A Scholarly Analysis of the Kirtland Safety Society (1836-1838)

Introduction

The Kirtland Safety Society represents one of the most controversial and consequential episodes in early Latter Day Saint history. Established in late 1836 and failing by November 1837, this quasi-banking institution left a trail of financial devastation, shattered faith, and ecclesiastical upheaval that fundamentally altered the trajectory of the fledgling religious movement. The Society’s collapse resulted in the excommunication or disaffection of approximately one-third of Church leadership, triggered Joseph Smith’s flight from Ohio, and raised enduring questions about the intersection of prophetic authority and temporal affairs.

This analysis examines the Kirtland Safety Society from multiple perspectives, drawing upon primary sources from both institutional Latter-day Saint archives and critical historical assessments. While striving for scholarly neutrality, the historical record reveals troubling patterns of financial mismanagement, unfulfilled prophetic promises, and the consolidation of spiritual and temporal authority that concerned many early Church members. Understanding this episode requires careful attention to the broader economic context of 1830s America while also acknowledging the specific decisions and claims made by Joseph Smith and other Church leaders.

The story of Joseph Smith’s troubled entry into the world of complex, large-scale, and capital-intensive finance is best highlighted in the book, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet, by John G. Turner (PDF available). Following is a summary of Chapter 2, “The Tongues of Angels,” that details the Kirland Bank’s rise and fall:

The Rise and Fall of the Kirtland Safety Society

By winter 1836-1837, the euphoria following Kirtland’s temple dedication had evaporated, replaced by dissension over Joseph Smith’s ill-fated banking venture. Mormon Kirtland faced a common frontier problem: rising land values created wealth on paper, but the community remained desperately short on actual currency. Smith conceived the Kirtland Safety Society as a solution to relieve financially distressed church elders and provide liquidity for creditors.

The Bank’s Troubled Launch

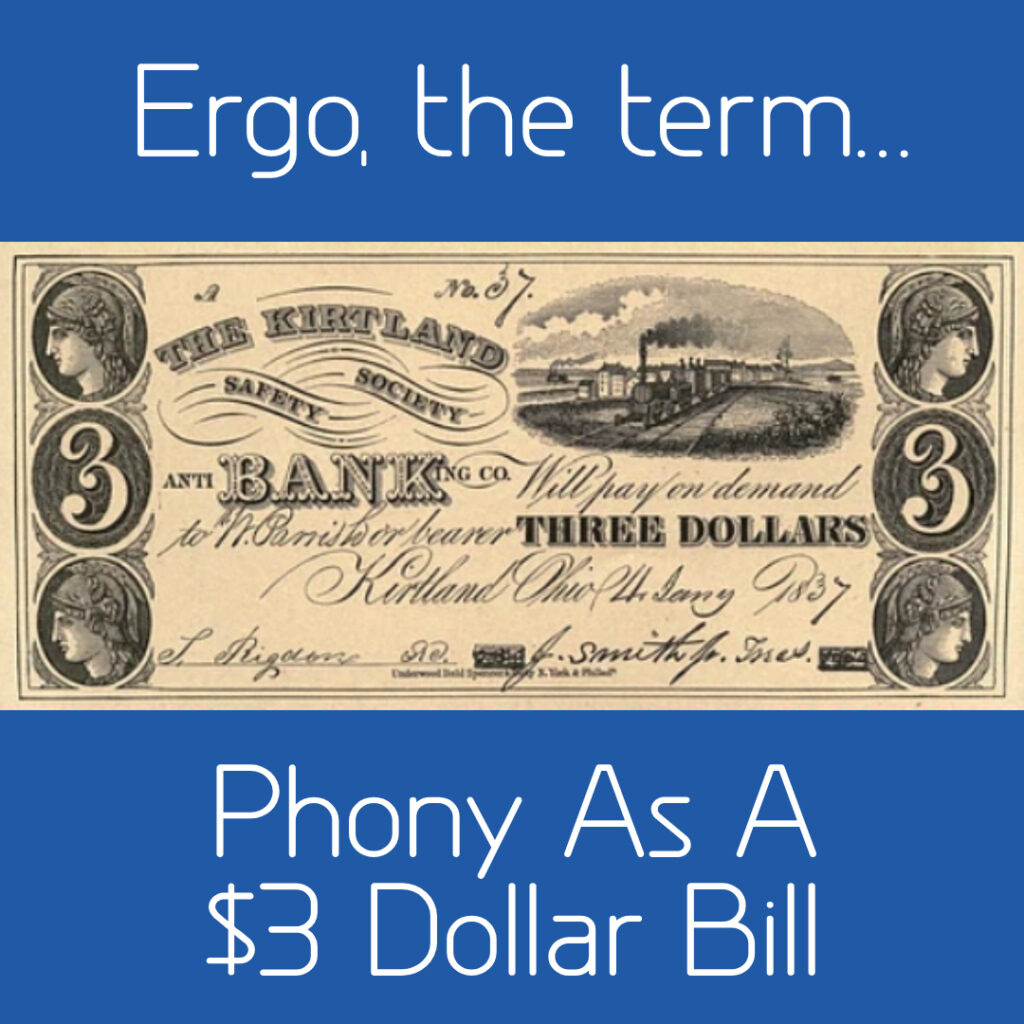

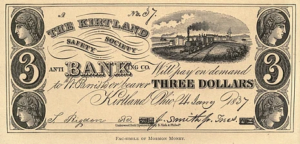

In fall 1836, Smith dispatched Oliver Cowdery to Philadelphia to purchase plates for printing banknotes and Orson Hyde to Columbus to secure a charter. The bank began selling shares before receiving approval—Brigham Young invested seven dollars for two thousand shares. When the Democratic-controlled legislature denied Hyde’s charter application, church leaders proceeded anyway, issuing notes without authorization. To avoid overtly claiming bank status, officers clumsily altered notes from “The Kirtland Safety Society Bank” to read “anti-Bank-ing Co.”—modifications that seemed to invite disaster.

Brief Prosperity

Initially, the bank generated remarkable economic activity. Willard Richards observed houses going up “almost every day,” with carpenters commanding premium prices. Men accustomed to poverty—including Smith and Young—suddenly envisioned achieving long-elusive prosperity. Richards noted that people “who were not worth a dollar one year ago are now worth their thousands and tens of thousands,” attributing the boom to the bank. He declared, “Kirtland bills are as safe as gold” in January 1837. Young prospered that winter, overseeing painting projects and purchasing property for $500.

Rapid Collapse

Regional newspapers immediately questioned “Mormon Money.” The Cleveland Gazette editorialized that the notes had “no property bound for their redemption, no coin in hand to redeem them with, and no responsible individuals whose honor or whose honesty is pledged for their payment,” concluding they “seem to rest upon a spiritual basis.” Outsiders promptly redeemed notes for specie, draining limited reserves. When a non-Mormon organized a bank run, rumors spread that redemptions had stopped, causing note values to plummet. Smith desperately sought loans and pleaded with the Saints to purchase stock with specie, but in February, the Ohio legislature officially rejected the charter application.

Leadership Crisis and Exodus

The bank’s collapse shattered confidence in Smith’s temporal leadership. While followers believed Smith understood spiritual matters, many concluded “he knew not how to manage temporal affairs.” Even Young briefly doubted Smith’s “financiering,” though he quickly repented, realizing that harboring such thoughts would ultimately undermine his confidence in Smith as God’s mouthpiece. The bank prefigured the nationwide Panic of 1837, which deepened the crisis as land values dropped and creditors swarmed Kirtland. Open battles erupted in the temple between Smith loyalists and dissenters. Smith and Sidney Rigdon were convicted of illegally issuing banknotes and fined $1,000 each. Dissidents seized control of the temple, and Smith ultimately lost Kirtland, roughly one-third of high-ranking church officers, and a sizeable portion of the membership.

I. History of the Kirtland Safety Society

Economic Context and Origins

By late 1836, the Latter Day Saint community in Kirtland, Ohio, had grown substantially since Joseph Smith’s arrival in 1831. The population of Kirtland swelled from approximately 1,000 people in 1830 to nearly 3,000 by 1836—a threefold increase driven largely by the influx of Mormon converts responding to the prophetic call to “gather to Zion.” This demographic explosion transformed the small rural village into a bustling religious center, but it also created severe economic pressures that would soon threaten the entire community’s stability.

The Church struggled to provide adequate housing, employment, and resources for this expanding population while simultaneously managing substantial debts incurred from multiple ambitious construction projects. The crown jewel of these projects was the Kirtland Temple, whose construction consumed the community’s resources and attention from 1833 to 1836. The temple project alone cost between $40,000 and $60,000—an enormous sum equivalent to between $1.3 million and $2 million in 2026 dollars. To complete this ambitious undertaking, Church leaders had mortgaged properties, solicited donations from members who often had little to give, and accumulated significant debts with local merchants and creditors who were growing increasingly impatient for repayment.

The financial strain extended far beyond temple construction. The Saints were purchasing large tracts of land for settlement, building homes, establishing businesses, and constructing other Church facilities. Many converts arrived in Kirtland with limited resources, having sold property and left employment behind to gather with the Church. This created a situation where the community needed to absorb and support new arrivals while lacking sufficient economic infrastructure to do so sustainably.

Land speculation further complicated the already precarious financial picture. According to economic historian Larry T. Wimmer’s detailed analysis, land prices in Kirtland rose dramatically from approximately $7 per acre in 1832 to a staggering $44 per acre by 1837—a more than sixfold increase in just five years. This speculative bubble was fueled partly by Mormon purchases and partly by outside speculators hoping to profit from the Saints’ continued expansion. Church leaders themselves participated heavily in land speculation, purchasing properties on credit with the expectation that continued growth and rising prices would yield substantial profits to pay off debts. However, when the bubble burst, land values collapsed precipitously to $17.50 per acre by 1839, leaving the Church and many individual members holding properties worth far less than the debts secured against them. This catastrophic loss of value would become one of several factors contributing to the financial crisis that would soon engulf the Kirtland community and force the Saints to flee Ohio entirely.

“The Kirtland Safety Society was first proposed as a bank in 1836, and eventually organized on January 2, 1837, as a joint stock company, by leaders and followers of the then-named Church of the Latter-day Saints. According to KSS’s 1837 ‘Articles of Agreement,’ it was intended to serve the financial needs of the growing Latter Day Saint community in Kirtland, Ohio.”

— Wikipedia, “Kirtland Safety Society“

Organization and Structure

The formal organization of the Kirtland Safety Society Bank took place on November 2, 1836, marking an ambitious financial venture by the Latter-day Saint leadership. Sidney Rigdon was appointed president, while Joseph Smith served as cashier—a position that carried significant operational authority over the institution’s day-to-day transactions. Oliver Cowdery was dispatched to Philadelphia to purchase engraved plates for printing currency, while Orson Hyde traveled to Columbus to secure a banking charter from the Ohio legislature. The proposed capitalization was extraordinarily ambitious—$4 million, at a time when the entire capitalization of all banks in Ohio was only $9.3 million. This figure represented nearly half of Ohio’s entire banking sector and reflected either remarkable confidence or dangerous financial overreach.

When Hyde returned from Columbus empty-handed, having failed to secure the necessary charter, the leadership made a fateful decision: they would proceed anyway, simply rebranding the operation as the “Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Company.” This semantic sleight of hand—adding “Anti-Banking” to the name and stamping it over the already-printed currency—did nothing to change the institution’s actual function as an unauthorized bank, operating in direct violation of Ohio banking laws.

“To raise more capital, Church leaders planned a bank. Like stores and mills, banks were multiplying in the 1830s. Twenty banks had been chartered in Ohio since 1830. In November 1836, Church leaders dispatched Cowdery to New York to purchase plates for printing currency, and Orson Hyde was sent to the state capitol in Columbus to apply for a charter. On November 2, the Kirtland Safety Society bank was organized and began selling stock. As usual, Joseph thought big. Capital stock was set at $4 million, though the roughly 200 stock purchasers put up only about $21,000 in cash.”

— Richard Lyman Bushman, “Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling” (2005)

The disparity between proposed capitalization and actual assets was staggering. While the Society claimed $4 million in capital, the roughly 200 stockholders contributed only about $21,000 in specie (hard currency)—less than 1% of the stated capitalization. The subscription terms were extraordinarily generous to insiders: Heber C. Kimball, for example, subscribed for $50,000 in shares for only $15 in actual payment, while Joseph Smith himself held stock valued at $66,000. The remainder of the capitalization was secured by land—a partial “land bank” arrangement that set up expectations for redeeming notes in hard money that could never realistically be met. This land consisted primarily of speculative real estate in Kirtland and surrounding areas, whose paper valuations bore little relationship to actual market value or liquidity. The fundamental unsoundness of this structure—combining minimal specie reserves, wildly inflated land valuations, and the absence of legal authority to operate—virtually guaranteed the institution’s eventual collapse.

The Charter Denial and “Anti-Banking” Reorganization

The disappointments began almost immediately after the Kirtland Safety Society’s ambitious launch. While Oliver Cowdery successfully obtained printing plates from the established firm of Underhill & Co. in New York, Orson Hyde’s mission to Columbus proved disastrous. He failed to secure a charter from the Ohio legislature, which at the time was dominated by hard-money Jacksonian Democrats deeply skeptical of paper currency and speculative banking ventures.

The political climate could not have been worse for Mormon financial aspirations. During the 1836-1837 legislative session, Ohio lawmakers adopted an extraordinarily restrictive posture toward bank charters, reflecting broader Democratic opposition to what they viewed as monopolistic privileges. The legislature rejected virtually all applications except one, denying the Mormons, along with numerous other hopeful banking enterprises. According to historian D. Paul Sampson, this represented part of a deliberate policy to limit banking expansion during a period of growing financial instability.

“In November 1836 officers of the planned bank dispatched Oliver Cowdery to obtain banknote plates from a Philadelphia engraver and Orson Hyde to secure a bank charter from the state legislature… When it became clear that the Ohio legislature would not grant a charter, the society was reorganized on 2 January 1837 as a joint-stock company under the name ‘Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Banking Company.'”

— The Joseph Smith Papers, “Introduction to the Kirtland Safety Society“

Contemporary accounts suggest initial optimism despite the charter failure. According to Wilford Woodruff’s journal, Smith prophesied that the Society would “become the greatest of all institutions on the earth” and that those who rejected its notes would “be sorry for it.” The institution opened for business with reported capital subscriptions of approximately $4 million—a staggering sum that existed largely on paper through inflated land valuations rather than actual specie reserves.

II. Motivation and Prophetic Guidance

The Claim of Divine Revelation

One of the most contentious and historically significant aspects of the Kirtland Safety Society concerns whether Joseph Smith claimed divine sanction for the enterprise. Contemporary accounts from multiple witnesses—including both loyal followers and later dissenters—establish that Smith did indeed invoke prophetic authority in promoting the institution, creating expectations among the Saints that proved disastrous when the venture collapsed.

Wilford Woodruff’s Contemporary Account

The most important primary evidence comes from Wilford Woodruff’s journal entry dated January 6, 1837—the very day the Kirtland Safety Society began operations. Woodruff, who had just been called to the First Quorum of the Seventy three days earlier, recorded attending the opening and hearing Smith speak about the institution. In his contemporary diary entry, Woodruff wrote that Smith taught, “if we would give heed to the commandments the Lord had given this morning all would be well”.

Wilford Woodruff’s diary entry from January 6, 1837:

“I also heard President Joseph Smith, Jr., declare in the presence of F. Williams, D. Whitmer, S. Smith, W. Parrish, and others in the Deposit office that HE HAD RECEIVED THAT MORNING THE WORD OF THE LORD UPON THE SUBJECT OF THE KIRTLAND SAFETY SOCIETY. He was alone in a room by himself and he had not only [heard] the voice of the Spirit upon the Subject but even an AUDIBLE VOICE. He did not tell us at that time what the Lord said upon the subject but remarked that if we would give heed to the commandments the Lord had given this morning all would be well.”

— Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, January 6, 1837

This testimony is significant for several reasons. First, it establishes that Smith claimed direct divine communication regarding the bank on the very day it began operations. Second, the audience included several prominent Church members who would later become disaffected, in part due to the bank’s failure. Third, the conditional nature of Smith’s statement—“if we would give heed to the commandments”—would later provide rhetorical cover when the enterprise collapsed.

The critical phrase “the Lord had given this morning” indicates that Smith claimed to have received divine communication about the Society that very day. Woodruff further recorded that Smith prophesied the institution “shall become the greatest of all institutions on earth” if the Saints remained faithful. This wasn’t a casual business prediction—it was presented as conditional prophetic assurance tied directly to commandments allegedly received from God.

The timing is crucial: Smith made these statements on the opening day of business, after the charter had already been denied and the institution had been hastily reorganized as a quasi-bank. Rather than acknowledging the legislative rejection as a setback, Smith framed the launch in explicitly religious terms, invoking recent divine revelation to build confidence among potential investors and note-holders.

The contrast between Smith’s claimed revelatory powers and his apparent inability to foresee the bank’s catastrophic failure raises fundamental questions about his prophetic discernment. This is the same individual who claimed to have received approximately 270,000 words of divine revelation for the Book of Mormon through direct translation by “the gift and power of God,” yet apparently could not discern through prophecy the proper procedures for establishing a viable banking operation, the futility of launching during an impending financial panic, or whether the charter application would succeed. Throughout his leadership, similar patterns emerged—elaborate revelations on doctrinal matters contrasted with administrative decisions that led to disastrous temporal consequences, suggesting a selective prophetic capacity that functioned more reliably for theological pronouncements than practical guidance.

Cyrus Smalling’s Testimony About “Aaron’s Rod”

Additional evidence comes from Cyrus Smalling, a Kirtland resident who was present during the Society’s operations. In a detailed letter written in March 1841 and later published in E.G. Lee’s The Mormons, or Knavery Exposed, Smalling provided a damning account of Smith’s rhetoric. He testified:

“I have listened to [the Prophet] with feelings of no ordinary kind when he declared that the audible voice of God instructed him to establish a Banking-Anti-Banking Institution, which, like Aaron’s rod, should swallow up all other Banks…and grow and flourish and spread from the rivers to the ends of the earth, and survive when all others should be laid in ruins.”

The Aaron’s rod metaphor is particularly significant. In Exodus 7:12, Aaron’s rod miraculously swallows the rods of Pharaoh’s magicians, demonstrating divine power over human opposition. By invoking this biblical imagery, Smith was explicitly claiming supernatural destiny for the institution—that it would supernaturally triumph over competing banks through God’s intervention. Smalling’s account indicates Smith claimed the “audible voice of God” had instructed him to establish the institution, going beyond mere inspiration to claim direct divine commandment.

The Audience: Prominent Members Who Later Apostatized

The significance of these prophetic claims is amplified by the composition of Smith’s audience, which included several prominent Church members who would soon become disillusioned. Present at these meetings were Warren Parrish (the Society’s secretary, signatory, and teller), John F. Boynton (a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles), Luke Johnson (another Apostle), and Martin Harris (one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon).

These men initially believed Smith’s assurances. John F. Boynton later explained that his difficulties with the Church resulted from “the failure of the bank,” which he had understood “was instituted by the will & revelations of God, & he had been told that it would never fail.” This testimony is critical: it confirms that prominent Church leaders understood Smith to be claiming divine revelation guaranteeing the institution’s success, not merely offering a business opinion.

Similarly, Luke Johnson and John Boynton were disfellowshipped and removed from the Quorum of the Twelve on September 3, 1837, after leading dissent against Smith. The dissenters maintained a strong local following and even conducted a competing high council that excommunicated Smith and Rigdon, forcing them to flee to Missouri. Even Martin Harris, though he remained a believer in the Book of Mormon, entered a state of apostasy during this period, though he opposed the complete rejection of Mormon scripture.

The Conditional Nature and Rhetorical Cover

The conditional phrasing in Smith’s prophecy—“if we would give heed to the commandments”—proved crucial when the enterprise collapsed. This qualifier provided rhetorical escape when accusations of false prophecy emerged. Smith and his defenders could argue that the failure resulted not from prophetic error but from the Saints’ unfaithfulness and disobedience to divine commandments.

This pattern of conditional prophecy was not unique to the Kirtland bank. It allowed Smith to maintain prophetic authority even when predictions failed to materialize by attributing the failure to human unfaithfulness rather than divine miscommunication. As historian Roger Launius observed, the Kirtland apostasy represented one of the most severe tests of Smith’s prophetic claims, precisely because so many members had understood the bank to be divinely instituted.

Stephen Burnett’s Disillusionment

The connection between the bank’s divine claims and subsequent apostasy is further documented in Stephen Burnett’s April 15, 1838, letter to Lyman E. Johnson. Burnett, who had joined the Church in 1830 and been ordained a High Priest in 1831, became thoroughly disillusioned after the Kirtland crisis. His letter indicates that many Kirtland Saints specifically felt betrayed because they had been told the institution was established by revelation, distinguishing its failure from ordinary business ventures during the Panic of 1837.

Parley P. Pratt’s Temporary Apostasy

Even Parley P. Pratt, one of the most prominent and eventually loyal apostles, was temporarily caught up in the apostasy crisis. Upon returning from a Canadian mission in 1837, Pratt found the dissension “well under way” and left a “candid account” of his temporary involvement in questioning Smith’s leadership. Though Pratt and his brother Orson would later seek forgiveness from Joseph in July 1837 and be reconciled, their momentary wavering demonstrates how widespread the crisis became.

The Salem Treasure Expedition

The financial pressures that led to the bank’s creation also prompted another remarkable episode in the summer of 1836. A church member named Burgess claimed knowledge of hidden treasure in Salem, Massachusetts. Desperate for funds, Joseph Smith, Sidney Rigdon, Hyrum Smith, and Oliver Cowdery traveled to Salem in August 1836 seeking this treasure. On August 6, Smith dictated what is now Doctrine and Covenants Section 111:

“I, the Lord your God, am not displeased with your coming this journey, notwithstanding your follies. I have much treasure in this city for you, for the benefit of Zion… And it shall come to pass in due time that I will give this city into your hands, that you shall have power over it… and its wealth pertaining to gold and silver shall be yours. Concern not yourselves about your debts, for I will give you power to pay them.”

— Doctrine and Covenants 111:1-5

No treasure was ever found. Salem was never “given into their hands.” The gold and silver promised never materialized. Smith died still heavily indebted. LDS historians have attempted to reinterpret “treasure” as referring to converts gained in later missionary efforts, but the plain language of the revelation—“gold and silver shall be yours”—clearly indicates financial treasure. This failed prophecy preceded and helped contextualize the bank venture that followed.

Documentation of Joseph Smith’s Debts at Death:

1. Bankruptcy in 1842:

Joseph Smith filed for bankruptcy in April 1842, discharging debts totaling $73,066.38 (equivalent to approximately $2.5 million in today’s dollars). This bankruptcy was made possible by a brief window when Congress enacted a lenient bankruptcy law, which was rescinded months later after $440 million in liabilities nationwide were wiped clean for only $44 million in assets. The bankruptcy proceedings were documented by LDS scholars Dallin H. Oaks (later an Apostle and current First Counselor in the First Presidency) and Joseph I. Bentley in their article “Joseph Smith and Legal Process: In the Wake of the Steamboat Nauvoo”.

2. Accumulation of New Debts:

By Joseph Smith’s own account, he owed approximately $70,000 again by the time he was killed just two years later in June 1844 (equivalent to over $1.84 million in 2010 dollars). This means that within two years of discharging over $73,000 in debts through bankruptcy, Smith had accumulated nearly the same amount in new obligations.

3. Estate Settlement Complications:

When Joseph Smith died in June 1844, his financial situation was extraordinarily complex. The official LDS Church history topic “Settlement of Joseph Smith’s Estate” acknowledges: “Joseph Smith’s untimely death in 1844 interrupted the bankruptcy proceedings. Joseph’s widow, Emma Smith, felt immediate pressure from creditors to pay Joseph’s debts.”

Joseph died without a will, and under Illinois law, his property would be divided among his widow and children after payment of creditors. However, administrators determined that “the total claims of Joseph’s creditors were about three times greater than the value of the property he owned, so Emma and the children would receive nothing.”

4. Estate Value vs. Debts:

The total value of Joseph’s properties brought back into his estate was only $11,148.35. From this:

• The United States Government received $7,870.23 (for the steamship Nauvoo debt, plus court costs and interest)

• Legal fees consumed an additional $1,468.71

• Emma’s share as a widow was a mere $1,809.41

The Dialogue Journal article “The Emma Smith Lore Reconsidered” notes that Emma’s legacy was “a debt that would plague her for years.” Estate matters in Ohio and Iowa continued into the 1860s—more than 15 years after Joseph’s death.

5. Seventeen Lawsuits:

After the Kirtland Safety Society collapse, Smith was named in seventeen lawsuits with claims totaling $30,206.44 (over $1 million in modern equivalent) over debts incurred in the failure of the bank. He appointed Oliver Granger as his agent to clear up his Kirtland affairs before fleeing to Missouri.

This pattern of chronic indebtedness and financial irresponsibility stands in stark contrast to the behavior expected of a religious leader claiming divine guidance. A responsible spiritual figure concerned with the temporal welfare of his followers would exercise fiscal prudence, especially after witnessing the devastating impact of the Kirtland Safety Society’s collapse on faithful members who lost their savings. Instead, Smith demonstrated a reckless pattern: discharging $73,000 in debts through bankruptcy in 1842, then immediately accumulating another $70,000 in obligations within two years, ultimately leaving his widow Emma with creditor claims three times the value of his estate and a “debt that would plague her for years.” This was not the conduct of a prophet concerned with providing for his family or protecting those who trusted him—it was the behavior of a man who repeatedly made grandiose financial commitments he had no realistic means of fulfilling, leaving others to bear the consequences of his imprudent decisions. For someone who claimed direct communication with God on matters ranging from temple architecture to dietary restrictions, his inability or unwillingness to manage basic financial responsibilities reveals either a profound disconnect between his claimed revelatory powers and practical wisdom or a cavalier disregard for the temporal suffering his financial recklessness inflicted on his family and followers.

The Theological Stakes

The invocation of divine revelation for the Kirtland Safety Society created theological stakes far beyond ordinary business risk. Members weren’t simply investing in a frontier banking venture—they were demonstrating faith in prophetic guidance. When the institution failed spectacularly within months, it raised fundamental questions about Smith’s prophetic reliability that nearly destroyed the Church in Kirtland. As one dissenter reportedly stated, “If Smith could be wrong about something he claimed God had directly commanded, what else might he be wrong about?”

The crisis demonstrates the dangerous intersection of prophetic authority and temporal affairs. By framing the bank as divinely mandated rather than a practical business decision, Smith elevated the stakes immeasurably—and suffered one of the most severe apostasy crises in early Mormon history when those divine claims appeared to fail.

III. Initial Success and Enthusiasm

Community Optimism

Despite the inauspicious circumstances of its founding, the Kirtland Safety Society initially generated considerable enthusiasm among the Saints. Joseph Smith’s prophetic endorsement, combined with the genuine need for credit facilities in the growing community, encouraged widespread participation. By the end of October 1836, the venture had attracted 36 subscribers contributing more than $4,000. The Smith family became the largest investors, collectively owning 12,800 shares.

“Joseph presented to us in some degree the plot of the city of Kirtland… as it was given him by vision. It was great marvelous & glorious. The city extended to the east, west, North, & South. Steam boats will come puffing into the city. Our goods will be conveyed upon railroads from Kirtland to many places & probably to Zion. Houses of worship would be reared unto the most high. Beautiful streets was to be made for the Saints to walk in. Kings of the earth would come to behold the glory thereof.”

— Wilford Woodruff, as quoted in Bushman, “Rough Stone Rolling“

Such grand visions helped sustain hope even as practical difficulties mounted. The combination of prophetic promise and economic aspiration created an atmosphere in which the Saints invested not just their money but their faith in the enterprise. This intertwining of spiritual and temporal concerns would prove devastating when the bank failed.

Early Operations

The Society began issuing notes on January 6, 1837. Initial reactions were cautiously optimistic. The Painesville Republican reported on January 19, 1837: “It is said they have a large amount of specie on hand and have the means of obtaining much more, if necessary. If these facts be so, its circulation in some shape would be beneficial to community.” However, this optimism proved short-lived.

IV. Smith’s Deceptive and Dishonest Maneuvering

The Problem of Undercapitalization

The fundamental problem with the Kirtland Safety Society was structural: it was grossly undercapitalized from the beginning. Historian Robert Kent Fielding’s assessment is damning:

“As it was projected, there was never the slightest chance that the Kirtland Safety Society anti-Bank-ing Company could succeed. Even though their economy was in jeopardy, it could scarcely have suffered such a devastating blow as that which they were themselves preparing to administer to it… The Safety Society proposed no modest project befitting its relative worth and ability to pay. Its organizers launched, instead, a gigantic company capitalized at four million dollars, when the entire capitalization of all the banks in the state of Ohio was only nine and one third million. Such presumption could not have escaped the notice of bankers who would have been led to examine its capital structure more closely.”

— Robert Kent Fielding, cited in Wikipedia

Fielding further noted that while members pledged themselves to redeem notes, “there was no transfer of property deeds, no power of attorney, no legal pains and penalties. To a banker, the articles fairly shouted: ‘this is a wildcat, beware!'” The disparity between $4 million in claimed capitalization and approximately $21,000 in actual specie reserves made the institution fundamentally unsound from its inception.

Allegations of Deceptive Practices

Later recollections suggested that the bank’s promoters engaged in deliberate deception to create an appearance of solvency that far exceeded the institution’s actual capital reserves. These allegations, while coming from hostile sources decades after the events, paint a troubling picture of confidence schemes designed to mislead potential investors and note-holders.

C.G. Webb’s 1886 Account

The most detailed description of alleged fraudulent practices comes from C.G. Webb, whose testimony was published in Wilhelm Wyl’s Mormon Portraits in 1886, nearly fifty years after the bank’s collapse. Webb described an elaborate scheme involving boxes marked with $1,000 denominations displayed prominently in the Kirtland Safety Society vault:

“Lining the shelves of the [Kirtland Safety Society] bank vault were many boxes, each marked $1,000. Actually these boxes were filled with ‘sand, lead, old iron, stone, and combustibles’ but each had a top layer of bright fifty-cent silver coins. Anyone suspicious of the bank’s stability was allowed to lift and count the boxes. ‘The effect of those boxes was like magic;’ said C.G. Webb. ‘They created general confidence in the solidity of the bank and that beautiful paper money went like hot cakes. For about a month, it was the best money in the country.'”

According to Webb’s account, the deception was carefully designed to withstand casual inspection. The boxes were heavy enough (due to the sand, lead, and iron filling) to feel substantial when lifted, and the visible layer of bright fifty-cent silver coins at the top created the impression that each box contained $1,000 worth of specie. Potential investors or skeptical note-holders who demanded to see proof of the bank’s reserves were apparently escorted into the vault and allowed to examine and even count these boxes, creating what Webb called a “magical” effect that generated widespread confidence in the institution’s solvency.

Source Reliability Considerations

The reliability of this account requires scrutiny. Wilhelm Wyl (the pseudonym of Wilhelm Ritter von Wymetal) was an Austrian journalist who published Mormon Portraits in 1886 as an explicitly anti-Mormon exposé. Wyl’s stated intent was to “debunk claims by and expose scandalous practices within the early Mormon church,” and his work has been characterized by some scholars as sensationalistic and polemical. The book was published by the Salt Lake Tribune Printing and Publishing Company and presented a compilation of interviews with individuals affiliated with Mormonism, many of whom had become disaffected.

However, several factors lend potential credibility to Webb’s specific account. First, the level of detail—describing the precise materials (sand, lead, old iron, stone, and combustibles) and the specific denomination of the visible coins (bright fifty-cent pieces)—suggests either direct observation or testimony from someone with insider knowledge. Second, the admission that this deception worked “for about a month” before the scheme unraveled aligns with the known timeline of the Society’s brief period of initial success in January 1837. Third, similar deceptive practices involving false displays of capital were documented at other frontier banks during this era, making the allegation plausible within the broader context of 1830s American banking fraud.

The account was published in 1886, forty-nine years after the events, raising legitimate questions about memory reliability and potential embellishment over time. Moreover, Wyl’s anti-Mormon agenda must be factored into any assessment of the accuracy of claims published in his work. Nevertheless, the account has been cited in multiple historical analyses of the Kirtland Safety Society, suggesting that historians have found sufficient corroborating evidence to consider it worthy of inclusion in the historical record, albeit with appropriate caveats.

Warren Parrish’s Fraud Accusations

Supporting evidence for deliberate deception comes from Warren Parrish, the Society’s secretary, signatory, and teller, who later became one of Joseph Smith’s most bitter critics. In a scathing letter published in the Painesville Republican on February 15, 1838, Parrish made sweeping accusations about Smith’s conduct during the Kirtland period:

“I have set by his side and penned down the translation of the Egyptian Hieroglyphicks as he claimed to receive it by direct inspiration of Heaven… For the year past their lives have been one continued scene of lying, deception, and fraud, and that too, in the name of God.”

Parrish’s allegations are particularly significant because of his position within the Society. As a teller, he would have had direct knowledge of the institution’s actual specie reserves and daily operations. His accusation of “lying, deception, and fraud” specifically connected to banking operations provides contemporary testimony (written in 1838, only months after the collapse) that fraudulent practices occurred.

However, Parrish’s testimony must also be evaluated in context. By early 1838, he had apostatized and was leading a rival church, having participated in an armed confrontation to seize control of the Kirtland Temple in August 1837. His letter was explicitly designed to discredit Smith and justify his departure from the Church. The LDS Church’s own footnote reference to Parrish’s letter acknowledges that he was presenting evidence of what he considered “improper financial dealings by the prophet”.

Notably, after Warren Parrish and Frederick G. Williams assumed control of the Kirtland Safety Society following Smith and Rigdon’s resignations in July 1837, Parrish himself was subsequently accused of “massive malfeasance during his tenure as president, including forgery and embezzlement.” These counter-accusations raise questions about whether some of the fraudulent practices Parrish described might have occurred under his own management rather than Smith’s, or whether the entire operation was compromised from the beginning.

The Broader Context of Frontier Banking Fraud

These allegations must be understood within the broader context of frontier banking practices in the 1830s. The period was notorious for “wildcat banking”—institutions established in remote locations with minimal capital reserves but substantial note circulation. Deceptive displays of capital were not uncommon among unscrupulous frontier bankers seeking to inspire confidence while operating on dangerously thin reserves.

The Ohio legislature’s strict refusal to grant bank charters during 1836-1837 stemmed partly from concerns about exactly these kinds of fraudulent practices. The legislature was dominated by hard-money Jacksonian Democrats who viewed paper currency with deep suspicion and were particularly wary of institutions operating without proper regulatory oversight.

Grandison Newell’s Hostile Actions

Additional context comes from Grandison Newell, a prominent Kirtland resident who became the Society’s most aggressive antagonist. Newell engaged in a calculated campaign to destroy the institution by buying up Kirtland Safety Society notes and then presenting them en masse for redemption in specie—a tactic designed to deplete the Society’s capital reserves.

Newell’s hostility toward the Mormons was longstanding and personal. He later filed an attempted murder charge against Joseph Smith in May 1837, alleging that Smith had ordered his assassination because Newell had “impugn[ed] the integrity of the founders of the Kirtland Safety Society.” Though Smith was acquitted of these charges at trial on June 9, 1837, the incident demonstrates the intense animosity surrounding the bank’s operations.

Newell subsequently served as the primary plaintiff (through his straw man, Samuel Rounds) in the only lawsuit successfully prosecuted against Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon for illegal banking. Newell reportedly paid Rounds $100 to bring the case under the Act of 1816, which had actually been suspended by the Act of 1824 during the period when the Society operated. Nevertheless, Smith and Rigdon were found guilty and fined $1,000 each in October 1837.

Newell’s vendetta continued for decades after Smith’s death. In 1860, Newell revived the judgment and manipulated probate proceedings to acquire title to the Kirtland Temple, using his own grandson-in-law as executor of Smith’s estate more than fifteen years after Smith had been killed in Carthage.

Allegations of Excessive Note Circulation

Warren Parrish also accused Smith of misrepresenting the amount of currency in circulation. According to testimony, Parrish stated that Smith, as cashier of that institution, knew that there was at least a hundred and fifty thousand dollars of bills in circulation, while claiming publicly that only ten thousand dollars of notes were outstanding. If accurate, this fifteen-fold discrepancy would represent a massive fraud against note-holders who believed the institution maintained adequate reserves relative to its outstanding obligations.

The discount and loan book for the Safety Society indicates that initial loans totaled approximately $10,000 in small denominations ($1s, $2s, and $3s) within the first week of operations. However, as the Society expanded operations through agents in communities like Akron—providing up to $30,000 in Society notes to individual agents—the total circulation likely increased dramatically.

Contemporary Newspaper Coverage

The Painesville Telegraph, which harbored strong anti-Mormon sentiments, published aggressive articles about the “dangers and alleged illegalities of the newly launched Society” almost from its inception. One article declared that Safety Society notes were:

“…thrown into circulation without any evidence or knowledge of the solvency of the issues and considered it a most reprehensible fraud on the public, since as far as we can learn there is no property Bound for the Redemption no coin on hand to redeem them with and no responsible individuals whose honor could guarantee the notes.”

The paper’s characterization of the notes as “spurious” aligned with later legal assessments. Law professors Sarah Gordon and others have concluded that “the Kirtland Safety Society Anti-Bank Company was ill considered and ill-timed and its notes were by definition fraudulent.”

The Question of Intent

The critical historical question remains whether the alleged deceptive practices—particularly the vault display described by Webb—represented intentional fraud by Joseph Smith and the original leadership, or whether they resulted from the subsequent malfeasance of Parrish and Williams after Smith’s resignation in July 1837. Smith’s public “Caution” notice, published in August 1837, explicitly warned Church members to “beware of speculators, renegadoes and gamblers, who are duping the unsuspecting and the unwary, by palming upon them, those bills, which are of no worth,” suggesting he sought to distance himself from fraudulent practices occurring under the Society’s name.

The evidence remains contested and heavily colored by the partisan nature of nearly all contemporary sources. What is undeniable is that the Kirtland Safety Society’s failure represented a financial and ecclesiastical catastrophe that led directly to mass apostasy and forced Joseph Smith to flee Kirtland for Missouri in January 1838.

Operating Without Legal Authority

The decision to operate as an “anti-banking company” after failing to obtain a charter placed the institution in a legally precarious position. While apologists have argued that such quasi-banks were common in Ohio at the time, the Painesville Telegraph noted on January 20, 1837, that it was illegal to issue bank notes without a state charter. In February 1837, Samuel D. Rounds, at the instigation of Grandison Newell, swore a writ against Smith and Rigdon for illegal banking and issuing unauthorized bank paper.

The legal proceedings eventually resulted in fines of $1,000 each against Smith and Rigdon in October 1837 for violating Ohio banking laws. While defenders argue that the prosecution was selective and motivated by anti-Mormon prejudice—larger quasi-banks operated in Ohio without prosecution—the fact remains that Smith knowingly operated an institution issuing currency without legal authorization.

The Problem of Mixed Authority

Another troubling aspect of the Kirtland Safety Society was the way it intertwined prophetic authority with financial speculation. By claiming divine sanction for the enterprise, Smith placed his followers in an impossible position: to question the bank’s wisdom was to question the prophet’s revelations. Warren Parrish later articulated this concern forcefully:

“I have been astonished to hear him [Joseph Smith] declare that we had $60,000 in specie in our vaults and $600,000 at our command, when we had not to exceed $6,000 and could not command any more; also that we had but about ten thousand dollars of our bills in circulation when he, as cashier of that institution, knew that there was at least $150,000.”

— Warren Parrish, quoted in multiple sources

Such testimony suggests not merely poor judgment but deliberate misrepresentation of the bank’s financial condition. The mixing of prophetic claims with demonstrably false financial statements created a crisis of confidence that extended beyond economics into the realm of religious authority.

V. Fall of the Enterprise

Rapid Collapse

The Kirtland Safety Society’s collapse was swift and devastating. Business began on January 2, 1837. By January 23—just three weeks later—the bank had suspended specie payments. Customers presenting notes for redemption quickly exhausted the institution’s meager liquid reserves. By February 1837, the notes were circulating at only 12.5 cents per dollar of face value, having lost half their value in mere weeks. The scheme unraveled with a speed that would make Bernie Madoff blush—at least Madoff’s Ponzi scheme lasted seventeen years before imploding; Smith’s divinely-sanctioned banking venture couldn’t survive three weeks before suspending payments to depositors who discovered the “treasure” backing their notes consisted largely of sand, lead, and prophetic assurances.

“In a simpler and more isolated society, where mutual trust was high, the scheme might have worked. In Kirtland, the bank failed within a month. Business started on January 2, 1837. Three weeks later, the bank was floundering. Skeptical (and perhaps mean-spirited) customers presented their notes for redemption, and the bank’s pitiful supply of liquid capital was exhausted within days.”

— Richard Lyman Bushman, “Rough Stone Rolling“

The Panic of 1837

The bank’s troubles were compounded by the nationwide Panic of 1837, which struck in May of that year. All banks in Ohio suspended specie payments as the financial crisis spread westward from New York. Of the 850 banks in the United States, 343 closed entirely, and 62 failed partially. However, it should be noted that the Kirtland Safety Society’s problems predated the panic by several months—the institution was already failing before the broader economic crisis struck.

Smith’s Resignation and Final Collapse

Smith transferred his holdings in June 1837 and resigned from the Society in July, convinced the institution was no longer viable. Frederick G. Williams and Warren Parrish assumed management until the final closure in November 1837. The institution closed with approximately $100,000 in unresolved debt. In August 1837, Smith publicly disavowed the Kirtland notes in the Church newspaper:

“I am disposed to say a word relative to the bills of the Kirtland Safety Society Bank. I hereby warn them to beware of speculators, renegades and gamblers, who are duping the unsuspecting and the unwary, by palming upon them, those bills, which are of no worth, here. I discountenance and disapprove of any and all such practices.”

— Joseph Smith, Messenger and Advocate, August 1837

Legal Consequences and Flight

The bank’s failure resulted in extensive legal proceedings against Smith. He was named in seventeen lawsuits with claims totaling $30,206.44. Four were settled, three were voluntarily discontinued, and ten resulted in judgments against Smith. The Church raised $38,000 in bail money at the Geauga County Court. In October 1837, Smith and Rigdon were fined $1,000 each for operating an illegal bank.

“On January 12, 1838, faced with a warrant for his arrest on a charge of illegal banking, Smith fled with Rigdon to Clay County, Missouri just ahead of an armed group intending to capture and hold Smith for trial. Smith and Rigdon were both acquainted with not only conflict and violent mobbing they experienced together in Pennsylvania and New York, but with fleeing from the law. According to Smith, they left ‘to escape mob violence, which was about to burst upon us under the color of legal process to cover the hellish designs of our enemies.'”

— Wikipedia, “Kirtland Safety Society“

The Apostasy Crisis

The bank’s failure triggered a massive crisis of faith within the Church. The volatility in prices, the pressure to collect debts, and the implication of bad faith proved too much for many believers, including some of the most prominent leaders. The scale of disaffection was staggering:

“Widespread apostasy resulted. The volatility in prices, the pressure to collect debts, the implication of bad faith were too much for some of the sturdiest believers. The stalwarts of Parley and Orson Pratt faltered for a few months. David Patten, a leading apostle, raised so many insulting questions Joseph ‘slaped him in the face & kicked him out of the yard.’ Joseph’s counselor Frederick G. Williams was alienated and removed from office. One of the Prophet’s favorites, his clerk Warren Parrish, tried to depose him. Heber C. Kimball claimed that by June 1837 not twenty men in Kirtland believed Joseph was a prophet.”

— Richard Lyman Bushman, “Rough Stone Rolling”

Half of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles accused Smith of improprieties in the banking scandal. Those excommunicated or disfellowshipped included Cyrus Smalling, Joseph Coe, Martin Harris, Luke S. Johnson, John F. Boynton, and Warren Parrish. The disaffection extended beyond leadership—approximately one-eighth of Church membership left during this period, and the Church was “rent by strife and apostasy” in Joseph and Sidney’s absence.

VI. LDS Apologist Explanations

“It Was Happening Everywhere”

A primary defense offered by LDS apologists is that the Kirtland Safety Society’s failure must be understood in the context of the Panic of 1837, when hundreds of banks failed nationwide. The official Church website presents this perspective:

“The society, along with many other banks in Ohio and across the country, failed within a year. The Panic of 1837, one of the worst economic crises in United States history, damaged many banks. After the society failed, Joseph Smith was fined for violating state banking laws. The fine and lawsuits brought against him and other principals in the society added to the burdensome debts Joseph was already carrying.”

— The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Kirtland Safety Society“

While the broader economic context is relevant, this explanation is insufficient for several reasons. First, the Kirtland Safety Society began failing in January 1837, months before the Panic struck in May. Second, the structural problems of massive undercapitalization existed from the institution’s founding. Third, and most importantly, Smith claimed divine revelation sanctioning the enterprise. If the bank was simply a well-intentioned business venture that failed along with many others, why invoke prophetic authority? And if God truly commanded its establishment, why did it fail?

“Simple Ignorance” and Good Intentions

Another common apologetic approach emphasizes that Smith and other Church leaders lacked banking experience and acted from good intentions. The FAIR LDS organization presents this view:

“Joseph probably suffered more legal repercussions than anyone from the event. There is no evidence that Joseph was ‘getting rich,’ or attempting to do so, from the bank. He paid more for his stock in the bank than 85% of the subscribers, and he put more of his own money into the bank than anyone else, save one person.”

— FAIR LDS, “Kirtland Safety Society“

This defense, while noting that Smith also lost money, fails to address several crucial issues. The Smith family collectively owned more shares than anyone else—their potential gains were commensurate with their investment. More fundamentally, claiming ignorance is difficult to reconcile with the claim of prophetic guidance. A prophet who receives audible revelation from God should presumably receive a warning when an enterprise will devastate his followers financially and spiritually.

Blaming External Enemies

Apologists also emphasize the role of external opposition, particularly from Grandison Newell, a local businessman hostile to the Mormons. Newell’s lawsuits and political maneuvering are cited as significant factors in the bank’s demise. There is truth to this—Newell did wage a proxy war against the institution. However, this explanation cannot account for the structural inadequacies of the enterprise itself.

“No Prophetic Claim Was Made”

Some apologists argue that Smith never actually claimed divine sanction for the bank, or that such claims have been exaggerated by hostile sources. The Latter-day Saints Q&A website attempts to “dispel myths” about the Society:

“Critics often claim that Joseph Smith prophesied the bank would never fail, but there is no contemporary evidence that Joseph ever made such a prophecy. The bank was a business venture, not a religious institution, and its failure has no bearing on Joseph’s calling as a prophet.”

— Latter-day Saints Q&A, “Kirtland Safety Society – Dispelling the Myths“

This defense directly contradicts Wilford Woodruff’s contemporary diary entry and Warren Parrish’s later testimony. If these witnesses are to be believed—and Woodruff was a devoted follower who became an apostle and later Church president—Smith did claim divine revelation regarding the bank on the very day it opened. The attempt to separate Smith’s “prophetic calling” from his temporal activities also fails to account for the Mormon theological framework in which spiritual and temporal authority were explicitly combined.

Blaming Warren Parrish

A final apologetic strategy involves blaming Warren Parrish for embezzlement. Smith later accused Parrish of stealing $25,000 from the institution. Heber C. Kimball claimed Parrish admitted to the crime. However, the evidence for this accusation is thin—Smith sought a warrant to search Parrish’s trunk but was denied. More importantly, the bank’s problems predated any alleged embezzlement, and the structural issues of undercapitalization cannot be blamed on any individual actor.

Beyond the standard explanations of nationwide bank failures, inexperience, external opposition, prophetic interpretation disputes, and Warren Parrish’s embezzlement, LDS official sources and apologists emphasize several interconnected financial and moral factors. The most prominent explanation centers on inadequate stockholder funding—many members who subscribed for shares never paid their initial installments or made subsequent payments, leaving the bank severely undercapitalized from its inception. This underfunding problem is framed as member disobedience and unfaithfulness to financial commitments, with Joseph Smith himself identifying speculation among Church members as a contributing factor. Official sources argue the bank’s success was conditional upon Saints giving “heed to the commandments,” suggesting the failure reflected members’ pride, greed, and disobedience rather than prophetic error.

Additional explanations focus on structural economic pressures specific to Kirtland’s situation. The collapse in land values particularly devastated the community because the bank’s capital base consisted primarily of mortgaged land, and many Saints owed money on properties purchased at inflated prices. Furthermore, the Church had assumed massive temple construction debts of $30,000-$40,000 while simultaneously funding missionary work, land purchases, and gathering efforts—all exceeding their limited financial capacity. These explanations present the collapse as resulting from the intersection of member unfaithfulness, inadequate capitalization, asset devaluation, and overextended institutional obligations rather than as a failure of prophetic leadership or divine guidance.

These explanations face significant evidentiary problems when examined against the historical record. The undercapitalization argument fails to account for the fact that Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon issued massive amounts of unbacked notes far exceeding any reasonable relationship to actual deposits or paid-in capital—a practice that would have doomed the institution regardless of stockholder payment rates. The moral failure and speculation narrative contradicts the reality that Joseph Smith himself was the primary land speculator in Kirtland, purchasing properties at inflated prices and using bank notes to finance these acquisitions. Moreover, blaming members for “disobedience” when leadership issued a reported $3 million in notes against negligible hard currency reserves essentially shifts responsibility away from the fraudulent overissuance practices that constituted the bank’s core operational model. The conditional prophecy defense—that success required member faithfulness—is undermined by contemporary accounts documenting that Joseph Smith made explicit, unconditional promises of divine establishment and guaranteed prosperity, including claims that Kirtland would become “the great commercial center of the West” and that the bank would never fail. These apologetic explanations attempt to reframe systematic financial mismanagement and unrealistic prophetic declarations as the fault of ordinary members rather than acknowledging the fundamental problems with the institution’s founding, operation, and Joseph Smith’s role in promoting it as divinely sanctioned.

VII. A Modern Parallel: The 2023 SEC Settlement

Ensign Peak Advisors and the $5 Million Fine

The patterns of financial opacity and regulatory evasion that characterized the Kirtland Safety Society have proven remarkably persistent in LDS institutional history. In February 2023, the Securities and Exchange Commission fined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its investment arm, Ensign Peak Advisors, $5 million for systematically hiding the Church’s investment holdings behind shell companies for over two decades.

“The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and a nonprofit entity that it controlled have been fined $5 million by the Securities and Exchange Commission over accusations that the religious institution failed to properly disclose its investment holdings. In an order released Tuesday, the SEC alleged that the church illicitly hid its investments and their management behind multiple shell companies from 1997 to 2019.”

— NBC News, February 21, 2023

Striking Parallels

The parallels between the Kirtland Safety Society and the Ensign Peak scandal are instructive. In both cases, Church leadership sought to conceal the true nature and extent of their financial holdings. In 1837, the bank’s promoters allegedly used boxes filled with sand topped with silver coins to create an illusion of solvency; in the modern era, Church leaders created thirteen separate shell companies to file required disclosure forms rather than one aggregated filing—deliberately obscuring the massive scale of the Church’s $32 billion (later estimated at $100 billion) investment portfolio.

“The church was concerned that disclosure of the assets in the name of the nonprofit entity, called Ensign Peak Advisors, which manages the church’s investments, would lead to negative consequences in light of the size of the church’s portfolio, the SEC said… The SEC accused the church Tuesday of going to ‘great lengths’ to avoid disclosing its investments and, in doing so, ‘depriving the commission and the investing public of accurate market information.'”

— NBC News, February 21, 2023

The Fear of Disclosure

Perhaps most tellingly, both episodes reveal an institutional concern about what transparency would reveal. In Kirtland, the bank’s promoters feared that honest disclosure of the institution’s meager specie reserves would undermine confidence. In the modern era, Church leaders feared that disclosure of the portfolio’s enormous size would lead to “negative consequences”—presumably including questions about why a church ostensibly devoted to caring for the poor had accumulated such staggering wealth.

The Wall Street Journal, which first exposed the Ensign Peak fund in 2019, noted that “For more than half a century, the Mormon Church quietly built one of the world’s largest investment funds. Almost no one outside the church knew about it.” The secrecy was deliberate and sustained over decades—a pattern that echoes the Kirtland era’s financial opacity.

Institutional Responses Then and Now

The Church’s response to the SEC settlement also mirrors patterns from the Kirtland era. In its official statement, the Church acknowledged that Ensign Peak “received and relied upon legal counsel regarding how to comply with its reporting obligations while attempting to maintain the privacy of the portfolio.” This framing—emphasizing reliance on counsel and procedural compliance while minimizing the deliberate nature of the concealment—echoes the apologetic strategies employed regarding the Kirtland Safety Society: mistakes were made, external factors were involved, and intentions were good.

The Church’s statement concluded: “We affirm our commitment to comply with the law, regret mistakes made, and now consider this matter closed.” This language of regret for “mistakes” rather than acknowledgment of deliberate deception mirrors the persistent reluctance to forthrightly address the Kirtland episode. In both cases, institutional self-interest conflicted with transparency, and transparency lost.

The Continuity of Institutional Culture

The 186-year span between the Kirtland Safety Society and the Ensign Peak scandal suggests that certain institutional patterns have remained remarkably consistent. The intertwining of religious authority and financial management, the preference for opacity over transparency, the concern that honest disclosure would create “negative consequences,” and the tendency to minimize and deflect when problems come to light—all these features of LDS institutional culture were present at Kirtland and remain visible today.

This continuity raises uncomfortable questions. If patterns established in the Church’s earliest years persist nearly two centuries later, to what extent has the institution truly learned from the Kirtland debacle? The SEC settlement suggests that the answer may be: not as much as one might hope.

VIII. Conclusion

The Kirtland Safety Society disaster exposes a fundamental problem with Joseph Smith’s claim to prophetic authority: he failed the biblical test that distinguishes true prophets from false ones. Traditional Christianity has always applied a straightforward standard from Deuteronomy 18:21-22: “How may we know the word that the Lord has not spoken?—when a prophet speaks in the name of the Lord, if the word does not come to pass or come true, that is a word that the Lord has not spoken; the prophet has spoken it presumptuously.” By this measure, Smith’s prophetic credentials collapse under scrutiny.

Smith didn’t merely make a business mistake—he presented the bank as divinely ordained relief for his financially distressed elders, claiming to act under God’s direction. He prophesied Kirtland’s future grandeur and encouraged his followers to invest their meager resources based on his spiritual authority. Willard Richards declared in January 1837 that “Kirtland bills are as safe as gold,” reflecting the confidence Smith inspired through his prophetic claims. Within weeks, those same notes became worthless paper, and within months, Smith had lost Kirtland entirely—hardly the fulfillment of divine promises about the city’s destiny.

What makes this particularly damning is Smith’s response when his prophecies failed. Rather than acknowledging error or accepting that he had spoken presumptuously, he shifted blame and maintained his prophetic status. Biblical prophets who spoke falsely in God’s name were to be executed (Deuteronomy 18:20). Smith faced no such accountability because he controlled the narrative, excommunicating dissenters and threatening those who questioned him. When Jacob Bump—who had been “the first to circulate” the bank’s notes and lost $500 in worthless Kirtland scrip—expressed anger at a church meeting, Smith loyalists like Brigham Young threatened physical violence rather than offering restitution or repentance.

Smith’s defenders argue that God allowed him to “commit an error” and that this doesn’t invalidate his prophetic office. But this fundamentally misunderstands biblical prophecy. When a prophet claims divine direction for a venture, presents it as God’s solution to his people’s suffering, and that venture becomes an “unmitigated disaster” that causes widespread financial ruin and destroys faith—this isn’t a minor human error. It’s proof that he spoke presumptuously in God’s name, which Deuteronomy explicitly identifies as the mark of a false prophet.

For those committed to Smith’s prophetic calling, the bank’s failure must be explained away through appeals to external economic conditions, persecution by enemies, the conditional nature of prophetic promises, or the separation of spiritual and temporal spheres. For critics, the episode exemplifies a pattern of prophetic overreach, financial mismanagement, and the use of religious authority for personal and institutional gain.

The dissenters of Kirtland—Warren Cowdery, Warren Parrish, David Whitmer, John Corrill, and many others—were not merely greedy speculators disappointed by financial losses. Many were intelligent, devoted believers who saw in the bank episode confirmation of concerns they had harbored for years: that Joseph Smith was claiming too much authority, that he was mixing spiritual and temporal matters inappropriately, and that he was not accepting the counsel or criticism that might have prevented disaster.

Warren Cowdery’s words from 1837 remain haunting: “Whenever a people have unlimited confidence in a civil or ecclesiastical ruler or rulers, who are but men like themselves, and begin to think they can do no wrong, they increase their tyranny and oppression, establish a principle that man, poor frail lump of mortality like themselves, is infallible.” The Kirtland Safety Society’s failure was not merely an economic catastrophe but a test of whether a religious community could hold its leader accountable. Many concluded it could not and voted with their feet.

The episode also raises profound questions about the nature of prophetic authority. If a prophet claims divine revelation regarding a temporal enterprise, and that enterprise fails catastrophically, what conclusions should followers draw? The traditional answer—that God’s promises were conditional on human faithfulness—places all blame on the followers while insulating the prophet from accountability. But such a framework makes prophetic claims essentially unfalsifiable: if the prophecy succeeds, God spoke; if it fails, the people disobeyed. This logical structure mirrors the defense mechanism employed by Scientologists when confronted with failed “tech”: the methodology is infallible, so any failure must result from the practitioner’s errors—“you did it wrong.” In both systems, the authority figure’s claims can never be disproven because failure is always attributed to the follower’s inadequacy rather than the leader’s false promises. When Joseph Smith’s bank collapsed three weeks after he prophesied it would “become the greatest of all institutions on earth,” the problem wasn’t the prophecy—it was that the Saints didn’t “give heed to the commandments” with sufficient exactness. The faithful lose their savings, the prophet retains his authority, and the cycle continues uninterrupted.

Finally, the Kirtland Safety Society illustrates the dangers of mixing religious authority with financial ventures. When prophetic sanction is claimed for business enterprises, ordinary prudential calculations become acts of faith or doubt. Questioning the wisdom of an investment becomes questioning God’s prophet. This dynamic, visible in Kirtland in 1837, would manifest repeatedly in subsequent Mormon history.

The Kirtland Bank didn’t just fail financially—it failed theologically. A true prophet of God would never have led his followers into such deception, desperation, and disaster while claiming divine sanction. Smith’s willingness to send Brigham Young across the Northeast purchasing property with worthless scrip from distant victims, “unlikely to quickly redeem them,” reveals not prophetic vision but calculated fraud. Traditional Christianity cannot recognize as a prophet someone who manipulates divine authority to perpetrate financial schemes that Scripture would condemn as bearing false witness and defrauding neighbors.

Joseph Smith may have been many things—a charismatic leader, a religious innovator, a gifted storyteller—but by the biblical standard that has guided Christianity for two millennia, the Kirtland Bank debacle proves he was no prophet of God.

Bibliography and Sources Consulted

Primary and Secondary Sources:

• Bushman, Richard Lyman. Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling. New York: Knopf, 2005.

• The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “Kirtland Safety Society.” Topics and Questions.

• The Joseph Smith Papers. “Introduction to the Kirtland Safety Society.”

• Wikipedia. “Kirtland Safety Society.”

• FAIR LDS. “The Kirtland Safety Society’s Collapse is Significant.”

• Analyzing Mormonism. “Kirtland Safety Society Bank.”

• Mormonism Research Ministry. “Putting ‘History’ Back in the LDS Church’s News Release on Historic Kirtland.”

• Exploring Mormonism. “Kirtland Timeline – Kirtland Safety Society.”

• Book of Mormonism. “A History of Joseph Smith’s Financial Malfeasance (Pt. 3).”

• Mormonism Research Ministry. “Kirtland Safety Society.”

• Latter-day Saints Q&A. “Kirtland Safety Society – Dispelling the Myths.”

• Fielding, Robert Kent. The Growth of the Mormon Church in Kirtland, Ohio. Ph.D. Diss., Indiana University, 1957.

• Hill, Marvin S., C. Keith Rooker, and Larry T. Wimmer. “The Kirtland Economy Revisited.” BYU Studies 17, no. 4 (1977).

• Woodruff, Wilford. Journal entries, 1837.

• Parrish, Warren. Painesville Republican, February 1838.