants) and the Book of Mormon. Sandra Tanner notes that “the Book of Mormon is closer to traditional Bible doctrine, while the more divergent teachings that distinguish the LDS church occur in the later Doctrine and Covenants and Pearl of Great Price, creating a troubling contrast, especially since the Book of Mormon is supposed to contain the ‘fulness of the gospel.’”

A. The Nature of God

The Book of Mormon repeatedly affirms monotheism and teaches that God is a spirit. Alma 11:27-39, 44 presents an extended defense of there being “only one God.” 2 Nephi 31:21 declares “the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, which is one God.” Alma 18:26-28 and 22:8-11 describe God as “a Great Spirit.”

In contrast, the Pearl of Great Price and Doctrine and Covenants teach plural gods and a corporeal deity. D&C 121:32 speaks of “the council of the Eternal God of all other gods.” D&C 130:22 states that “The Father has a body of flesh and bones as tangible as man’s.” The Book of Abraham renders “Elohim” as “the Gods” throughout its creation account, with Abraham 4:3 reading, “And they (the Gods) said: Let there be light.”

B. Pre-existence of Souls

The Book of Mormon appears to teach that souls are created rather than pre-existent. Jacob 4:9 states that God “created all things… both things to act and things to be acted upon.” Alma 18:28, 34-36 describes God as having “created all things which are in heaven and in the earth.”

The Pearl of Great Price, however, explicitly teaches the pre-mortal existence of spirits. D&C 93:23, 29-33 states, “Man was also in the beginning with God. Intelligence, or the light of truth, was not created or made.” Abraham 3:18, 21-23 describes spirits “organized before the world was” and presents a detailed account of a pre-mortal council.

C. God and Lying

The Book of Mormon repeatedly affirms that God cannot lie. Ether 3:12 declares, “O Lord… thou art a God of truth, and canst not lie.” 2 Nephi 9:34 states, “Wo unto the liar, for he shall be thrust down to hell.”

Yet Abraham 2:22-25 in the Pearl of Great Price depicts God commanding Abraham to deceive Pharaoh about Sarah being his wife: “And it came to pass when I was come near to enter into Egypt, the Lord said unto me: Behold, Sarai, thy wife, is a very fair woman to look upon; Therefore it shall come to pass, when the Egyptians shall see her, they will say—She is his wife; and they will kill thee, but they will save her alive; therefore see that ye do on this wise: Let her say unto the Egyptians, she is thy sister, and thy soul shall live.”

D. Polygamy

The Book of Mormon condemns polygamy in strong terms. Jacob 1:15 denounces the people for seeking “to excuse themselves in committing whoredoms, because of the things which were written concerning David, and Solomon his son.” Jacob 2:24 declares, “Behold, David and Solomon truly had many wives and concubines, which thing was abominable before me, saith the Lord.” Jacob 3:5 states that the Lamanites “have not forgotten the commandment of the Lord, which was given unto our father—that they should have save it were one wife.”

D&C 132, in contrast, commands polygamy and justifies David and Solomon’s multiple wives. Verse 38-39 states: “David also received many wives and concubines, and also Solomon and Moses my servants… and in nothing did they sin save in those things which they received not of me.”

VII. Comparative Examination: Biblical and LDS Scripture

LDS apologists often point to alleged contradictions in the Bible to argue that critics apply unfair standards to LDS scripture. Organizations such as FAIR (Faithful Answers, Informed Response) maintain that biblical difficulties demonstrate the Bible cannot be considered inerrant, thus making room for additional scripture and prophetic revelation.

Christian scholars respond that alleged biblical contradictions generally fall into categories that can be resolved through careful interpretation: differences in perspective among eyewitnesses, rounding of numbers, use of figurative language, genre considerations, or minor copyist variations that do not affect doctrine. As Bill McKeever and Eric Johnson of Mormonism Research Ministry argue, “The problem with most critics of the Bible is that they usually don’t want to trust or believe its message, and therefore they do not take the time to carefully research the issue.”

Critics of LDS scripture argue that the problems with the Pearl of Great Price are of a fundamentally different nature. While alleged biblical contradictions typically involve minor details in parallel accounts, the Book of Abraham presents a verifiably false claim about the nature of its source documents. The papyri are not ancient Abrahamic writings—they are Egyptian funerary texts that have nothing to do with Abraham. This is not a matter of interpretation but of factual identification by qualified experts in a relevant academic field.

VIII. Historical Questions: The First Vision Accounts

Joseph Smith—History in the Pearl of Great Price provides the canonical account of the First Vision, in which Smith claims to have seen God the Father and Jesus Christ in 1820. However, multiple accounts of this vision exist, written at different times in Smith’s life, and critics note significant variations among them.

The earliest known account, written in Smith’s own hand in 1832, describes seeing only one personage—“the Lord”—who forgives Smith’s sins. The 1835 account describes two personages who testify of Jesus. The 1838 account (which became the canonical version) describes two separate beings, God the Father and Jesus Christ, with the Father introducing the Son.

Critics argue these variations reflect the evolution of Smith’s theology from an early monotheistic (or modalistic) view toward the later doctrine of separate divine beings. They also note that D&C 84:21-22 (received in 1832) states it is impossible to see the face of God the Father without the priesthood, yet Smith supposedly saw the Father in 1820, nine years before he claimed to receive any priesthood authority.

Additionally, researcher Wesley Walters documented that no religious revival occurred in Palmyra or Manchester in 1819-1820 as described in Smith’s account; church records, newspaper accounts, and the reminiscences of contemporary ministers indicate the revival Smith described actually occurred in 1824-25.

The historical problems extend beyond the revival timing. Smith family land records, road-tax documents, and “warning out” records indicate the family did not move from Palmyra to Manchester until 1822, creating additional timeline difficulties for the canonical First Vision account. Furthermore, D&C 84:21-22, a revelation received in 1832, states that one cannot see the face of God the Father “without the ordinances thereof, and the authority of the priesthood”—yet Smith supposedly saw the Father in 1820, nine years before he claimed to receive any priesthood authority.

Critics argue that the First Vision story “evolved” over time to accommodate Smith’s developing polytheistic theology. The 1832 account, written in Smith’s own hand, contains no reference to God the Father appearing as a separate being—only “the Lord” who forgives sins. This monotheistic or modalistic understanding gradually shifted to the later doctrine of the Godhead as three separate beings, with the canonical 1838 account providing the theological foundation for LDS teachings about the corporeal, distinct nature of the Father and the Son.

The Book of Moses and Biblical Dependence

Critics have also noted extensive dependence on the King James Version of the Bible throughout the Book of Moses. The creation account in Moses chapters 2-5 retains large portions of the exact wording from Genesis, including translation choices specific to the 1611 King James translation that would not have been present in any ancient text. The Book of Abraham similarly retains approximately 75 percent of the wording from the King James Version of Genesis chapters 1 and 2 in its creation account.

Biblical scholars who employ source criticism—the Documentary Hypothesis—note that the Genesis creation account combines material from multiple ancient sources, including the Priestly source and the Jahwist source, which were combined by later editors. The Book of Abraham in several places combines these same two documents in ways that follow the King James Version combination, indicating literary dependence on the KJV rather than on any ancient original. As David Bokovoy argues, this dependency strongly suggests the Book of Abraham originated in the nineteenth century rather than antiquity.

IX. Conclusion: Evaluating the Evidence

The Pearl of Great Price presents one of the clearest cases where religious claims can be tested against historical and scientific evidence. Unlike most religious assertions, which rest on faith and cannot be empirically verified, Joseph Smith made specific, testable claims about the Book of Abraham: that the papyri were written by Abraham himself approximately 4,000 years ago, and that Smith correctly translated their content.

The evidence from Egyptology is unambiguous: the papyri date to approximately 150 BCE (not 2000 BCE), they are common funerary texts (not unique Abrahamic writings), they contain no references to Abraham (not his autobiography), and Smith’s interpretations of the facsimiles are incorrect according to every qualified Egyptologist who has examined them.

The implications of this evidence vary depending on one’s theological commitments. For critics, it demonstrates that Joseph Smith fabricated the Book of Abraham, casting doubt on his other claimed translations and revelations. For some Latter-day Saints, the apologetic theories (catalyst, missing scroll, Jewish redaction) preserve the book’s spiritual value even if its historical claims cannot be sustained. For the LDS Church, officially, the truth of the Book of Abraham rests ultimately on spiritual witness rather than scholarly analysis.

What is clear is that the Pearl of Great Price raises fundamental questions about the nature of prophetic revelation, the relationship between faith and evidence, and how religious communities respond when their foundational texts face serious historical challenges. These questions deserve thoughtful consideration by anyone seeking to understand the origins and authority of Latter-day Saint scripture.

The Broader Implications

The problems with the Pearl of Great Price extend beyond mere academic interest. For millions of Latter-day Saints, this volume is canonized scripture—the word of God, accepted as binding and authoritative. The LDS Church officially teaches that the Book of Abraham “has been a source of inspiration and doctrine, teaching us about the creation of the world, the nature of God, and the eternal destiny of humankind.”

Yet the scholarly consensus is overwhelming: the papyri Joseph Smith claimed to translate have nothing to do with Abraham. The facsimile interpretations are demonstrably incorrect. The text contains anachronisms that place its composition firmly in the nineteenth century. The textual changes to the Book of Moses reveal a revision process inconsistent with divine dictation.

For Christians engaging in dialogue with Latter-day Saints, these issues present both an opportunity and a responsibility. An opportunity because the evidence is clear, documentable, and largely undisputed, even by LDS scholars, making the Pearl of Great Price one of the strongest cases for demonstrating problems with Joseph Smith’s claims to prophetic authority. A responsibility because the goal should never be merely to “win” an argument but to point toward the truth of the biblical gospel and the sufficiency of Jesus Christ as revealed in Scripture.

The Utah Lighthouse Ministry’s work on the Pearl of Great Price, whatever one thinks of its conclusions, has made a genuine contribution to the historical record. By documenting the textual changes, identifying the anachronisms, and presenting the Egyptological evidence in accessible form, Jerald and Sandra Tanner have enabled both Latter-day Saints and interested observers to examine the evidence for themselves.

Ultimately, individuals must make their own decisions about the implications of this evidence. Some Latter-day Saints, confronted with these facts, have concluded that Joseph Smith was not a true prophet and have left the LDS Church. Others have adopted apologetic frameworks that allow them to retain faith in the Book of Abraham as scripture even while acknowledging that the papyri are not what Smith claimed. Still others have simply chosen not to engage with the evidence at all, preferring spiritual confirmation over historical investigation.

What cannot be disputed is that the Pearl of Great Price—particularly the Book of Abraham—presents specific, testable claims about ancient documents that have failed when subjected to scholarly examination. How one responds to that failure says as much about one’s epistemology (theory of knowledge) as it does about one’s theology.

X. Addendum: Selected Questions and Answers

Question 1: The “Only Begotten” Anachronism

Why is the phrase “Only Begotten” used before the incarnation of Christ? (Moses 1:13, 16, 21)

The term “Only Begotten” in Christian theology refers specifically to the incarnation—Jesus becoming flesh through Mary. Using this term before Christ’s birth is anachronistic. LDS doctrine teaches that all spirits are God’s children, making Christ’s pre-incarnate status as “Only Begotten” logically problematic. Critics argue this reflects nineteenth-century Christian terminology inserted into supposedly ancient text. The phrase “only begotten” derives from the Greek “monogenes,” which appears in the New Testament (John 1:14, 18; 3:16, 18; 1 John 4:9), yet Moses would have had no access to this Greek terminology over a millennium before it was written.

Question 2: Adam’s Joy Over the Fall

Moses 5:10 has Adam joyful over his fallen state. Can you explain this? (Moses 5:10-11)

LDS theology uniquely teaches the Fall as necessary and ultimately beneficial—“Adam fell that men might be” (2 Nephi 2:25). This directly contradicts traditional Christian teaching that the Fall was a tragic rebellion against God, bringing death and corruption into creation. The Genesis account shows God cursing the ground and expelling Adam and Eve—hardly a cause for celebration. Orthodox Christianity teaches that death, suffering, and separation from God entered the world through Adam’s sin (Romans 5:12), making the Fall the source of humanity’s deepest problems rather than a positive event. The Pearl of Great Price presents a radically different soteriology (doctrine of salvation) than that found in traditional Christianity.

Question 3: Eve’s Inability to Bear Children Before the Fall

Eve claims she could not have children before the Fall. Is this biblical? (Moses 5:11)

Moses 5:11 has Eve declare, “Were it not for our transgression we never should have had seed.” This teaching—that procreation was impossible before the Fall—has no basis in the biblical text. Genesis 1:28 records God blessing Adam and Eve before the Fall with the command to “be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth.” This command presupposes the ability to obey it. The LDS teaching appears to be a theological innovation designed to justify viewing the Fall as necessary rather than tragic.

Question 4: The Facsimile Interpretations

The figure shown in Abraham Facsimile #1 is described as Abraham about to be sacrificed, yet is representative of an Egyptian embalming ritual. What is the history? (Abraham 1)

Facsimile 1 depicts the deceased priest Hôr on an embalming table with Anubis (jackal-headed god) performing funerary rites. The “canopic jars” beneath hold internal organs. Every qualified Egyptologist identifies this as standard Egyptian mortuary imagery from the Book of Breathings, not a sacrifice scene involving Abraham. Smith’s interpretation fails every scholarly test. The figure Smith identified as “the idolatrous priest of Elkenah attempting to offer up Abraham as a sacrifice” is actually Anubis, the Egyptian god of mummification. The “sacrifice altar” is a lion couch used in embalming. The bird above the scene is not “the angel of the Lord” but the ba (soul) of the deceased, depicted as a human-headed bird—a common element in Egyptian funerary art.

Question 5: Enoch Seeing God Face-to-Face

Moses 7:4 indicates that Enoch saw God face-to-face, yet Jesus declared that no man has seen the Father except the Son. How does the LDS church explain this? (Moses 7:4)

John 1:18 states, “No man hath seen God at any time; the only begotten Son… hath declared him.” John 6:46 affirms “Not that any man hath seen the Father, save he which is of God.” 1 Timothy 6:16 describes God as dwelling “in the light which no man can approach unto; whom no man hath seen, nor can see.” LDS theology attempts resolution through the concept of “transfiguration,” suggesting humans must be temporarily transformed to endure God’s presence. However, critics note this creates ad hoc explanations for direct biblical contradictions within LDS scripture and effectively makes the biblical statements meaningless.

Question 6: God Commanding Abraham to Lie

The Lord told Abraham to lie about Sarai. Why would a just God tell his servants to lie? (Abraham 2:22-25)

While Genesis records Abraham’s deception about Sarah, it does not present God as commanding it. The Book of Abraham adds divine sanction to the lie, with God specifically instructing Abraham to have Sarah claim to be his sister rather than his wife. This contradicts numerous scriptures declaring God cannot lie (Titus 1:2, Hebrews 6:18, Numbers 23:19) and the Book of Mormon’s own testimony that God “canst not lie” (Ether 3:12). James 1:13 states that God “cannot be tempted with evil, neither tempteth he any man.” If God commanded the deception, He would be participating in sin, which contradicts His holy nature as described throughout Scripture.

Question 7: Egyptian Human Sacrifice

The Book of Abraham describes human sacrifice “after the manner of the Egyptians.” Did Egyptians practice human sacrifice? (Abraham 1:8-11)

The Book of Abraham discusses men, women, and children being sacrificed to Egyptian gods, including “a child as a thank offering.” However, offering human sacrifices to gods was not a religious practice of the ancient Egyptians. While LDS Egyptologist Kerry Muhlestein has argued that ritual killing occurred in ancient Egypt as punishment for religious dissent, critics note that religious ritual surrounding political capital punishment is fundamentally different from the religious human sacrifices described in the Book of Abraham—such as making thank offerings of children to gods. This represents a significant historical inaccuracy.

Question 8: The Name “Abraham” Before His Name Change

Why is the patriarch called “Abraham” throughout the Book of Abraham when Genesis indicates he was originally named “Abram”?

Genesis 17:5 records God changing Abram’s name to Abraham as part of the covenant: “Neither shall thy name any more be called Abram, but thy name shall be Abraham.” The Book of Abraham, however, uses the name “Abraham” from its opening verse, even in scenes that purportedly occurred before the covenant and name change. This anachronistic use of the name suggests the author was not carefully attending to the biblical timeline.

Sources and References

Primary Sources: – The Pearl of Great Price, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints – The Joseph Smith Papers Project (josephsmithpapers.org) – Pearl of Great Price Student Manual (2018), LDS Church – Times and Seasons, Vol. III (1842) – Original publication of Book of Abraham

Critical Sources: – Tanner, Jerald & Sandra. “Flaws in the Pearl of Great Price.” Utah Lighthouse Ministry. – Tanner, Sandra. “Contradictions in LDS Scripture.” Utah Lighthouse Ministry (utlm.org) – Ritner, Robert K. “A Response to ‘Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham.’” University of Chicago. – Ritner, Robert K. “The Joseph Smith Egyptian Papyri: A Complete Edition.” Signature Books, 2013. – McKeever, Bill & Johnson, Eric. “Bible Contradictions.” Mormonism Research Ministry (mrm.org) – Walters, Wesley P. “New Light on Mormon Origins from the Palmyra Revival.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought.

Academic Sources: – Wikipedia: “Pearl of Great Price (Mormonism)” and “Criticism of the Book of Abraham” – Givens, Terryl & Hauglid, Brian. The Pearl of Greatest Price: Mormonism’s Most Controversial Scripture. Oxford University Press, 2019. – Howard, Richard P. Restoration Scriptures: A Study of Their Textual Development. 1969. – Baer, Klaus. “The Breathing Permit of Hôr: A Translation of the Apparent Source of the Book of Abraham.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 1968. – Parker, Richard A. Various translations and analyses of the Joseph Smith Papyri. Brown University. – Breasted, James H. Correspondence regarding the Book of Abraham facsimiles. University of Chicago, 1912.

LDS Apologetic Sources: – FAIR (Faithful Answers, Informed Response): fairlatterdaysaints.org – “Translation and Historicity of the Book of Abraham.” Gospel Topics Essays, LDS Church, 2014. – Nibley, Hugh. “The Message of the Joseph Smith Papyri: An Egyptian Endowment.” Deseret Book, 1975. – Gee, John. Various publications defending the Book of Abraham. Brigham Young University.

Appendix: Timeline of Key Events

1835 – Joseph Smith purchases Egyptian papyri and mummies from Michael Chandler in Kirtland, Ohio. Begins “translation” of what he claims are the writings of Abraham.

1835-1836 – Joseph Smith and scribes produce the Kirtland Egyptian Papers, including the “Grammar & Alphabet of the Egyptian Language.”

1836 – Joseph Smith studies Hebrew under Joshua Seixas. Hebrew vocabulary with Seixas’s distinctive transliteration system later appears in the Book of Abraham.

1842 – The Book of Abraham is published serially in Times and Seasons, along with three facsimiles.

1851 – Franklin D. Richards publishes the first edition of the Pearl of Great Price in Liverpool, England.

1856 – Gustav Seyffarth views the papyri at the St. Louis Museum and identifies them as Egyptian funerary documents.

1856 – Theodule Deveria at the Louvre examines copies of the facsimiles and concludes Smith’s explanations are “rambling nonsense.”

1867 – The RLDS Church publishes the Inspired Version of the Bible from original manuscripts.

1871 – The Great Chicago Fire. Portions of the papyri collection are presumed destroyed.

1878 – Orson Pratt publishes a revised edition of the Pearl of Great Price, making extensive changes to agree with the RLDS publication.

1880 – The Pearl of Great Price is officially canonized as scripture by the LDS Church.

1912 – Episcopal Bishop Franklin S. Spalding sends facsimiles to Egyptologists, who uniformly reject Smith’s interpretations.

1966 – Eleven fragments of the Joseph Smith Papyri are discovered at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

1967 – The papyri are transferred to the LDS Church. Egyptologists identify them as common funerary texts.

1968 – Klaus Baer, Richard Parker, and other Egyptologists publish translations showing the papyri are Books of Breathings and Books of the Dead, unrelated to Abraham.

2014 – The LDS Church publishes a Gospel Topics essay acknowledging that “Mormon and non-Mormon Egyptologists agree that the characters on the fragments do not match the translation given in the book of Abraham.”

This analysis was compiled from the sources listed above. Quotations from the Utah Lighthouse Ministry’s “Flaws in the Pearl of Great Price” have been incorporated with proper attribution throughout. The goal of this document is to present the evidence comprehensively and objectively, allowing readers to reach their own conclusions about the authenticity and authority of the Pearl of Great Price.