A Scholarly Examination from Inquisitive and Historical Perspectives

Introduction to the Golden Plates and Their Significance

The golden plates represent the foundational artifact claim of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), serving as the purported ancient record from which Joseph Smith translated the Book of Mormon between 1827 and 1829. According to Latter-day Saint belief, these plates contained the religious history of ancient peoples who inhabited the Americas, written in a script called “Reformed Egyptian” and compiled by ancient prophet-historians Mormon and his son Moroni around 400 CE.

As Mormon historian Richard Bushman acknowledges, the credibility of these plates has been a “troublesome item” throughout Mormon history. He observes that “For most modern readers, the plates are beyond belief, a phantasm, yet the Mormon sources accept them as fact.” This tension between faith-based acceptance and historical scrutiny forms the crux of ongoing debates about Mormon origins and the nature of religious authority in the Latter Day Saint movement.

Richard Bushman’s observations on the golden plates stem from his biographical work on Joseph Smith and related scholarly discussions. These quotes highlight the historical tension surrounding the plates’ credibility in Mormonism.

As for the unanswered questions, we’ve got more than enough to stump the average LDS missionary team—assuming, of course, they haven’t mastered quantum physics, ancient metallurgy, and angelic retrieval logistics between doorsteps.

Primary Sources

Bushman describes the plates as “the single most troublesome item in Joseph Smith’s history” in his 2005 book Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling (p. 58). He further notes: “The Mormon sources constantly refer to the single most troublesome item in Joseph Smith’s history, the gold plates on which the Book of Mormon was said to be written. For most modern readers, the plates are beyond belief, a phantasm, yet the Mormon sources accept them as fact.”

Scholarly Context

These statements appear in contexts throughout his book, (PDF), addressing Mormon origins, where Bushman contrasts faith acceptance among early believers with modern skepticism. FAIR Latter-day Saints confirms the “phantasm” quote’s attribution to Bushman (2005, p. 58).

Debate Implications

Bushman positions the plates as a pivotal challenge, dividing views on Joseph Smith as prophet or fraud, fueling apologetics and criticism. This underscores ongoing scrutiny of religious artifacts in Latter-day Saint history.

The significance of the golden plates extends far beyond their alleged physical existence. They represent a fundamental theological rupture from traditional Christianity’s understanding of how God preserves His Word. Orthodox Christianity maintains that God providentially guided the preservation of Scripture through centuries of manuscript transmission, councils of church fathers, multilingual textual traditions (Hebrew, Greek, Aramaic), and rigorous textual criticism—a process involving thousands of manuscripts, hundreds of scholars, and multiple languages that allowed independent verification at every stage.

In contrast, the Book of Mormon claims authority through a single individual’s private encounter with an angelic messenger and a translation process that not only bypassed conventional linguistic scholarship but required the destruction of all source materials. Where God allegedly preserved the Bible through proliferation (thousands of manuscript copies ensuring textual reliability), He supposedly preserved the Book of Mormon through elimination—one translator, zero manuscripts, no verification possible. This singular, unverifiable path to scriptural authority stands in stark contradiction to the biblical model: God protected His Word by scattering it across continents and centuries in multiple languages with countless witnesses, yet somehow reversed this entire methodology for the Book of Mormon by funneling everything through one man in upstate New York with a seer stone in a hat.

This departure raises profound questions about the nature of divine revelation, prophetic authority, and the transmission of sacred texts. If God’s established pattern was public, verifiable, multi-witness preservation, why would He abandon that proven method for a process that looks suspiciously like the very “private interpretation” that Scripture warns against (2 Peter 1)?

16 For we have not followed cunningly devised fables, when we made known unto you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but were eyewitnesses of his majesty.

17 For he received from God the Father honour and glory, when there came such a voice to him from the excellent glory, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.

18 And this voice which came from heaven we heard, when we were with him in the holy mount.

19 We have also a more sure word of prophecy; whereunto ye do well that ye take heed, as unto a light that shineth in a dark place, until the day dawn, and the day star arise in your hearts:

20 Knowing this first, that no prophecy of the scripture is of any private interpretation.

21 For the prophecy came not in old time by the will of man: but holy men of God spake as they were moved by the Holy Ghost.

For traditional Christians, the golden plates narrative presents theological and historical challenges that touch upon fundamental doctrines of sola scriptura, the sufficiency of Scripture, and the closed canon. The claim that an angel revealed a “new” scripture approximately 1,400 years after the apostolic age conflicts with biblical warnings against adding to divine revelation (Revelation 22:18-19, Galatians 1:8-9). Furthermore, the absence of physical evidence, the reliance on subjective spiritual witnesses, and the problematic historical claims surrounding the plates’ discovery and translation demand careful examination from both faith-based and secular perspectives.

Ligonier Ministries: What Does “Sola Scriptura” Mean?

The Reformation principle of sola Scriptura has to do with the sufficiency of Scripture as our supreme authority in all spiritual matters. Sola Scriptura simply means that all truth necessary for our salvation and spiritual life is taught either explicitly or implicitly in Scripture. It is not a claim that all truth of every kind is found in Scripture. The most ardent defender of sola Scriptura will concede, for example, that Scripture has little or nothing to say about DNA structures, microbiology, the rules of Chinese grammar, or rocket science. This or that “scientific truth,” for example, may or may not be actually true, whether or not it can be supported by Scripture—but Scripture is a “more sure Word,” standing above all other truth in its authority and certainty.

Historical Context and Background of Joseph Smith

The Second Great Awakening and Religious Fervor

Joseph Smith Jr. (1805-1844) emerged from the crucible of early 19th-century American religious enthusiasm known as the Second Great Awakening. Born in Sharon, Vermont, Smith’s family relocated to Palmyra, New York, in 1816, settling in an area that would later be dubbed the “burned-over district” due to the intensity of religious revival meetings that swept through the region like spiritual wildfire.

This period of American history was characterized by competing Christian denominations vying for converts, charismatic preachers conducting emotional camp meetings, and a general atmosphere of religious experimentation. The Smith family, like many frontier families, struggled financially and participated in the religious and cultural practices of their time, including folk magic, treasure seeking, and various forms of divination.

Treasure Digging and Folk Magic Culture

A critical yet often overlooked aspect of Joseph Smith’s background is his extensive involvement in treasure-digging activities. Historical evidence, including court records and contemporary accounts, establishes that Smith was hired by various individuals between 1822 and 1827 to locate buried treasure using seer stones—smooth rocks he claimed possessed supernatural properties that allowed him to “see” hidden objects underground.

The practice of treasure digging in early 19th-century America blended folk magic, occult beliefs, and the widespread conviction that Spanish or Native American treasures lay buried throughout the Northeast. Practitioners believed that treasures were protected by guardian spirits and could “slip” deeper into the earth if proper magical rituals were not observed. These rituals often involved specific dates (particularly equinoxes), colors (especially black), the “power of three“ (three attempts or three witnesses), and special stones or instruments.

According to Dan Vogel, a prominent historian of early Mormonism, Smith’s treasure-digging career began around 1822 and continued through his 1826 trial in Bainbridge, New York, where he was charged as a “disorderly person” for pretending to find hidden treasures through supernatural means. Court documents reveal that Smith confessed to using a seer stone to search for buried treasure, though he claimed to have recently abandoned the practice.

This magical worldview deeply influenced the golden plates narrative, as evidenced by:

- The angel Moroni’s appearance on September 21-22, 1823 (the autumnal equinox, a particularly powerful date in magical practices).

- Smith’s claim that he attempted to retrieve the plates three times in 1823 but was prevented by supernatural force.

- The requirement that Smith bring the “right person” to retrieve the plates.

- The use of seer stones to locate and later “translate” the plates.

- The concept of a guardian spirit (later identified as an angel) protecting the treasure.

The 1826 Trial: A Turning Point

The 1826 trial of Joseph Smith in South Bainbridge, New York, underscores his involvement in treasure seeking using a seer stone, just before he pivoted to claiming divine visions and the golden plates. Court documents and witness accounts reveal a mix of supporters and skeptics, with no severe penalty imposed, marking a key shift in his narrative from folk magic to prophetic claims.

There is substantial scholarly and historical evidence suggesting the 1826 trial could have been a primary catalyst for Joseph Smith’s pivot from treasure digging to prophetic claims about the golden plates.

The timing is critically important: Joseph Smith was tried in March 1826 for being a “disorderly person” and “glass looker” while working for Josiah Stowell. According to his own account, he first claimed the angel Moroni appeared to him in September 1823, but he didn’t obtain the plates until September 1827—just over a year after the trial.

John Dehlin’s analysis notes that “once he was found guilty of fraud, Joseph Smith pivoted from treasure digger to Book of Mormon translator, ‘prophet,’ and ‘seer'”. The pattern is striking: Joseph used the exact same methods (seer stone in hat) for both treasure digging and Book of Mormon translation, but reframed the narrative from commercial treasure hunting to religious revelation.

Martin Harris reported that the angel Moroni specifically commanded Joseph to “quit the company of the money-diggers” and called them “wicked men”. This directive came after Joseph’s treasure-digging activities became legally problematic.

An anonymous YouTube commenter, quoted in John Dehlin’s, “Why Joseph Smith’s Treasure Digging Causes People to Leave the Church,” Mormon Stories (Substack), July 13, 2025, observed: “His investors were not investing in him having visions to lead them to treasure. They were investing in his visionary translation of the story the treasure contained! And the translation could be turned into a book, which could be sold.”

Whether the 1826 trial was the sole impetus is debatable, but the evidence strongly supports it as a significant motivating factor for reframing his practices from commercial fraud to religious mission.

Trial Details: Joseph was examined on March 20, 1826, before Justice Albert Neely on charges of being a “disorderly person” and an impostor for pretending to find hidden treasures via a stone. Josiah Stowell testified positively, affirming Joseph’s skill in locating treasures and lost items, stating he had “the most implicit faith” in him despite failed digs due to supposed enchantments. Other witnesses, like Horace and Arad Stowell (Josiah’s relatives), were skeptical; Arad described a failed demonstration as “palpable deception.”

Family Testimony: Joseph Sr. testified that his son had worked on farms, attended school, and used the stone sparingly, declining most requests as it harmed his eyes. Church sources interpret Joseph Sr.’s remarks as hoping Joseph would use his “gift” for godly purposes rather than earthly treasure, aligning with later family encouragement toward spiritual pursuits.

Legal Outcome: The docket notes a “guilty” finding with costs of $2.68, but accounts vary: some say Joseph was discharged due to Stowell’s credible testimony, others that he escaped lightly due to his youth. Treasure seeking was prosecutable as fraud under New York law, yet Joseph faced no jail time and continued associating with Stowell.

Shift to Plates Narrative: Post-trial, Smith refocused from secular digs; his 1838 history claims annual Hill Cumorah visits from 1823–1827, but no contemporary records confirm a 1825 visit amid heavy treasure work. Historian Dan Vogel argues Smith likely set aside the plates story temporarily during this peak treasure phase (1824–1826), resuming it afterward.

Historical Analysis: LDS apologists predictably downplay the trial’s significance—characterizing it as minor with acquittal supposedly vindicating Smith’s “legitimate” folk practices—following their typical pattern of minimizing evidence critical of Joseph Smith’s history. Critics, however, view the trial as exposing Smith’s “glass-looking” as fraudulent groundwork that later evolved into Mormon origins. This episode illustrates the blurred line between 19th-century treasure culture and emerging religious claims in early Mormonism.

Examination of Controversies and Differing Narratives

The Discovery and Retrieval: Multiple Accounts

The story of how Joseph Smith obtained the golden plates exists in multiple, sometimes contradictory versions. Smith’s own accounts evolved, with significant details added, modified, or omitted across different tellings.

The 1823 Visitation: Joseph Smith’s accounts of the angel’s 1823 visits evolved, with the canonized 1838 version providing the most detailed narrative of Moroni directing him to the golden plates. Earlier records show simpler descriptions and inconsistencies in the angel’s identity, prompting debates on memory, elaboration, or harmonization in early Mormon history.

1838 Canonized Account: In Joseph Smith—History (Pearl of Great Price 1:30–54), Smith describes Moroni appearing four times on September 21–22, 1823: three times at night in his bedroom with a brilliant light and once the next day in a field. The angel, “glorious beyond description,” revealed gold plates buried in the Hill Cumorah, quoted scriptures (Malachi 3–4, Isaiah 11, Joel 2), warned of worldly opposition, and instructed Smith not to retrieve the plates until 1827 due to unpreparedness. This account, drafted 1838–1839 and canonized in 1880, emphasizes divine preparation amid Smith’s youth and family revivalism.

1832 Earliest Account: Smith’s handwritten 1832 history (Joseph Smith Papers) recounts a single nighttime vision at age 17: “an angel of the Lord” entered his room with intense light, forgave his sins, and revealed gold plates in Manchester engraved by “Moroni” (third-person reference, no self-identification). It omits multiple visits, daytime appearances, or specific quotes, focusing on forgiveness and the record’s location.

Name Evolution: Moroni vs. Nephi: The remarkable confusion surrounding even the name of the angel who allegedly launched the entire Mormon movement reveals the narrative instability plaguing Mormon attempts to document “the truth.” Early sources vaguely call the visitor simply “the angel” (1830–1835), offering no specific identification. By 1835, a revelation finally named the messenger as Moroni (D&C 27:5).

However, Joseph Smith’s own 1839 manuscript of what would become Joseph Smith—History 1:33 explicitly labels the angel “Nephi“—a designation later quietly edited to “Moroni” after Smith’s death. The confusion deepens: an 1842 Times and Seasons article (edited by Smith himself) and the 1851 first edition of the Pearl of Great Price both identified the angel as “Nephi,” only to have the name posthumously changed in subsequent editions.

This isn’t a minor detail—getting the name of the foundational angelic messenger wrong in multiple official publications spanning over a decade stretches credulity. Apologists awkwardly suggest “scribal error” or conflation with Nephi’s visions in the Book of Mormon; critics see the telltale signs of evolving mythology where details hadn’t yet crystallized. The irony is inescapable: a church claiming to restore “the fulness of truth” through divine revelation couldn’t consistently identify its own angel for the first 20+ years of its existence, requiring posthumous editorial corrections to establish what supposedly happened in 1823. If Joseph Smith himself couldn’t keep straight whether Moroni or Nephi visited him—or didn’t consider the distinction important enough to correct in publications he personally edited—it raises profound questions about the reliability of the entire golden plates narrative.

Scholarly Perspectives

Apologists argue that accounts complementarily expand details without contradiction, reflecting oral retellings. Critics like Dan Vogel note progressive enhancements, with anachronistic scripture quotes (e.g., Malachi phrasing post-1834) indicating later insertions for 1838 audiences facing Missouri persecutions. No contemporary 1823 corroboration exists beyond Smith’s word.

Implications for Reliability: These variances—number of visits, angel’s name, details—fuel debates on visionary authenticity versus folkloric development in 19th-century revivalism. They parallel First Vision account discrepancies, challenging claims of precise historical recall.

Oliver Cowdery, who served as Smith’s scribe and later became one of the Three Witnesses, published letters in 1834-1835 describing the discovery in terms strikingly similar to treasure-digging narratives. Cowdery wrote:

“On attempting to take possession of the records [gold plates] a shock was produced upon his system, by an invisible power, which deprived him in a measure, of his natural strength. He desisted for an instant, and then made another attempt, but was more sensibly shocked than before.”

This description of supernatural resistance preventing the retrieval of treasure perfectly mirrors treasure-digging lore, where guardian spirits protect buried treasures and prevent their removal unless specific magical conditions are met.

The “Right Person” Requirement: One of the most peculiar aspects of the golden plates narrative involves the requirement that Smith bring the “right person” to retrieve the plates. According to Joseph Knight Sr., a faithful early Mormon, the angel told Smith during his failed 1823 attempt:

“Joseph says, ‘when can I have it?’ The answer was the 22nd Day of September next if you Bring the right person with you. Joseph says,’ who is the right Person?’ The answer was ‘your oldest Brother.'”

However, Smith’s oldest brother, Alvin, died in November 1823, just two months after this alleged instruction. This creates a theological problem: why would an omniscient angel direct Smith to bring someone who would die before the appointed time?

The attempted 1824 retrieval, without Alvin, failed. Remarkably, five days after Smith’s failed attempt, his father, Joseph Smith Sr., published a public notice in the Wayne Sentinel regarding disturbing reports that Alvin’s body had been exhumed. The notice stated that Joseph Sr. and neighbors had dug up the grave to prove the body remained intact.

Historian Dan Vogel has noted that this explanation seems questionable—one could determine if a grave had been disturbed without fully exhuming the body. Vogel theorizes that Joseph Sr. himself may have orchestrated the exhumation, believing that Alvin’s presence (even his corpse) was necessary to fulfill the angel’s requirement. While speculative, this interpretation makes sense within the magical worldview where the physical presence of “the right person” might involve extraordinary measures.

The 1827 retrieval of the golden plates by Joseph Smith on September 22 blends folk magic rituals with dramatic flair, evoking a midnight heist straight out of a 19th-century adventure novel—complete with black garb, a borrowed carriage, and an astrologically auspicious hour that would make any treasure hunter chuckle. These details, drawn from family accounts and local records, highlight the theatricality of the event amid Smith’s treasure-seeking background, raising eyebrows about its supernatural claims.

Preparation Rituals: Smith purchased black fabric and “lamp black” paint from a Palmyra store on September 18, 1827, four days before the retrieval, suggesting deliberate staging for a cloaked appearance. He borrowed Joseph Knight Sr.’s black horse and carriage, donning the dark ensemble as required by the angel Moroni for the final ascent to the Hill Cumorah. Lucy Mack Smith’s 1845 memoir recounts the angel’s strict demand for “total blackness” in clothing and surroundings, with no light permitted—a nod to treasure-digging superstitions where darkness thwarted guardian spirits.

Theatrical Timing: The mission unfolded at 2:00–3:00 AM, aligning precisely with the “powerful hour” of Jupiter—Smith’s purported ruling planet per local astrologers like Samuel Tyler Lawrence—when celestial influences peaked for seers. This cosmic timing, borrowed from folk magic grimoires, added a layer of pseudoscientific gravitas; skeptics note it mirrors the witching hour of rural occult practices rather than divine spontaneity.

Eyewitness Accounts: Multiple witnesses corroborated the requirement for black clothing during this retrieval, and Lucy Mack Smith mentioned these darkness requirements in her Biographical Sketches.

According to historian D. Michael Quinn, Emma Smith accompanied Joseph to the hill, where “she stood with her back toward him, while he dug up the box,” and Martin Harris reported that “she kneeled down and prayed” during the retrieval. Joseph then “took the plates and hid them in an old black oak tree top which was hollow”.

The timing aligned with folk magic traditions: Joseph retrieved the plates at 2 am on the autumnal equinox—September 22, 1827—which treasure-digging practitioners considered “the most powerful time in magic”. This mirrored his first visit to the hill on September 22, 1823, also on the autumnal equinox. No independent witnesses observed the plates that night.

Cultural Context

These elements reflect 1820s New York’s treasure culture, where seer stones and midnight digs were commonplace but legally dicey post-1826 trial. Apologists frame the theatrics as angelic necessities against interference; detractors see opportunistic pageantry evolving Smith’s folkloric persona into prophecy. The absurdity—a prophet in blackface paint racing Jupiter’s hour—epitomizes Mormon origins’ blend of piety and pantomime.

Emma’s Strange Role: Although Smith claimed he needed the “right person” (identified through his seer stone as Emma Hale, whom he had recently married), Emma was instructed to stay near the carriage with her back turned away from the digging. This raises an obvious question: if the “right person’s” presence was essential, why was that person not allowed to witness or participate in the actual retrieval?

The Hollow Log Incident: Smith did not bring the plates home with Emma but claimed to hide them in a hollow log near Hill Cumorah. This decision makes little sense if he possessed an actual ancient artifact of immense religious significance. A lockbox could have been obtained en route, or the plates could have been hidden safely at home. Some historians theorize that Smith had not yet finished creating his “prop” plates but needed to claim retrieval on the magically significant autumnal equinox.

The Three Attackers: Perhaps the most fantastical element involves Smith’s claim that while carrying the 40-60 pound plates wrapped in a linen frock, he was attacked three times by treasure seekers. According to the January 2001 Ensign:

“As he was jumping over a log, a man sprang up from behind and gave him a heavy blow with a gun. Joseph turned around and knocked him to the ground, and then ran at the top of his speed. About half a mile further, he was attacked again in precisely the same way.”

This narrative expects readers to believe that Smith—who had a slight limp from childhood leg surgery—outran three gun-wielding attackers over three miles of terrain, fighting them off while carrying a 40-60 pound object and jumping over logs. The only injury he sustained was a dislocated thumb, which Dan Vogel speculates may have actually occurred while Smith was fashioning the binding rings for his prop plates.

The Spectacles: A Treasure-Digging Addition

The “Urim and Thummim” or spectacles represent another problematic element with treasure-digging origins. According to testimony from Willard Chase, fellow treasure-digger Samuel Lawrence accompanied Smith to Hill Cumorah around 1825-1826 to view the plates through his seer stone. Chase recounts:

“[Lawrence asked] if he had ever discovered anything with the plates of gold; he said no; he then asked him to look in his stone, to see if there was anything with them. He looked, and said there was nothing; he told him to look again, and see if there was not a large pair of specks with the plates; he looked and soon saw a pair of spectacles, the same with which Joseph says he translated the Book of Mormon.”

Historical Context

Chase, a neighbor and former digger with the Smiths, details ongoing treasure efforts; he lent Smith a seer stone found in 1822 while digging his well. Lawrence, a known astrologer and seer, joined as a potential “right person” for retrieval per guardian instructions. This predates Smith’s 1827 plates claim, suggesting the spectacles narrative emerged from peer pressure in treasure circles.

Corroboration and Debate

Joseph Knight Sr. confirms that Lawrence visited the hill with Smith. Apologists question Chase’s bias (anti-Mormon affidavit for Eber Howe); FAIR notes Chase’s own digging involvement. Critics see it exposing “Urim and Thummim” as improvised from seer stone lore, not divine. Smith’s histories retrofit biblical terms post-event.

This account, corroborated by Joseph Knight Sr., suggests the spectacles were not originally part of Smith’s vision but were added after Lawrence—another treasure-seer—challenged Smith’s credibility. In the competitive world of treasure digging, seers needed to demonstrate superior abilities. Smith appears to have been cornered into acknowledging the spectacles’ existence.

Significantly, Smith never actually used these spectacles during translation. Instead, he used the same chocolate-colored seer stone he had employed for treasure digging, placing it in a hat and pressing his face into the hat to block out light—the identical method he used when seeking buried treasure.

The Witnesses: Visions or Physical Observation?

The testimony of the eleven witnesses to the golden plates has been central to LDS apologetics since 1830. However, closer examination reveals significant problems with these testimonies that are rarely acknowledged in official church materials.

The Three Witnesses

Martin Harris, Oliver Cowdery, and David Whitmer comprised the Three Witnesses who testified to seeing an angel present the plates in June 1829. Their published testimony states:

“Be it known unto all nations, kindreds, tongues, and people, unto whom this work shall come: That we, through the grace of God the Father, and our Lord Jesus Christ, have seen the plates which contain this record… And we also know that they have been translated by the gift and power of God, for his voice hath declared it unto us; wherefore we know of a surety that the work is true.”

However, multiple contemporary accounts indicate these witnesses understood their experience as visionary rather than physical. John H. Gilbert, the typesetter for the first Book of Mormon, recalled asking Martin Harris directly: “Martin, did you see those plates with your naked eyes?” Harris replied: “No, I saw them with a spiritual eye.”

In 1838, Stephen Burnett reported that Martin Harris publicly stated in Kirtland, Ohio: “he never saw the plates with his natural eyes, only in vision or imagination.” This admission allegedly caused five influential members, including three apostles, to leave the church.

Similarly, David Whitmer in later interviews described the experience in visionary terms. When asked if he had seen the plates, he clarified that they were shown to him by an angel in a vision, not as a physical object he handled with his hands.

The Eight Witnesses

The Eight Witnesses (which included Smith’s father and two brothers, plus five members of the Whitmer family) testified to seeing and handling the plates. However, their statement is more ambiguous:

“Joseph Smith, Jun., the translator of this work, has shown unto us the plates… and as many of the leaves as the said Smith has translated we did handle with our hands; and we also saw the engravings thereon.”

Critically, all accounts indicate the Eight Witnesses only handled the plates while they were wrapped in cloth or placed in a covered box. Emma Smith, Joseph’s wife, described feeling the plates through a linen cloth and noted they seemed “pliable like thick paper, and would rustle with a metallic sound.” This description hardly requires gold plates—any metal sheets, or even cleverly arranged materials, could produce similar sensations through fabric.

Furthermore, the testimony states they handled “as many of the leaves as Smith has translated,” implying they did not examine the sealed portion or verify the total plate count. The entire experience appears stage-managed to prevent actual visual or tactile inspection of the plates themselves.

Witness Credibility Issues

All Three Witnesses eventually left the LDS Church after serious disputes with Joseph Smith. In 1838, Smith himself called them “too mean to mention; and we had liked to have forgotten them.” Oliver Cowdery was excommunicated in 1838 after accusing Smith of a “dirty, nasty, filthy affair” with Fanny Alger (an early plural marriage). Martin Harris was excommunicated after the failure of the Kirtland Safety Society bank, which he accused of fraud. David Whitmer broke with Smith over doctrinal issues and joined other splinter movements.

While all three later reaffirmed their witness of the Book of Mormon, their testimonies must be understood in the context of their visionary nature and the cultural milieu of 19th-century folk magic and religious enthusiasm.

Analysis of the Official Narrative and Instances of Hyperbole

The Translation Process: Seer Stones, Not Spectacles

The official LDS narrative has traditionally emphasized Joseph Smith translating by studying the golden plates with the Urim and Thummim (the spectacles). However, historical evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that Smith rarely, if ever, used these instruments. Instead, he employed the same brown seer stone he had used for treasure digging.

Multiple eyewitnesses—including Emma Smith, Martin Harris, David Whitmer, and others—described Smith placing the seer stone in a hat, burying his face in the hat to exclude light, and reading English words that appeared on the stone. Significantly, the plates themselves were often not even in the room during translation. As David Whitmer stated:

“I, as well as all of my father’s family, Smith’s wife, Oliver Cowdery and Martin Harris, were present during the translation… He did not use the plates in translation.”

This method of translation raises profound questions:

- Why were the plates necessary at all? If Smith translated by reading words that appeared on a seer stone without looking at the plates, what purpose did the plates serve? Were they merely stage props to lend credibility to the enterprise?

- Why did God preserve ancient records for millennia if they would not be used in translation? The narrative claims God preserved these sacred records through centuries of warfare and destruction, only to have them translated through a method that didn’t require their physical presence.

- How does this method differ from treasure digging? The translation method is identical to how Smith claimed to locate buried treasure—placing a stone in a hat and “seeing” information. If we reject the efficacy of this method for finding treasure (as Smith’s failed treasure-digging career demonstrates), why should we accept its reliability for translation?

The “Reformed Egyptian” Problem

The Book of Mormon claims the plates were written in “Reformed Egyptian,” a script allegedly developed by ancient American prophets. According to Mormon 9:32-33:

“And now, behold, we have written this record according to our knowledge, in the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, being handed down and altered by us, according to our manner of speech.”

Multiple problems plague this claim:

No Linguistic Evidence: No Egyptologist, linguist, or ancient Near Eastern scholar recognizes “Reformed Egyptian” as a historical language or script. Standard linguistic reference works contain no entry for such a language. If such a script existed and was used extensively enough to record the complex history found in the Book of Mormon, some archaeological or linguistic evidence should exist.

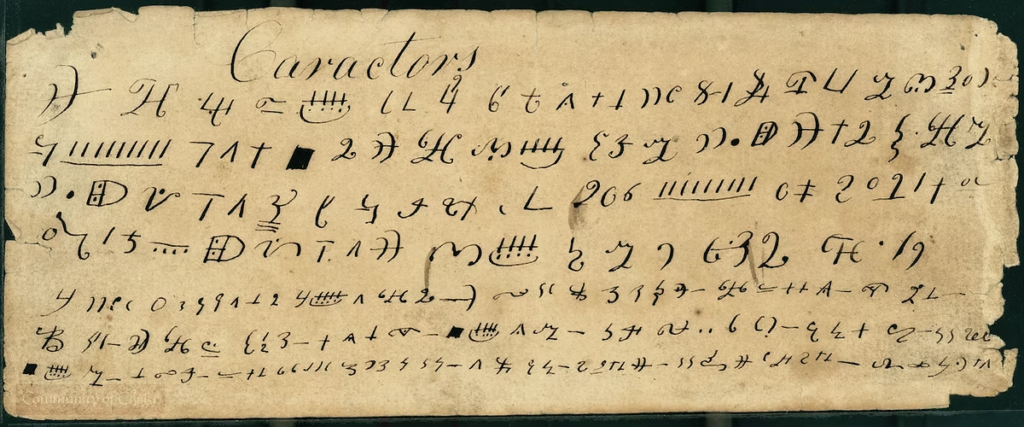

The Anthon Transcript: In 1828, Martin Harris took a sample of characters allegedly copied from the plates to Charles Anthon, a classics professor at Columbia College. According to Harris’s later account, Anthon initially provided a certificate of authenticity but tore it up upon learning of the plates’ supernatural origin. However, Anthon himself wrote a very different account, stating he immediately recognized the characters as a “hoax” composed of “Greek and Hebrew letters, crosses and flourishes, Roman letters inverted or placed sideways.” Here is a copy of the set of characters that Joseph Smith copied directly from the gold plates. The church has used these throughout the years and you can even see this image on their official website.

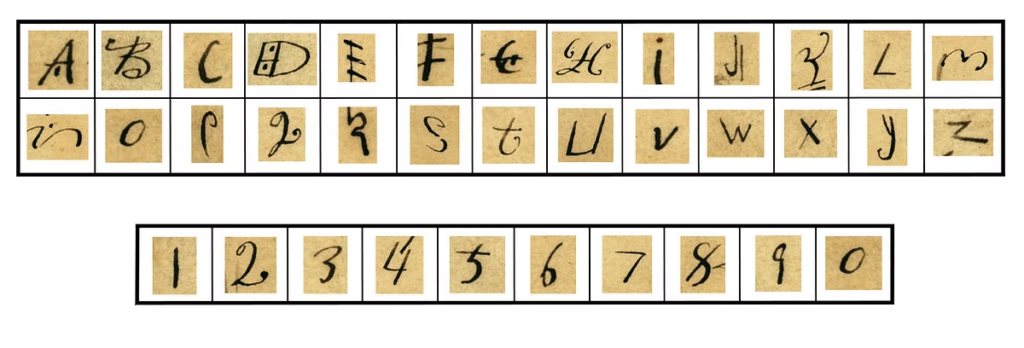

The problem, however, is that these characters in no way resemble Egyptian, but they do resemble someone who is trying to crudely modify the language they do know. Below is an image that takes all of the Book of Mormon characters and by simply rotation, creates the alphabet we are all used to.

During Joseph Smith’s early ministry, there was no one in his immediate environment in rural upstate New York who could genuinely read Egyptian, and the academic decipherment of the language was still in its infancy. Jean-François Champollion announced his breakthrough on the Rosetta Stone only in the 1820s, and while scholarly circles in Europe and some American institutions began to take notice, this could have been on the radar of Palmyra farmers and village printers in the late 1820s. But when Smith acquired Egyptian papyri in Kirtland in 1835 and began his “Egyptian project,” his own papers show that he and his clerks were working from assumptions and homegrown “rules” rather than any formal training in Egyptology.

The specific term “Reformed Egyptian” appears only in the Book of Mormon itself (Mormon 9:32–34) and in subsequent Latter-day Saint discussion; standard reference works in linguistics and Egyptology do not list it as a recognized language or script. A survey of professional opinion summarized in modern overviews notes that no non‑LDS Egyptologist or ancient‑language specialist accepts “Reformed Egyptian” as an identifiable historical language or script, nor has any external inscription been found that matches the Book of Mormon “caractors.” Assessments of the so‑called Anthon Transcript—the sheet of characters Martin Harris took to classicist Charles Anthon—conclude that the characters cannot be linked in any robust way to known Egyptian scripts beyond a few superficial resemblances that could just as easily arise from doodling, imitation, or random symbol creation.

Linguistic Implausibility: Egyptian writing systems (hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic) are fundamentally phonetic. They require substantial text to convey meaning—there is no “condensed” form where single characters represent paragraphs of English text. The 12 plates that supposedly comprised the “unsealed” portion would need approximately 22,000 English words per plate (based on the 590-page first edition Book of Mormon). This would require impossible character density and complexity, far exceeding anything found in actual ancient Egyptian texts.

Mathematical Impossibilities: Comparative examples from Smith’s time demonstrate the implausibility. The Pyrgi Tablets, often cited by LDS apologists as evidence of ancient metal records, contain only about 200 words across three plates densely packed with characters. For the golden plates to contain the Book of Mormon, each plate would need to hold 330 times more information than the Pyrgi Tablets—an absurdity.

Rosetta Stone Connection: The Maumee Express (November 18, 1837)

The Maumee Express, a newspaper in Maumee, Ohio (near Kirtland, where Joseph Smith then resided), published a short notice on page 2 under “Antique”: The Curators of the Albany Institute [Albany, New York] acknowledge the donation of a copy in plaster of the Rosetta Stone, now in the British Museum, from Henry James Esq.”

Northwest Ohio newspapers like the Maumee Express circulated LDS-related news; e.g., February 1, 1838, reported Smith’s arrest on banking charges. Egyptomania items, such as the November 18, 1837, Rosetta Stone notice, reflect awareness in Smith’s sphere during his Egyptian papyri work (1835–1842). Smith sent letters to editors and tracked press coverage, making such publications part of his information milieu.

Hyperbolic Elements in the Narrative

Several aspects of the golden plates story contain hyperbolic or miraculous elements that strain credibility:

Weight Inconsistencies: Witnesses estimated the plates’ weight at 40-60 pounds—manageable enough for Joseph Smith to allegedly sprint through the woods while fighting off multiple attackers, leap over logs, and outrun armed treasure hunters in a theatrical performance worthy of an action hero. However, if the plates were actually solid gold with the dimensions described (six inches wide by eight inches long, with leaves “not quite so thick as common tin”), they would weigh approximately 140 pounds—roughly the equivalent of hauling a full-grown Great Dane through the forest while engaged in hand-to-hand combat.

To rescue the narrative from this mathematical embarrassment, LDS apologists have desperately speculated about a gold-copper alloy (tumbaga) to account for the impossibly lighter weight. But this creative metallurgical gymnastics creates a far more awkward problem: why enthusiastically call them “golden plates” throughout scripture, church history, and millions of missionary discussions if they weren’t primarily gold? The entire mystique collapses into “the gold-ish plates” or “the kinda-sorta-metallic-but-not-really-golden plates.”

Moreover, Josiah Stowell’s testimony that a corner of the plates exhibited a “greenish cast” suggests copper oxidation —a chemical reality that further demolishes the “gold” designation, since gold doesn’t oxidize or tarnish. The plates were apparently gold in name only, their gleaming divine provenance reduced to common copper with a marketing problem. One might charitably suggest they were simply “gold-colored,” which would make them the ancient American equivalent of fool’s gold—an assessment critics find deliciously appropriate for the entire enterprise.

Official-adjacent (FAIR, BYU Studies): Plates likely tumbaga (gold-copper alloy, Mesoamerican); ~53 pounds for dimensions, hard enough for engraving, acid-gilded for golden shine. Explains “golden” appearance despite lightness.

Tumbaga, the gold-copper alloy often proposed for the Book of Mormon’s “golden” plates, first emerges archaeologically around 500–300 BCE in the Tumaco-La Tolita culture along Ecuador and Colombia’s coast, with precursors as early as 780 BCE, before becoming widespread from 200 BCE to 800 CE across South and Central America. In Mesoamerica—popular in LDS models—it appears in Panama and Costa Rica by 300–500 CE, among the Moche in Peru (100–800 CE), and in Maya lowlands around the 5th century CE, aligning partially with the Book of Mormon’s Nephite timeline (600 BCE–421 CE) at its onset but peaking later. This coastal, post-Lehi distribution raises questions for Heartland theories lacking such metallurgy.

The Cave Full of Records: Several early Mormon leaders claimed that Joseph Smith and others returned the plates to a cave within Hill Cumorah containing “many wagon loads” of other ancient records, the Sword of Laban, and other artifacts. Given that Joseph Smith’s entire narrative already required accepting angelic visitations, invisible golden plates, translation via seer stone in a hat, and guardian spirits protecting buried treasure, the addition of a secret cave crammed with ancient weaponry and archival materials represents mythology and hyperbole operating at full throttle—not an aberration, but the natural escalation of increasingly fantastic claims.

This “treasure cave” story has never been substantiated and reads precisely like the treasure-digging folklore from which it emerged. In the 19th-century treasure-hunting culture that shaped Smith’s early career, buried treasures were routinely guarded by spirits, moved deeper into the earth, and accompanied by vast hoards of additional riches just beyond reach. The Hill Cumorah cave simply transplants this folk magic template into a religious context: the treasure hunter’s dream of endless wealth becomes the prophet’s vision of endless records, the enchanted guardian becomes the angel Moroni, and the elusive gold becomes conveniently returned artifacts that—surprise—no one can verify.

When your foundational claim already stretches credulity to include gold plates no one could see, translated by putting your face in a hat, the addition of a Nephite warehouse full of swords and scrolls barely registers as additional mythology. It’s simply par for the course in a narrative where hyperbole and the miraculous had already become standard operating procedure.

Church History Library blog (2020): Acknowledges cave stories from Cowdery via Young/Kimball; notes Hill Cumorah’s drumlin geology unlikely for natural caves, possibly visionary/dream. BYU Journal of Book of Mormon Studies (2004): Compiles 10 secondhand accounts (1855–1882, e.g., W.W. Phelps via Hyrum Smith, David Whitmer interviews); interprets as teaching future records, God’s treasures.

No firsthand Joseph Smith record; all post-1850, second-/third-hand. Resembles 19th-century treasure legends (e.g., Miner’s Hill cave confusion). No archaeological evidence; modern Church emphasizes visionary nature, not literal repository.

The Sealed Portion: The Book of Mormon’s golden plates consisted of two distinct sections: a smaller unsealed portion yielding the ~500-page text translated by Joseph Smith, and a larger sealed portion comprising roughly two-thirds of the total volume, bound with cords or cement that prohibited access. Smith’s 1838 account (Joseph Smith—History 1:62) describes the sealed part as containing “a revelation from God, from the beginning of the world to the ending thereof,” echoing Ether 4:6’s promise of cosmic mysteries, lost tribes’ records, and Christ’s ministry details withheld until humanity achieves faith akin to 3 Nephi’s multitudes.

2 Nephi 27:7–10 (mirroring Isaiah 29’s sealed book) warns that premature unsealing would cause the plates’ destruction and Smith’s death; divine command sealed them post-Nephite fall until the Lord’s timing (Ether 4:5–7; D&C 17:26). Witnesses like John Whitmer handled the sealed heft but saw no contents; the Eight Witnesses viewed only unsealed leaves. Post-translation, Smith returned the full set to Moroni, rendering verification impossible.

Narrative and Apologetic Functions

-

Translation Excuse: Explains halting after the lost 116 pages (D&C 3, 10)—God forbade replacement from sealed records.

-

Eschatological Incentive: Promises “greater things” (Ether 4:11) motivate obedience, mirroring biblical withheld revelations (Daniel 12:4, Revelation 5).

-

Empirical Shield: Unseen contents evade challenges like script illegibility or archaeological absence.

LDS scholars frequently cite Revelation 5:1–10—where a sealed scroll is opened only by the Lamb—as a prophetic archetype for Moroni’s plates, with 2 Nephi 27 fulfilling Isaiah 29’s “sealed book” motif. The Dead Sea Scrolls offer compelling ancient precedent, such as the Genesis Apocryphon sealed in jars (Qumran Cave 1) and the Copper Scroll (Cave 3) enumerating hidden treasures much like withheld records. FAIR further notes that the physical sealing method (cement or cords) parallels the Nag Hammadi codices, effectively safeguarding sacred content until the appointed divine timing.

Critics contend that the sealed portion served as a convenient narrative device amid 1829 pressures for more text following the loss of the 116 pages (D&C 10), where no further production occurred despite prophetic promises—much like unfulfilled eschatological hooks that sustained movements such as the Millerites. As LDS Discussions highlights, its unverifiability echoes the Kinderhook Plates hoax, with Martin Harris’s demands for expansion suggesting ad hoc invention to halt translation amid fatigue and urgency. The absence of any surfacing artifact only bolsters claims that it functioned more for narrative utility than historical substance.

Scriptural Description

In 2 Nephi 27:7–10—directly echoing Isaiah 29:11’s vision of a sealed book that no one can read—a divine voice warns Joseph Smith that any premature attempt to unseal the plates would trigger their destruction and his own death, while the sealed portion preserves mysteries “which shall be revealed hereafter to the children of men in his own due time.” Ether 4:5–7 reinforces this: Moroni personally sealed profound revelations (including Christ’s full ministry and lost tribes’ records) until humanity achieves the same faith demonstrated during Christ’s American ministry in 3 Nephi, promising that “greater things” await the worthy.

Smith’s Descriptions and Scope

Smith’s 1832 history describes the sealed section as containing “a revelation from God, from the beginning of the world to the ending thereof,” vastly exceeding the unsealed portion’s ~500 printed pages (covering ~1,000 years Nephite/Jaredite history). His 1838 canonized account (Joseph Smith—History 1:62) adds that the plates’ top portion was cemented shut to the edge, inaccessible even to the Eight Witnesses who hefted but never inspected it.

Credibility Under Scrutiny

This “sealed revelation” motif raises piercing questions: Why invent a divine death threat (2 Nephi 27) if the plates were genuine artifacts—did Smith fear mortal inspection more than angelic wrath? The conditional future promise (Ether 4) mirrors countless unfulfilled prophecies across religions, conveniently deferring falsification indefinitely; nearly 200 years later, no unsealing has occurred despite millions of professed believers, suggesting a perpetual carrot for retention rather than testable prophecy. If the sealed content truly spanned cosmic history, why withhold it behind such a flimsy faith-threshold, and how could thin metal leaves plausibly encode eternity’s narrative without exponentially thicker plates? The total absence—returned to Moroni, never reexamined—renders the claim psychologically compelling yet empirically empty, smelling more of 1829 narrative improvisation than ancient precaution.

Retrieval and Handling Accounts

Smith’s 1838 Joseph Smith—History (Pearl of Great Price 1:52–62) describes the plates in a stone box: the top ~2 inches sealed to the plates’ edge, with the rest engraved and translatable. Witnesses like the Eight (who handled the unsealed portion) confirmed a sealed edge but never saw contents. Emma Smith and others noted the sealed heft made carrying tricky, yet no one inspected inside. Returned to Moroni post-translation, the plates vanished, precluding verification.

Narrative Functions

- Translation Limit: Explains brevity—Smith stopped after ~116 pages were lost (D&C 3, 10), claiming divine prohibition on more.

- Future Promise: Ether 4 dangles “greater things” for the faithful, sustaining 19th-century converts amid skepticism.

- Verification Shield: Unseen content dodges challenges like Anthon’s dismissal of “reformed Egyptian” samples or absent artifacts. Critics liken it to apophatic theology—truth in what’s withheld.

Comparative Illustrations from the Development of the Biblical Canon

The Crucially Different Canonization Processes

The formation of the biblical canon occurred through radically different processes than the production of the Book of Mormon, highlighting fundamental theological and historical distinctions.

The biblical canon emerged gradually over ~400 years through rigorous, decentralized processes involving apostolic authorship, doctrinal consistency, widespread church usage, and formal ratification by councils like Rome (382 AD), Hippo (393 AD), Carthage (397 AD), and Trent (1546 AD), ensuring collective discernment under the Holy Spirit. In stark contrast, the Book of Mormon materialized instantaneously in 1829 via Joseph Smith’s singular dictation—~3 months for 500+ pages—declared complete without debate, printed in 5,000 copies (only ~500 survive), and canonized unilaterally by Smith despite later edits (1837 stereotyping, 1840 revisions). This solitary origin, lacking communal vetting or centuries of liturgical testing, underscores fundamental theological chasms: a divinely inspired corpus refined by the church versus a prophet’s unfiltered revelation demanding immediate acceptance.

Multiple Authors Across Centuries: The biblical canon developed through contributions from dozens of authors across approximately 1,500 years (Old Testament) and about 50 years (New Testament). This multi-generational, multi-author approach provided internal checks and balances, with later texts referencing and validating earlier ones, creating a complex web of textual witnesses.

In contrast, the Book of Mormon claims to be an abridgment by two individuals (Mormon and Moroni) of earlier records, all translated by one person (Joseph Smith) over a period of about 65 working days. This singular authorship creates a vulnerability to individual error, bias, or deception absent from the biblical model.

Manuscript Evidence and Textual Criticism: The New Testament boasts unparalleled attestation: ~5,800 Greek manuscripts, 10,000 Latin, and 9,300 in other languages, spanning from the 2nd century onward, enabling textual critics to reconstruct the original with over 99% confidence despite minor variants (e.g., spelling, word order).[ from prior] Disputed passages like the long ending of Mark (16:9–20) or the woman taken in adultery (John 7:53–8:11) are transparently footnoted in modern Bibles, reflecting rigorous scholarship rather than concealment. These facts alone demolish the LDS “Great Apostasy” narrative and claims of “precious truths” lost through corruption— if core doctrines were systematically excised, how could thousands of manuscripts, widely disseminated across continents, preserve such unanimity on Christology, salvation, and ecclesiology? The abundance refutes any notion of wholesale textual unreliability, positioning the Bible as a stable foundation against Restorationist revisions.

The Book of Mormon has no ancient manuscript tradition whatsoever. The entire text rests upon Joseph Smith’s claimed translation, with the original “golden plates” conveniently returned to an angel and unavailable for examination. The original manuscript (handwritten by scribes as Smith dictated) and printer’s manuscript exist, but these only preserve Smith’s English dictation, not the claimed ancient source.

Canonical Recognition Through Church Councils: The biblical canon was recognized (not created) through careful deliberation by church councils (e.g., Hippo in 393 CE, Carthage in 397 CE) that applied specific criteria: apostolic authorship or association, orthodox theology, widespread church usage, and spiritual edification. These councils debated which books merited inclusion, acknowledging some texts (like James, 2 Peter, 2-3 John, Jude, Revelation) required more scrutiny due to questions about authorship or theology.

The Book of Mormon bypassed any such process. Joseph Smith declared it scripture based solely on his claimed angelic encounter and translation experience. No council deliberated, no external validation occurred, and no scholarly examination of source documents was possible.

Historical Verification vs. Unverifiable Claims

Archaeological Corroboration: Biblical archaeology has confirmed numerous people, places, and events mentioned in Scripture. While not every biblical claim has archaeological support (nor should we expect it, given the selective nature of archaeological preservation), substantial evidence exists for:

- The existence of biblical cities (Jerusalem, Jericho, Babylon, Nineveh, etc.)

- Historical figures (King David, Pontius Pilate, Herod the Great, etc.)

- Major events (the Babylonian exile, Roman occupation of Judea, etc.)

- Cultural practices described in biblical texts

Despite over 150 years of exhaustive searching by LDS scholars and enthusiasts, no conclusive archaeological evidence substantiates the Book of Mormon’s historical claims—leaving its narrative adrift in a vacuum of unverifiable assertions. No ancient American civilization employed “Reformed Egyptian,” a script absent from Mesoamerican inscriptions or any known corpus; feeble apologetic efforts to link Anthon Transcript doodles to modified Hebrew/Egyptian hieratic symbols crumble under Egyptological scrutiny, as even FAIR concedes no direct matches exist.

No excavated sites align with Zarahemla, Bountiful, or other named cities—LDS attempts like Sorenson’s narrow Mesoamerican model (e.g., Kaminaljuyu as “Zarahemla”) falter against mismatched timelines, population scales, and absent Book of Mormon-specific artifacts like Liahona brass balls or steel swords. The text’s portrayal of advanced civilizations with horses, chariots, steel, wheat, and millions in battle casualties finds zero corroboration in the pre-Columbian record, where metallurgy lagged, horses vanished post-Ice Age until Spanish reintroduction, and no Hebrew-derived cultures appear.

DNA evidence decisively refutes Lehi’s Israelite colony as Native American progenitors; modern genomic studies (e.g., 99%+ East Asian/Siberian haplogroups) preclude Middle Eastern input, despite apologetic pivots to “limited geography” or “genetic wipeout” via post-Lehi migrations—speculative dodges that strain credulity without positive evidence. These gaps expose the Book of Mormon less as history than 19th-century invention.

Geographic and Linguistic Reality: The Bible describes real places that can be visited today—Jerusalem, Nazareth, the Jordan River, Rome, etc. The languages in which it was written (Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek) are well-attested ancient languages with extensive literary traditions beyond the Bible.

The Book of Mormon describes places that cannot be located and was allegedly written in a language (“Reformed Egyptian”) that no scholar recognizes. The text itself contains anachronisms (steel, horses, wheat, etc., in pre-Columbian America) and borrows extensively from the 1769 King James Bible, including its translation errors—suggesting 19th-century composition rather than ancient American origin.

Miraculous Claims: Biblical Prophecy vs. Treasure-Digging Folk Magic

Biblical Miracles in Historical Context: Biblical miracles occur within verifiable historical frameworks. The Exodus, while debated regarding exact date and scale, fits within the broader context of Egyptian history and Near Eastern migrations. Jesus’ ministry is situated in first-century Judea under Roman rule—a thoroughly documented historical period. The resurrection claim is supported by multiple independent witness accounts and the willingness of early Christians to die for their testimony.

The golden plates narrative incorporates elements of 19th-century American folk magic and treasure-digging practices:

- Guardian spirits (common in treasure-digging lore)

- Treasures that “slip” deeper into the earth (treasure-digging belief)

- Required magical timing (autumnal equinox)

- Seer stones (used by treasure diggers)

- The “power of three” (three attempts, three witnesses)

- Specific clothing colors (black)

These elements are absent from biblical accounts of divine revelation. Moses didn’t need a magical stone to translate the tablets; the Ark of the Covenant wasn’t hidden by a guardian spirit that required magical rituals for retrieval; the apostles didn’t testify to seeing Jesus in “spiritual vision” but insisted on his physical resurrection.

The Unique Problem of Single-Source Scripture

Comparison to Other Faith Traditions

The golden plates narrative presents a unique problem: vast divine revelation mediated exclusively through one individual with no verifiable source documents, no contemporary corroboration, and no independent verification. Ironically, both traditional Christianity and Mormonism reject similar claims from other movements—Islam’s angelic delivery of the Quran, or newer prophets citing private revelations—yet Mormonism demands acceptance of essentially the same pattern for Joseph Smith’s golden plates.

Islam: Muhammad’s revelations were memorized and recorded by multiple companions during his lifetime, with Arabic manuscripts dating within decades of his death. Multiple transmission chains (isnad) allow textual criticism—not dependent on a single miraculous object shown only to relatives.

Buddhism: The Buddha’s teachings were preserved by monastic communities across cultures and languages. The Pali Canon, Chinese, and Tibetan texts provide overlapping accounts, allowing reconstruction of core teachings—without golden plates shown to select witnesses.

Hinduism: The Vedas developed over centuries through priestly oral traditions and multiple schools, allowing textual comparison and widespread manuscript attestation.

Christianity: The New Testament comprises 27 books by multiple authors with thousands of manuscript copies enabling textual verification. The canonical process involved centuries of church deliberation and multiple witnesses to Jesus and early church events.

The golden plates stand alone: one translator, zero manuscripts, eleven witnesses (most family members), and conveniently retrieved source documents.

The Golden Plates as Unique and Problematic

The Book of Mormon stands virtually alone in religious history as:

- A large volume of scripture (584 pages in the first edition) was produced by one person in approximately 65 working days

- Translated from a source document never available for examination by any qualified scholar

- Written in a language unknown to linguistics or Egyptology

- Describing a civilization for which no archaeological evidence exists

- Witnessed by individuals who described visionary rather than physical experiences

- Incorporating elements of contemporary folk magic and treasure-digging practices

- Produced by someone with no linguistic training or knowledge of ancient Near Eastern languages

This combination of factors creates a credibility gap that LDS apologetics struggle to bridge. The closest parallels are not other major world scriptures but rather texts produced by other 19th-century American religious movements (e.g., James Strang’s Voree Plates) or modern religious movements making similar unverifiable claims.

James Strang, a charismatic Mormon schismatic who claimed succession to Joseph Smith after his 1844 assassination, announced in 1845 the discovery of the Voree Plates—three small brass plates unearthed in Voree, Wisconsin, beneath an oak tree on the “Hill of Promise.” Guided by an angelic vision akin to Moroni’s, Strang led four witnesses (Aaron Smith, Jirah B. Wheelan, James M. Van Nostrand, and Edward Whitcomb) to the spot, where they dug without prior disturbance and retrieved the encased plates, complete with a pictorial priesthood diagram and alphabetic script. Unlike Smith’s hidden golden plates, Strang publicly displayed his for examination by Mormons and skeptics alike, translating them as The Record of Rajah Manchou of Vorito—a lost chronicle validating his prophetic mantle. The plates bolstered his Strangite faction (~300 followers at peak) but were later lost; modern analysis deems them 19th-century forgeries, mirroring—and arguably surpassing—Smith’s own unverifiable metal record claims.

The Voree Plates bolstered Strang’s assertion that Voree, Wisconsin—not Utah’s Salt Lake Valley—served as the divinely ordained new gathering site for Latter Day Saints. His published translation, styled as The Record of Rajah Manchou of Vorito, holds scriptural status among Strangite adherents and select successor groups, though no mainstream Latter Day Saint denominations recognize it.

Unlike Joseph Smith’s elusive golden plates, which fueled the Book of Mormon yet vanished without non-believer scrutiny, Strang’s artifacts underwent public inspection by independent parties, including typewriter pioneer Christopher Latham Sholes. Detractors charged Strang with forging them from a brass teapot—a rumor he and his supporters hotly refuted. The plates mysteriously vanished around 1900, their fate unresolved to this day.

The Sealed Portion and Perpetual Promise

The concept of the “sealed portion” deserves special attention as it reveals the self-perpetuating nature of the golden plates narrative.

According to 2 Nephi 27:7-8:

“And it shall come to pass that the Lord God shall bring forth unto you the words of a book, and they shall be the words of them which have slept. And behold the book shall be sealed; and in the book shall be a revelation from God, from the beginning of the world to the ending thereof.”

This sealed portion allegedly constituted approximately two-thirds of the plates. Joseph Smith claimed these portions were bound together so tightly they couldn’t be separated, appearing “as solid to [David Whitmer’s] view as wood.”

Theological and Practical Problems

Perpetual Incompleteness: The sealed portion ensures the Book of Mormon remains perpetually incomplete. Believers are promised that at some future time, when they prove sufficiently faithful, the sealed portion will be revealed. This creates a theological carrot that maintains engagement while never requiring fulfillment. Traditional Christianity, by contrast, affirms the sufficiency and completeness of biblical revelation (2 Timothy 3:16-17, Hebrews 1:1-2).

The “Fullness of the Gospel” Contradiction: LDS theology claims the Book of Mormon contains the “fullness of the gospel,” yet two-thirds of the plates remain sealed and unavailable. How can the Book of Mormon contain the gospel’s fullness if most of its content remains hidden? This creates an internal contradiction regarding the book’s completeness and authority.

The Convenience Factor: The sealed portion proves remarkably convenient for addressing potential criticisms:

- Can’t produce more plates? They’re sealed.

- Why so short compared to the Bible? The sealed portion is much longer.

- Why doesn’t the Book of Mormon answer this theological question? The sealed portion probably addresses it.

- Can critics examine the plates? No, they’ve been returned to an angel, and the sealed portion was never opened anyway.

This perpetually deferred revelation resembles the structure of a confidence scheme more than a genuine prophetic tradition.

Unanswered Questions That Foster Skepticism

The golden plates narrative generates a staggering volume of questions that remain conspicuously inadequately answered by official LDS sources or apologetic literature—though to be fair, producing “good” answers to this many glaring inconsistencies would require skills bordering on the miraculous:

Questions About Physical Logistics

Weight and Portability: If the plates were as described (six inches by eight inches, with enough leaves to produce 584 pages of English text), and made of gold or even a gold-copper alloy, could a young man with a leg disability actually carry them three miles through forest terrain while fighting off attackers? The physics seem improbable at best.

The Guardian Paradox: If a spiritual entity (Moroni) could remove the physical plates from Smith’s possession as punishment for disobedience (as claimed after the loss of the 116 pages), how did this non-physical being manipulate a physical object? This raises broader questions about angel-matter interactions that traditional Christian theology carefully navigates through incarnation and theophany concepts, but which the golden plates narrative treats casually.

An Irrelevant Angelic Warning: Moroni’s warnings to Joseph Smith explicitly prohibited using the golden plates for personal financial gain—insisting they served divine purposes alone—yet this directive loses much of its logical force when considering the plates’ inevitable return to angelic custody after brief translation use, rendering any potential profiteering impossible from the outset. If heaven mandated their retrieval regardless (as Smith repeatedly claimed), why issue such a superfluous prohibition, as if Smith might hawk the artifacts on Palmyra’s market square? The emphasis on non-commercial intent feels more like preemptive narrative armor—deflecting anticipated skepticism about a treasure-seeker’s motives—than a genuine divine safeguard, especially amid Smith’s folk-magic background, where unearthed hoards typically fueled get-rich-quick schemes. This tension underscores a contrived cautionary tale, pledging restraint for an object never destined to be kept

Why No Physical Etchings or Rubbings?: In 19th-century America, creating etchings or rubbings of inscribed surfaces was common practice. Why didn’t Smith create verifiable physical copies of the plate inscriptions? Such copies would have provided tangible evidence, allowed scholarly verification, and removed all doubt. The Anthon Transcript represents the only alleged copy, and Charles Anthon himself denounced it as fraudulent. There is no official record that Moroni prohibited Smith from making the etching.

The “Other Treasures?: The retrieval narrative’s vanishing plates and “other treasures” evoke a tantalizing mystery—what exactly lurked in that stone box alongside the gold? Smith’s accounts, echoed by followers like Joseph Knight and Lucy Mack Smith, paint a scene straight out of folklore: divine guardians thwarting the unprepared prophet, hurling him to the ground thrice before relenting. One can’t help but ponder if these unnamed treasures—perhaps seer stones, scrolls, or rival relics—hinted at a larger hoard, mirroring the treasure-digging lore Smith knew well, where enchanted caches demanded ritual purity. The reappearance inside the resealed box adds poetic irony: a prophet bested by his own prize, underscoring faith’s trial over possession. This vignette, blending miracle with mishap, invites reflection on whether it reveals heavenly drama or a storyteller’s flourish to explain initial fumbles.

1,500 Years of Protection – A Question of Divine Consistency: If Moroni meticulously guarded the golden plates for 1,500 years in a shallow Hill Cumorah burial—thwarting decay, animals, and looters—why couldn’t the angel extend that same supernatural protection against thieves once Joseph Smith retrieved them? This puzzle arises from Smith’s own 1838 account (Joseph Smith—History 1:52–59), where Moroni delivers a stern warning post-retrieval: “do not thrust your hand into the box until the proper time to obtain the plates arrives; for if you do, you will injure yourself.”[ from prior] Yet Smith faced repeated “electric shock” rebukes only during his premature retrieval attempts, not afterward against reported threats like the lost 116 pages. The contrast highlights a narrative tension: invincible heavenly safeguarding for centuries, but vulnerability post-handover, prompting thoughtful scrutiny of the miracle’s selective application.

FAIR: Attempts to steal the gold plates from Joseph Smith

Question: What did Joseph Smith say about efforts that were made to steal the gold plates from him?

At length the time arrived for obtaining the plates, the Urim and Thummim, and the breastplate. On the twenty-second day of September, one thousand eight hundred and twenty-seven, having gone as usual at the end of another year to the place where they were deposited, the same heavenly messenger delivered them up to me with this charge: that I should be responsible for them; that if I should let them go carelessly, or through any neglect of mine, I should be cut off; but that if I would use all my endeavors to preserve them, until he, the messenger, should call for them, they should be protected. (Joseph Smith History 1:59)

Questions About Translation Methodology

The Spectacles Paradox: Why did the angel provide special interpreting instruments (Urim and Thummim/spectacles) that Smith never actually used? All reliable accounts indicate he used his chocolate-colored treasure-digging seer stone instead. This suggests the spectacles were narrative props rather than functional instruments.

The Unnecessary Plates: If Smith translated by reading English words that appeared on his seer stone, without looking at the plates, and if the plates weren’t even present during much of the translation, what purpose did they serve? This question strikes at the heart of the entire enterprise.

Reformed Egyptian Efficiency?: The Book of Mormon claims reformed Egyptian was chosen because it was more compact than Hebrew (Mormon 9:33). However, Egyptian script is fundamentally phonetic and requires substantial text for expression. The idea that it could compact the Book of Mormon’s equivalent onto metal plates defies linguistic reality.

Questions About Divine Purpose and Methods

Why This Convoluted Method?: If God wished to restore truth in the 19th century, why use this elaborate method involving buried gold plates, seer stones, and treasure-digging tropes? Why not simply inspire Joseph Smith to write, as Christians believe God inspired biblical authors? The convoluted methodology raises more questions than it answers.

The Canon Problem: Traditional Christianity affirms that the canon was closed with the apostolic age (Revelation 22:18-19). If the Book of Mormon represents divine scripture, how do we reconcile this with biblical warnings against adding to God’s word and Paul’s denunciation of “another gospel” (Galatians 1:8)?

Moroni’s Foreknowledge Problem: Why did Moroni tell Smith in 1823 to bring his brother Alvin the next year when Alvin would die months before that date? Either Moroni lacked foreknowledge (problematic for an angel), or the command was intended for some purpose we don’t understand, or the story is fabricated.

Questions About Witnesses and Credibility

The Vision vs. Physical Observation Problem: Why do multiple accounts indicate the Three Witnesses experienced a vision rather than a physical observation? Martin Harris’s admission that he saw the plates with “spiritual eyes” rather than “natural eyes” fundamentally undermines the nature of his testimony. Spiritual visions prove subjective experience, not objective historical fact.

The Covered Plates Problem: Why were the Eight Witnesses only permitted to handle the plates through cloth? If the plates were genuine ancient artifacts, what risk would visual or tactile examination pose? The restriction suggests the plates couldn’t withstand close inspection.

The Disaffection Pattern: Why did all Three Witnesses eventually leave the LDS Church after serious conflicts with Joseph Smith? While they later reaffirmed their witness to the Book of Mormon, their willingness to break with Smith over other issues raises questions about the independence and reliability of their earlier testimonies.

Questions About Historical and Archaeological Evidence

Where Is the Archaeological Evidence?: After 150+ years of searching, why is there such limited archaeological evidence emerged supporting the Book of Mormon’s historical claims? The complete absence of evidence for Reformed Egyptian, the described civilizations, or the mentioned cities and locations is staggering compared to biblical archaeology’s abundant confirmations.

The DNA Evidence Problem: Genetic studies of Native American populations show no significant connection to ancient Near Eastern peoples. How does this square with the Book of Mormon’s claim that Lamanites (Native Americans) descended from Lehi’s family from Jerusalem around 600 BCE?

The Anachronism Problem: How do we explain horses, steel, wheat, and other Old World plants and animals mentioned in the Book of Mormon when these didn’t exist in pre-Columbian Americas? LDS apologists’ attempts to redefine these terms (horses = tapirs, steel = natural meteor iron) strain credibility.

Conclusion: Implications for Faith and Historical Understanding

The Traditional Christian Perspective

From a traditional Christian viewpoint, the golden plates narrative presents insurmountable theological and historical problems:

Sufficiency of Scripture: Historic Christianity affirms that the Bible contains all truth necessary for salvation and godly living (2 Timothy 3:16-17). The Westminster Confession states: “The whole counsel of God, concerning all things necessary for his own glory, man’s salvation, faith, and life, is either expressly set down in Scripture, or by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture: unto which nothing at any time is to be added.” The claim of additional scripture fundamentally challenges this doctrine.

Closed Canon: The early church recognized the canon’s closure with the apostolic age. Revelation 22:18-19 warns against adding to the prophetic word. While LDS theology argues this applies only to Revelation, the broader principle of a closed, sufficient canon permeates historic Christian belief.

Nature of Revelation: Biblical revelation occurred through prophets whose credentials were validated by fulfilled prophecy (Deuteronomy 18:21-22), miraculous signs confirming their message (Hebrews 2:3-4), and consistency with prior revelation. Joseph Smith’s career is marked by failed prophecies (temple in Independence, Missouri), supernatural claims grounded in folk magic rather than biblical precedent, and teachings contradicting orthodox Christianity (nature of God, pre-existence, plural marriage, etc.).

The Gospel Itself: The Book of Mormon’s theological content, while superficially Christian in places, ultimately presents a different gospel than biblical Christianity. It denies the Trinity, affirms works-based salvation (2 Nephi 25:23: “it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do“), and introduces doctrines (pre-existence, eternal progression, temple marriage for exaltation) absent from and contrary to biblical teaching.

The Historical-Critical Perspective

From a purely historical and critical standpoint, the evidence strongly suggests the golden plates narrative represents a 19th-century creation rather than ancient history:

Treasure-Digging Origins: The narrative’s deep roots in treasure-digging culture, folk magic, and occult practices of 1820s rural New York are undeniable. The methodology, terminology, timing, and even the progression of Smith’s story from treasure-seeking to religious founding follow predictable patterns of folk magic practitioners transitioning to religious authority.

Evolution of the Narrative: The story evolved significantly over time, with details added, modified, or corrected across different accounts. The angel’s identity shifted (unnamed angel → Nephi → Moroni), the purpose and use of the spectacles changed, and miraculous elements increased with retelling—patterns typical of legend development rather than historical reporting.

The Translation Process: Smith’s use of his treasure-digging seer stone, placed in a hat to exclude light, mirrors his earlier magical practices so completely that it’s difficult to see a genuine distinction. The fact that the plates themselves weren’t needed for translation suggests they served as props to legitimize an endeavor that was essentially creative writing presented as divine translation.

Absence of Physical Evidence: Despite decades of aggressive attempts by LDS apologists to manufacture archaeological, linguistic, and genetic corroboration—including the heavily promoted “Nahom altars,” claims of “reformed Egyptian,” and creative reinterpretations of DNA evidence through “limited geography” models—not one shred of credible physical evidence supports the Book of Mormon’s historical claims that has been accepted by mainstream scientific communities. The complete absence of evidence for a civilization allegedly comprising millions of people with advanced technology, metallurgy, and writing systems remains inexplicable if the narrative is historical, regardless of apologetic efforts to spin ambiguous archaeological parallels into “mounting evidence”.