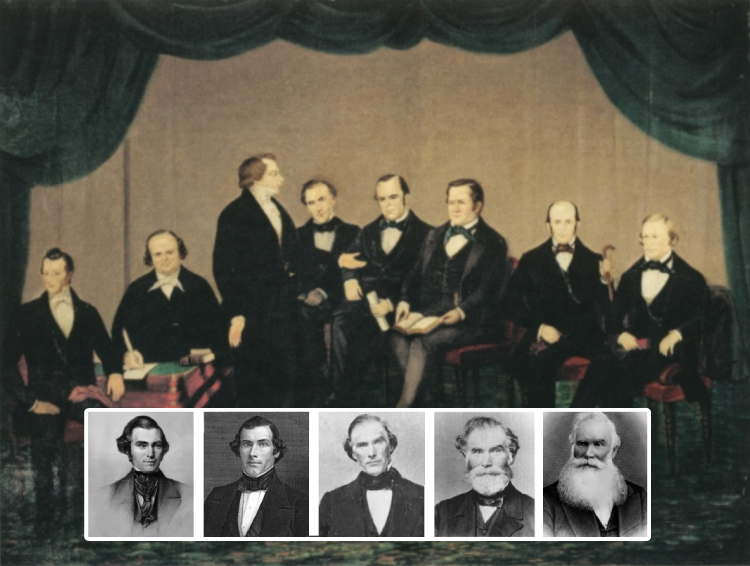

Photo: A collage: Joseph Smith addressing members of the quorum of the twelve. Hyrum Smith, Willard Richards, Joseph Smith, Orson Pratt, Parley P. Pratt, Orson Hyde, Heber C. Kimball, Brigham Young, c. 1843 – 1844. Artworks in the Celestial Room of the First Nauvoo Temple. JSTOR.org. Brigham Young University Studies (2002). Via Wikimedia, Public Domain.

Inset: Orson Pratt over the years.

A Theological and Historical Examination.

Introduction: A Claim Worth Examining

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints makes a remarkable assertion on its official website regarding its Quorum of the Twelve Apostles:

“Jesus Christ calls Apostles to represent Him in our day just as He did in the Bible. They leave behind their regular work lives and devote their life to full-time Church service.”

— The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Official Website

This claim invites scrutiny. If modern LDS apostles truly represent Christ “just as” the New Testament apostles did, we should expect to find substantial parallels between the two groups—in their qualifications, their character, their mission, their unity, and the nature of their authority. The lives of the original Twelve provide a template against which any subsequent claim to apostleship must be measured.

The case of Orson Pratt (1811–1881), one of the original members of the LDS Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, offers a particularly instructive lens through which to examine this claim. Pratt’s nearly fifty-year career as a Mormon apostle was marked by public theological disputes with his church’s president, excommunication and reinstatement, a near-suicide attempt, political maneuvering that stripped him of his seniority, and doctrinal positions that were formally condemned by his own quorum—many of which were later vindicated and adopted by the twentieth-century church.

The question is not whether Pratt was intelligent or influential—by all accounts, he was both. The question is whether his tumultuous apostolic career bears any meaningful resemblance to the apostleship described in the New Testament. And if it does not, what does that tell us about the LDS claim to represent a restoration of biblical Christianity?

Part One: The Biblical Standard—What Made a Man an Apostle?

Before examining Orson Pratt’s career, we must establish what Scripture teaches about apostolic qualifications. This is not a matter of sectarian interpretation but of careful biblical exegesis.

The Criteria Established in Acts 1

When Judas Iscariot betrayed Christ and subsequently took his own life, the remaining eleven apostles gathered to select a replacement. Peter articulated the criteria for this selection in unmistakable terms:

“Therefore it is necessary to choose one of the men who have been with us the whole time the Lord Jesus was living among us, beginning from John’s baptism to the time when Jesus was taken up from us. For one of these must become a witness with us of his resurrection.”

— Acts 1:21-22

Peter’s words establish three non-negotiable qualifications for apostleship:

First, personal accompaniment with Jesus throughout His earthly ministry. The candidate must have been present “the whole time the Lord Jesus was living among us.” This was not a matter of receiving second-hand testimony but of direct, sustained, personal experience with the incarnate Christ.

Second, eyewitness testimony spanning from John’s baptism to the Ascension. The apostle must have been present at the defining moments of Jesus’ public ministry—His baptism, His teachings, His miracles, His crucifixion, and His resurrection appearances.

Third, direct witness of the resurrection. This was the central qualification. The apostles were, above all else, witnesses to the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ. Their authority rested not on institutional appointment but on their firsthand experience of the risen Lord.

As biblical scholar R.C. Sproul observed at Ligonier Ministries:

“Acts 1:21–22 states that for a man to be an apostle, he had to have been a member of the band of disciples from the beginning, and to have been an eyewitness of Christ’s resurrection.”

— Ligonier Ministries, “What Was an Apostle?”

The Apostle Paul: The Exception That Proves the Rule

Some might object that the Apostle Paul did not meet these criteria, having never accompanied Jesus during His earthly ministry. But Paul’s case actually reinforces the standard rather than undermining it.

Paul was explicit that his apostleship was exceptional—he called himself “one untimely born” (1 Corinthians 15:8). His claim to apostleship rested on his direct, personal encounter with the risen Christ on the Damascus road (Acts 9:1-9). In defending his apostolic authority, Paul did not appeal to institutional appointment but to his personal encounter with Jesus:

“Am I not an apostle? Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?”

— 1 Corinthians 9:1

As G3 Ministries notes in their examination of apostolic qualifications:

“Paul defended his apostleship on the very basis of the qualification that he had personally seen the resurrected Christ.”

— G3 Ministries, “What Is An Apostle?”

Paul’s encounter with Christ was not a mystical experience or a spiritual impression—it was a direct confrontation with the physically risen Jesus, who spoke audibly to him and commissioned him for ministry. The other apostles recognized Paul’s apostleship precisely because his experience met the essential criterion: he had seen the risen Lord.

The Foundational Nature of Apostolic Office

The New Testament makes clear that apostleship was not an ongoing office to be perpetuated through institutional succession but a foundational ministry given once for the establishment of the Church:

“Built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone.”

— Ephesians 2:20

Foundations are laid once. You do not keep laying the foundation of a building after it has been constructed. The apostles’ role was to establish the Church, to bear witness to the resurrection, and to receive and transmit the authoritative teaching of Christ. Once this foundation was laid and the New Testament Scriptures were complete, the foundational office was no longer necessary.

As GotQuestions.org explains:

“No biblical evidence exists to indicate that these thirteen apostles were replaced when they died. See Acts 12:1–2, for example. Jesus appointed the apostles to do the founding work of the Church, and foundations only need to be laid once. After the apostles’ deaths, other offices besides apostleship, not requiring an eyewitness relationship with Jesus, would carry on the work.”

— GotQuestions.org, “What Are the Biblical Qualifications for Apostleship?”

When the Apostle James was martyred by Herod (Acts 12:1-2), there is no record of the church selecting a replacement. Why? Because James had fulfilled his apostolic calling, and the church continued without seeking to perpetuate the foundational office.

Part Two: The Troubled Career of Orson Pratt

Against this biblical backdrop, let us examine the apostolic career of Orson Pratt—one of the original members of the LDS Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and, by scholarly consensus, one of the most influential intellectuals in Mormon history.

The Making of a Mormon Apostle

Orson Pratt was born September 19, 1811, in Hartford, New York. His older brother Parley introduced him to Mormonism, and Orson was baptized on his nineteenth birthday in 1830—the same year Joseph Smith founded the Church of Christ (later renamed the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints).

In 1835, at age twenty-three, Pratt was appointed to the original Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. Two years later, he married Sarah Marinda Bates. By all accounts, Pratt was brilliant—a self-taught mathematician, astronomer, and theologian whose intellectual gifts would shape Mormon doctrine for generations.

T. Edgar Lyon, in his 1932 master’s thesis at the University of Chicago, concluded:

“Orson Pratt did more to formulate the Mormons’ idea of God, the religious basis of polygamy, the pre-existence of spirits, the doctrine of the gathering of Israel, the resurrection, and eternal salvation than any other person in the Church, with the exception of Joseph Smith.”

— T. Edgar Lyon, “Orson Pratt—Early Mormon Leader” (M.A. thesis, University of Chicago, 1932)

When Leonard J. Arrington surveyed fifty Mormon scholars in 1969 to identify the most eminent intellectuals in LDS history, Pratt ranked second, ahead of Joseph Smith himself.

But Pratt’s brilliance was matched by controversy. His apostolic career was marked by crises that bear no resemblance to anything we find in the New Testament.

The 1842 Crisis: Excommunication, Suicide Attempt, and Reinstatement

The first major crisis in Pratt’s apostolic career erupted in 1842, during the Nauvoo period—less than a decade after he was appointed an apostle.

While Orson was serving a mission in England (August 1839 – July 1841), Joseph Smith had begun practicing plural marriage. According to multiple accounts, Smith approached Orson’s wife, Sarah, with a proposal to become one of his “spiritual wives.” Sarah later claimed that Smith told her, “The Lord has given you to me as one of my spiritual wives.”

When Orson returned from England and learned of these allegations, he was caught between two impossible positions: believing his wife meant believing his prophet had attempted to seduce her; believing his prophet meant believing his wife had committed adultery or was lying.

The result was catastrophic. In July 1842, Orson disappeared. As Ebenezer Robinson later recalled:

“Under these circumstances his mind temporarily gave way, and he wandered away, no one knew where…. He was found some five miles below Nauvoo, sitting on a rock on the bank of the Mississippi River, without a hat.”

— Ebenezer Robinson, “Items of Personal History of the Editor,” The Return, Vol. 2, No. 11 (November 1890)

Joseph Smith himself recorded the crisis in his journal:

“This A.M. early a report was in circulation that [Orson Pratt] was missing. A letter of his writing was found directed to his wife stating to the effect that he was going away; Soon as this was known Joseph summoned the principal men of the city and workmen on the Temple to meet at the Temple Grove where he ordered them to proceed immediately throughout the city in search of him lest he should have laid violent hands on himself.”

— Joseph Smith Journal, July 15, 1842

A suicide note was found. Orson wrote:

“I am a ruined man! My future prospects are blasted! The testimony upon both sides seems to be equal: the one in direct contradiction to the other—how to decide I know not neither does it matter. For let it be either way my temporal happiness is gone in this world.”

— B.H. Roberts Foundation Primary Source Document

After Orson was found and returned to Nauvoo, he refused to support a public resolution defending Joseph Smith’s character. When Smith asked him directly, “Have you personally a knowledge of any immoral act in me toward the female sex, or in any other way?”, Pratt answered no—but he remained estranged from the church and its founder.

On August 20, 1842, Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and George A. Smith excommunicated Orson Pratt for “insubordination.” His wife, Sarah, was excommunicated for “adultery.”

Here we must pause and ask: Is there any parallel to this in the New Testament? Did any of the original Twelve experience excommunication? Did any face accusations that their leader had attempted to seduce their wife? Did any write suicide notes and wander off to die?

The answer, obviously, is no. The New Testament apostles faced persecution, imprisonment, and martyrdom—but always from outside the church. They were not excommunicated by their own “quorums” for refusing to publicly defend their leader against charges of sexual impropriety.

Reinstatement: But at What Cost?

Pratt was reinstated to the church and the Quorum of the Twelve on January 20, 1843—five months after his excommunication. The circumstances of this reinstatement are instructive.

According to LDS sources, Pratt brought a letter to Joseph Smith that John C. Bennett had written, seeking Pratt’s help in exposing Mormonism. Instead of cooperating with Bennett, Pratt showed the letter to Smith. This “show of loyalty” was apparently sufficient to restore their relationship.

Joseph Smith used an interesting argument for Pratt’s reinstatement: he declared that the August 1842 excommunication had been “illegal” because it lacked a majority of the Quorum. As the Utah History Encyclopedia notes:

“When Orson later received a letter from one of Joseph Smith’s detractors seeking to enlist his support, Pratt took the letter to Smith. This show of loyalty restored their friendship, and on 20 January 1843 church leaders declared Pratt’s excommunication illegal, reinstated him in the church, and reappointed him as an apostle.”

— Utah History Encyclopedia, “Pratt, Orson”

But the matter was not truly resolved. Smith reportedly told Pratt that Sarah had lied about him and suggested Orson divorce her and start a new family. Orson did not divorce Sarah—at least not then. But the seeds of future conflict had been planted.

What are we to make of a religious system in which an “apostle” is excommunicated, reinstated on a legal technicality, told to divorce his wife because she “lied” about the prophet, yet whose wife maintains her testimony against that prophet for the next forty-six years?

Decades of Conflict with Brigham Young

If the 1842 crisis was the beginning of Pratt’s troubles, the decades that followed saw even more remarkable conflicts—not with outsiders but with his own church president.

After Joseph Smith’s assassination in 1844, Pratt supported Brigham Young’s leadership. But the two men held fundamentally incompatible views on critical theological questions, and their disagreements erupted repeatedly in the quorum.

The most significant conflict concerned the nature of God. Brigham Young developed what became known as the “Adam-God doctrine“—the teaching that Adam was actually God the Father in mortal form, the literal father of Jesus Christ’s spirit, and the deity to whom Latter-day Saints should direct their worship.

Orson Pratt flatly rejected this teaching. He believed in a more traditional, literal reading of Mormon scriptures regarding the nature of God. The conflict between the two men was not subtle or private—it played out in quorum meetings, in public sermons, and in written exchanges over more than twenty years.

Gary James Bergera, who has studied this conflict exhaustively, describes the tension:

“Not infrequently, these two strong-willed, deeply religious men argued. Part of their difficulty was that they saw the world from opposing perspectives—Pratt’s a rational, independent-minded stance and Young’s a more intuitive and authoritarian position.”

— Signature Books, Conflict in the Quorum

Young was not subtle in his criticism of Pratt. In quorum meetings, he called Pratt’s ideas “false as hell” and warned that “if he did not take a different course in his Philosophy & order of reasoning, he would not stay long in this Church.”

Heber C. Kimball, one of Young’s counselors, complained:

“Brother Orson Pratt has withstood Joseph [Smith] and he has withstood Brother Brigham [Young] many times and he has done it tonight and it made my blood chill. It is not for you to lead [the prophet], but to be led by him. You have not the power to dictate but [only] to be dictated [to].”

— Quoted in Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum

Apostle Wilford Woodruff recorded in his journal:

“Elder Orson Pratt pursued a Course of Stubbornness & unbelief in what President Young said that will destroy him if he does not repent & turn away from his evil way. For when any man crosses the track of a leader in Israel & tryes to lead the prophet, he is no longer lead by him but is in danger of falling.”

— Wilford Woodruff Journal, as quoted in Mormonism Research Ministry

Yet Pratt refused to capitulate. In one heated exchange, he declared:

“I am not a man to make a confession of what I do not believe. I am not going to crawl to Brigham Young and act the hypocrite. I will be a free man. It may cost me my fellowship, but I will stick to it. If I die tonight, I would say, O Lord God Almighty, I believe what I say.”

— Quoted in Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum

Young’s response was characteristically blunt: “You have been a mad stubborn mule. [You] have taken a false position…. It is [as] false as hell and you will not hear the last of it soon.”

The 1865 Official Condemnation

The tensions finally produced an official action. In 1865, a majority of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles officially condemned some of Pratt’s doctrinal writings—including portions of The Seer, the periodical he had published in the 1850s at Young’s request to defend polygamy.

This was extraordinary. An apostle’s published theological works—works that had been produced at the church president’s request—were formally repudiated by the quorum as “misleading and questionable in relation to the actual doctrine of the Church.”

As the Wikipedia entry on Orson Pratt summarizes:

“In 1865, a majority of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the LDS Church officially condemned some of Pratt’s doctrinal writings, including some of his articles from The Seer. They considered it to be misleading and questionable in relation to the actual doctrine of the Church.”

— Wikipedia, “Orson Pratt”

Again, we must ask: Is there any New Testament parallel to this? Did Peter ever have his epistles condemned by the other apostles? Did James repudiate Paul’s letters? Did the Jerusalem Council issue a formal condemnation of any apostle’s theological writings?

The answer, again, is no. The New Testament apostles disagreed—Paul famously confronted Peter “to his face” over the question of eating with Gentiles (Galatians 2:11)—but they did not formally condemn one another’s doctrinal writings. They resolved their differences through the Jerusalem Council described in Acts 15, arriving at a unified position that “seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us” (Acts 15:28).

The 1875 Demotion: Political Maneuvering to Prevent Succession

The final blow to Pratt’s apostolic standing came in 1875, when Brigham Young participated in what can only be described as political maneuvering to ensure that Pratt would never become church president.

Under LDS succession rules, the senior member of the Quorum of the Twelve becomes church president upon the death of the incumbent. By 1875, Pratt was second in seniority among the apostles—meaning he would likely become president if he outlived Young.

Young resolved this problem by retroactively applying a rule about seniority. He declared that because Pratt had been excommunicated in 1842 (the excommunication that had been declared “illegal” at the time of his reinstatement), his seniority should be dated from his reinstatement rather than his original ordination. This moved Pratt from second to fourth in seniority, ensuring that John Taylor—not Pratt—would succeed Young as church president.

As Gary James Bergera explains:

“Why was Pratt demoted in 1875? Put simply, ranking church leaders—Brigham Young, George A. Smith—did not want him to become president. This was because of Pratt’s reluctance to side with Joseph Smith in Nauvoo as well as his protracted doctrinal disagreements with Young.”

— Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum, p. 280

The Mormonism Research Ministry review of Bergera’s book summarizes:

“Young ended up having the last laugh. Because there was an assumption that Pratt had been excommunicated in 1842—even though Bergera insists that this never officially happened—Young participated in some legal maneuvering in 1875 and demoted the seniority status for both Orson Hyde and Orson Pratt, moving John Taylor ahead of both of them and allowing him to become Young’s successor in 1877.”

— Mormonism Research Ministry, Review of Conflict in the Quorum

This is ecclesiastical politics of the most cynical sort. And yet, remarkably, Young refused to excommunicate Pratt for his theological disagreements—“an indication,” as Wikipedia notes, “of how Young was willing to tolerate differences of opinion on theological issues.”

But “tolerate” is the wrong word. Young was willing to condemn Pratt’s writings, demote his seniority, and prevent him from ever leading the church—but he would not remove him from the quorum entirely. Why? Perhaps because Pratt was too valuable an intellectual asset. Perhaps because excommunicating him would have created a larger scandal. Perhaps because Young recognized that Pratt’s “stubbornness” reflected genuine conviction rather than rebellion.

Whatever the reason, the result was a fifty-year apostolic career marked by scandal, suicide attempts, excommunication, reinstatement, decades of public theological conflict, official condemnation, and political demotion. Is this what the New Testament means by apostleship?

The Ironic Vindication

The final irony of Orson Pratt’s career is that history vindicated him rather than Brigham Young.

After Young died in 1877, Pratt’s theological positions gradually gained acceptance within the LDS Church. The Adam-God doctrine—the teaching at the heart of the Pratt-Young conflict—declined in official espousal and is today considered heretical by the mainstream LDS Church. Members who embrace it “become liable to official church censure.”

As Bergera notes:

“The positions Brigham Young officially censured Pratt for holding ended up winning out in the twentieth-century LDS Church. Bergera notes that ‘several of Pratt’s unpopular ideas have now found acceptance among such influential twentieth century church exegetes as Joseph Fielding Smith,’ whose insistence that ‘God knows all things’ and that ‘his understanding is perfect, not “relative”‘ echoes what Pratt had argued all along.”

— Bergera, “The Orson Pratt–Brigham Young Controversies,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 13, no. 2 (Summer 1980)

Bruce R. McConkie’s influential Mormon Doctrine “shows a kindred debt to Pratt’s theories in his sections on ‘God,’ the ‘Godhead,’ and ‘Eternal Progression,'” and Bergera concludes that “reliance on Pratt is strong and surprising.”

Pratt was also vindicated on other points of contention with Young. The LDS Church’s 1979 inclusion of Joseph Smith’s biblical changes in its King James edition “effectively lay to rest any reservations about Smith’s work”—just as Pratt had wanted. And “later research has largely vindicated Lucy Mack Smith’s book,” which Young had ordered destroyed.

Bergera sums up the long arc of their rivalry:

“The rhetorical, logical, and scriptural power of Pratt’s arguments would not die out completely and eventually experienced a renaissance. As sometimes occurs over time, the boundaries separating both men’s positions have since become blurred, and ultimate victory—so often pyrrhic—a matter of perspective.”

— Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum, p. 280

So Orson Pratt was right—and Brigham Young was wrong. The apostle was vindicated, and the prophet’s teachings were repudiated.

But this raises an even more troubling question: How can both men have held genuine apostolic authority if their teachings on fundamental questions about the nature of God were irreconcilably opposed? If Young was a prophet receiving revelation from God, how could his Adam-God doctrine be heretical? If Pratt was an apostle receiving revelation from God, how could his writings be officially condemned?

The New Testament provides no parallel to this kind of theological chaos among the apostles.

Part Three: The New Testament Contrast—Unity in Essentials

The contrast between Orson Pratt’s apostolic career and the New Testament pattern could hardly be more stark. Let us examine what Scripture reveals about how the original apostles handled disagreement.

The Jerusalem Council: A Model of Apostolic Unity

The most significant theological dispute in the early church was the question of Gentile inclusion: Must Gentile converts be circumcised and observe the Mosaic Law to be saved? This was not a minor question—it struck at the heart of the gospel itself.

Acts 15 records how the apostles addressed this crisis. Paul and Barnabas traveled to Jerusalem to meet with Peter, James, John, and the other elders. There was “much debate” (Acts 15:7). Different perspectives were expressed. Peter testified to his experience with Cornelius; Paul and Barnabas reported on God’s work among the Gentiles.

Then James offered a proposal, grounded in Scripture (quoting Amos 9:11-12), that formed the basis for the council’s decision. The result was a letter declaring that “it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us” to impose no burden on Gentile believers except for certain basic moral requirements (Acts 15:28-29).

Notice what did not happen at the Jerusalem Council:

• No apostle was excommunicated for holding an opposing view

• No apostle wrote a suicide note in despair

• No apostle’s writings were formally condemned

• No apostle was demoted in seniority to prevent him from leading

• No apostle was accused of attempting to seduce another apostle’s wife

The apostles disagreed, debated, and reached a Spirit-led consensus. Their unity was not uniformity—it was agreement on essentials arrived at through prayer, Scripture, and mutual submission.

As Britannica notes:

“The Council of Jerusalem thus demonstrated the willingness of apostolic leaders to make compromises on certain secondary issues in order to maintain peace and unity in the church.”

— Britannica, “Council of Jerusalem”

Paul and Peter: Confrontation Without Condemnation

As briefly mention above, the most famous disagreement between apostles is Paul’s confrontation with Peter at Antioch (Galatians 2:11-14). Peter had been eating with Gentile believers but withdrew when certain men came from James, fearing the criticism of the “circumcision party.”

Paul confronted Peter publicly: “I opposed him to his face, because he stood condemned” (Galatians 2:11). This was not a minor rebuke—Paul accused Peter of hypocrisy and of not acting “in line with the truth of the gospel” (Galatians 2:14).

But notice the outcome. There is no record of Peter being excommunicated. There is no record of Paul’s letters being condemned. There is no record of Peter’s seniority being adjusted to prevent him from leading. The confrontation produced correction, not schism.

Peter himself later acknowledged Paul’s authority, writing:

“Bear in mind that our Lord’s patience means salvation, just as our dear brother Paul also wrote you with the wisdom that God gave him. He writes the same way in all his letters, speaking in them of these matters. His letters contain some things that are hard to understand, which ignorant and unstable people distort, as they do the other Scriptures, to their own destruction.”

— 2 Peter 3:15-16

Peter called Paul’s writings “Scripture.” This is the opposite of formal condemnation. This is recognition of divine authority.

The Apostles and False Teachers

The New Testament apostles were fierce in their condemnation of false teachers—but they recognized that the danger came from outside the apostolic circle, not from within it.

Peter warned of “false prophets” and “false teachers” who would arise “among you” (2 Peter 2:1). Paul warned the Ephesian elders that “savage wolves will come in among you and will not spare the flock” (Acts 20:29). John warned of those who “went out from us, but they did not really belong to us” (1 John 2:19).

The apostles presented a united front against error. They did not spend decades publicly disagreeing with one another about the nature of God. They did not write pamphlets defending opposing theological positions. They did not engage in political maneuvering to prevent one another from leading.

As the North American Mission Board explains in its analysis of LDS apostolic claims:

“Neither Paul nor the other apostles make any provision here or anywhere else in the New Testament for a succession of apostles or prophets to lead the church from the top down. The apostasy that was coming would not be a complete apostasy because of a lack of supposedly essential prophets, but would instead be a partial apostasy, a falling away of some (as Paul says explicitly) because they paid attention to prophets inspired by ‘deceitful spirits’ or ‘demons’ (1 Tim. 4:1).”

— NAMB, “LDS Apostles and Prophets: What Did the New Testament Apostles Say?”

Part Four: The “Great Apostasy” Claim—A Necessary Fiction?

The LDS Church claims that its restoration of apostles and prophets was necessary because of a “Great Apostasy” that occurred after the death of the original apostles. This doctrine is essential to Mormon ecclesiology: if the church established by Jesus never failed, there would be no need for Joseph Smith to “restore” it.

But the Great Apostasy claim creates more problems than it solves—particularly when examined in light of the turmoil that characterized the LDS Quorum of the Twelve from its earliest years.

The LDS Position

According to official LDS teaching:

“Following the death of Jesus Christ, wicked people persecuted and killed many Church members. Other Church members drifted from the principles taught by Jesus Christ and His Apostles. The Apostles were killed, and priesthood authority—including the keys to direct and receive revelation for the Church—was taken from the earth. Because the Church was no longer led by priesthood authority, error crept into Church teachings.”

— The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “The Great Apostasy”

The implication is clear: the true church requires living apostles with proper priesthood authority. When the apostles died, the church collapsed into error. Only through Joseph Smith’s restoration could true Christianity be recovered.

M. Russell Ballard, senior LDS apostle, stated:

“We’re not Catholic and we’re not Protestant, but we are the New Testament Church that’s been restored because we believe it was lost after the times of Christ and his apostles and was required to be restored through a prophet.”

— M. Russell Ballard, quoted in “Elder Ballard Responds to Evangelical Criticism,” Deseret News, December 6, 2007

The Problem with the Claim

But if the church requires apostles with proper priesthood authority to prevent it from falling into error, how do we explain the errors that characterized the LDS apostolate from its earliest years?

Consider: The LDS Quorum of the Twelve, supposedly holding the same “keys” and “authority” as the original apostles, was unable to prevent:

• Its own president (Brigham Young) from teaching heretical doctrine (Adam-God) for decades

• One of its own members (Orson Pratt) from being excommunicated, near-suicidal, and reinstated

• Decades of public theological conflict between its president and its leading intellectual

• The formal condemnation of an apostle’s published doctrinal writings

• Political maneuvering to prevent an apostle from leading the church

If the presence of living apostles with priesthood authority prevents doctrinal error, why was there so much doctrinal error among the LDS apostles? If the Great Apostasy occurred because the church lacked apostolic leadership, what do we call a church whose apostles spend decades publicly contradicting one another about the nature of God?

As the NAMB analysis notes:

“In Peter’s last instructions to the church, he warned that just as false prophets arose among the people in the past, false teachers would arise among the believers (2 Pet. 2:1). Peter says nothing about the church languishing into a general apostasy because of a lack of apostles or prophets. Nor does he suggest that the church will cease to exist.”

— NAMB, “LDS Apostles and Prophets: What Did the New Testament Apostles Say?”

Jesus’ Promise to His Church

The New Testament presents a very different picture of the church’s durability. Jesus Himself promised:

“I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it.”

— Matthew 16:18

This is not a promise that the church would be protected from persecution, suffering, or even the deaths of its leaders. It is a promise that the church itself would never be destroyed. The gates of Hades—death itself—would not prevail against it.

If Jesus’ promise is true, there was no Great Apostasy. The church He founded has continued, imperfectly but genuinely, from Pentecost to the present day. Individual members and even leaders have fallen into error, but the church itself has never ceased to exist.

This understanding aligns with Peter’s final instructions to the church:

“Dear friends, since you have been forewarned, be on your guard so that you may not be carried away by the error of the lawless and fall from your secure position. But grow in the grace and knowledge of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.”

— 2 Peter 3:17-18

Peter presupposes that “dear friends” will continue following the apostolic teaching until Christ’s return. He encourages them to “grow in the grace and knowledge” of Christ—not to await a future prophet who will restore what has been lost.

Part Five: What Does “Representing Christ” Actually Mean?

The LDS Church claims that its apostles “represent Christ just as He did in the Bible.” But the career of Orson Pratt—and the broader pattern of conflict within the LDS Quorum of the Twelve—reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of what New Testament apostleship actually entailed.

The Apostles as Eyewitnesses, Not Administrators

The New Testament apostles were, first and foremost, eyewitnesses of the risen Christ. Their authority derived not from institutional appointment but from their direct experience with Jesus—His teaching, His miracles, His death, and His resurrection.

When Peter preached at Pentecost, he declared:

“This Jesus God raised up, and of that we all are witnesses.”

— Acts 2:32

When Paul defended his apostleship, he asked:

“Am I not an apostle? Have I not seen Jesus our Lord?”

— 1 Corinthians 9:1

The apostles’ message was not philosophical speculation or institutional tradition—it was testimony. “That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked at and our hands have touched—this we proclaim” (1 John 1:1).

LDS apostles cannot make this claim. They have not seen the risen Christ with their physical eyes. They have not touched His wounds. They have not eaten breakfast with Him on the shore of Galilee. Whatever spiritual experiences they may have had, they lack the foundational qualification that defined New Testament apostleship.

The Apostles as Foundation-Layers, Not Perpetual Officers

The New Testament presents apostleship as a foundational office, not a perpetual one. Paul writes that the church is “built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Christ Jesus himself as the chief cornerstone” (Ephesians 2:20).

A foundation is laid once. It does not need to be laid again in every generation. The apostles’ unique role was to establish the church, to bear witness to the resurrection, and to receive and transmit the authoritative teaching of Christ that would be preserved in the New Testament Scriptures.

This is why there is no record of the apostles being replaced after their deaths (except for Judas, who abandoned his post by betrayal and suicide). When James, the son of Zebede,e was martyred (Acts 12:2), no replacement was selected. The foundational work was being completed, and the church would continue under the ongoing ministry of elders, pastors, and teachers—not under perpetual apostolic succession.

The Apostles as Unified Witnesses, Not Competing Theologians

Perhaps most significantly, the New Testament apostles presented a unified testimony. They disagreed on secondary matters, but they were united on the essentials of the gospel—the deity of Christ, His atoning death, His bodily resurrection, and salvation by grace through faith.

The contrast with Orson Pratt’s career could not be more stark. Pratt spent decades publicly disagreeing with his church president about the nature of God—not a secondary matter, but the most fundamental question of theology. His writings were condemned by his own quorum. His theological legacy was eventually vindicated, meaning that his president’s teachings were eventually repudiated as heretical.

This is not how the New Testament apostles operated. When they gathered at the Jerusalem Council, they reached a unified decision that “seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us” (Acts 15:28). They did not publish competing pamphlets. They did not engage in decades of public theological conflict. They did not use political maneuvering to prevent one another from leading.

Part Six: The Theological Chaos of the Pratt-Young Dispute

To fully appreciate the contrast between New Testament apostleship and the LDS version, we must examine the substance of the theological disputes that consumed Orson Pratt and Brigham Young for more than two decades. These were not minor disagreements about secondary matters—they concerned the very nature of God.

The Adam-God Controversy

Brigham Young’s most controversial teaching was what has come to be known as the “Adam-God doctrine.” In an 1852 general conference address, Young declared that Adam was not merely the first man but was actually God the Father Himself, who had come to earth in mortal form to begin the human race. It further implied that Adam/God was the literal father of Jesus Christ’s spirit body.

Orson Pratt found this doctrine incomprehensible and unscriptural. He believed that the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost were three distinct personages—not that the Father had once been a mortal man named Adam who lived in the Garden of Eden. Pratt’s understanding aligned more closely with what would become mainstream LDS theology in the twentieth century.

The conflict between these two views was not merely academic. It concerned the most fundamental question in all of theology: Who is God? If the president of the church and one of his leading apostles could not agree on who God is, what does that say about the reliability of their claimed prophetic and apostolic authority?

The Question of God’s Omniscience

A related dispute concerned whether God is truly omniscient—whether He knows all things past, present, and future. Brigham Young taught that God continues to progress in knowledge, learning new things throughout eternity. Orson Pratt insisted that God’s knowledge is complete and perfect—that He knows all things and does not learn or progress in understanding.

This may seem like a philosophical technicality, but it has profound implications for the nature of prophecy, the reliability of revelation, and the character of the God whom Mormons worship. If God is still learning, can His revelations be trusted as absolutely true? If God does not yet know everything, how can He reliably guide His church?

Again, Pratt’s position eventually won out. Joseph Fielding Smith, the tenth LDS president, insisted that “God knows all things” and that “his understanding is perfect, not ‘relative.'” This was precisely what Pratt had argued, and precisely what Young had condemned.

The Publication of The Seer

One of the ironies of the Pratt-Young conflict is that Pratt was originally assigned by Young to publish The Seer as a defense of polygamy. Beginning in 1853, Pratt produced a twelve-month series explaining and defending the practice of plural marriage with theological and scriptural arguments.

But Pratt, being Pratt, could not resist incorporating his broader theological views into the publication. His explanations of God, the Godhead, and eternal progression reflected his own systematic thinking rather than Young’s more intuitive and less consistent approach.

When Young later realized that Pratt’s publications contained theological positions with which he disagreed, he was furious. The very publications that Young had commissioned became evidence for the condemnation of Pratt’s teachings. This is a pattern we see repeatedly in the Pratt-Young relationship: Young would assign Pratt a task, Pratt would complete it according to his own theological understanding, and Young would later condemn the result.

Parallel Controversies in LDS History

The Pratt-Young controversy was not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern of theological disputes within LDS leadership. Consider some parallel examples:

The 1978 Revelation on Priesthood: For more than a century, the LDS Church denied priesthood ordination to men of African descent. Brigham Young had taught that this restriction was divinely mandated and would continue until the end of the millennium. In 1978, under President Spencer W. Kimball, the church reversed this policy entirely.

Plural Marriage: Joseph Smith secretly practiced plural marriage; Brigham Young publicly defended it as an essential doctrine for exaltation. In 1890, under President Wilford Woodruff, the church officially abandoned the practice—though it continued secretly for years afterward. Today, the LDS Church excommunicates members who practice polygamy.

Blood Atonement: Brigham Young taught that certain sins were so serious that the blood of Jesus Christ could not atone for them—only the shedding of the sinner’s own blood could provide redemption. This doctrine has been quietly abandoned and is now rejected by mainstream Mormonism.

Each of these reversals raises the same question that the Pratt-Young controversy raises: If prophets and apostles can be so dramatically wrong about fundamental doctrines, what is the value of their prophetic and apostolic authority? The New Testament apostles did not teach doctrines that later apostles would condemn as heresy.

Part Seven: Sarah Pratt—The Woman at the Center

No examination of Orson Pratt’s apostolic career is complete without considering the woman whose testimony placed him in an impossible position: his first wife, Sarah Marinda Bates Pratt.

Sarah’s Account

Sarah consistently maintained throughout her life that Joseph Smith had approached her with a proposal of plural marriage while Orson was serving a mission in England. According to Sarah, Smith told her that “the Lord has given you to me as one of my spiritual wives.” She claimed to have rejected his advances and to have been subsequently slandered by church leaders as an adulteress.

The official LDS position was that Sarah had actually committed adultery with John C. Bennett, the excommunicated former mayor of Nauvoo who had become one of Joseph Smith’s most vocal critics. Affidavits were produced claiming to support this version of events—affidavits that Sarah later claimed were coerced or fabricated.

The Impossible Choice

Orson Pratt was caught between two accounts that could not both be true. Either his wife was telling the truth—which meant his prophet had attempted to seduce her—or his prophet was telling the truth—which meant his wife was an adulteress and a liar.

The documentary evidence from the period shows Orson vacillating between these positions. His suicide note expresses the impossibility of his situation:

“The testimony upon both sides seems to be equal: the one in direct contradiction to the other—how to decide I know not neither does it matter for let it be either way my temporal happiness is gone in this world.”

This is not the language of a man confidently exercising apostolic discernment. This is the language of a man in despair, unable to determine whether his wife or his prophet is telling the truth about a matter of fundamental importance.

Sarah’s Later Life

After her 1868 divorce from Orson—prompted, according to her, by his “obsession with marrying younger women”—Sarah became one of the most outspoken critics of polygamy in Utah Territory. She helped found the Anti-Polygamy Society of Salt Lake City and gave numerous interviews denouncing the practice.

Her assessment of polygamy was devastating:

“[Polygamy] completely demoralizes good men and makes bad men correspondingly worse. As for the women—well, God help them! First wives it renders desperate, or else heart-broken, mean-spirited creatures.”

Sarah never recanted her testimony about Joseph Smith’s advances. She maintained until she died in 1888 that Smith had propositioned her and that the subsequent accusations of adultery had been fabricated to protect Smith’s reputation.

The Significance of Apostolic Authority

Sarah Pratt’s testimony—and Orson’s anguished inability to determine its truth—raises profound questions about the nature of LDS apostolic authority. If an apostle cannot discern whether his own wife is telling the truth about the prophet’s behavior, how can he claim prophetic insight on matters of doctrine and practice?

The New Testament presents a very different picture. The apostles demonstrated supernatural gifts of discernment—Peter knew that Ananias and Sapphira had lied to the Holy Spirit (Acts 5:1-11); Paul perceived that Elymas was “full of all deceit and fraud” (Acts 13:10). These were men who could see through deception to the truth beneath.

Orson Pratt, by contrast, was reduced to despair by his inability to determine whether his wife or his prophet was lying about adultery and sexual propositions. This is not apostolic discernment. This is an ordinary man in an impossible situation, lacking any supernatural insight that might have resolved his dilemma.

Part Eight: The “Restoration” That Needed Constant Correction

The LDS claim of restored apostleship presupposes that the restoration brought back something that had been lost—pure doctrine, true authority, and reliable prophetic guidance. But the history of the LDS Quorum of the Twelve reveals a pattern of constant correction, reversal, and dispute that bears no resemblance to the New Testament model.

The Pattern of Revision

Consider the pattern that emerges from the Pratt-Young controversy and similar disputes:

• A prophet or apostle teaches a doctrine with confidence and authority

• Another leader disputes or questions that doctrine

• Conflict ensues within the quorum

• Eventually, one position wins out, and the other is abandoned

• The abandoned position is later characterized as personal opinion, speculation, or error

This pattern has repeated itself throughout LDS history. Brigham Young’s Adam-God doctrine was taught with prophetic authority, disputed by Pratt, defended by Young, and eventually abandoned by the church. The priesthood restriction on men of African descent was taught as divine revelation, defended for over a century, and eventually reversed. Blood atonement was preached from the pulpit, then quietly set aside.

The Contrast with New Testament Unity

The New Testament apostles demonstrated remarkable unity on core doctrines—even across different cultural contexts and audiences. Paul, writing to Gentile churches, and James, writing to Jewish believers, both taught justification by faith and the necessity of works that demonstrate genuine faith. Peter, John, and Paul all taught the deity of Christ, His atoning death, His bodily resurrection, and His coming return.

When disputes arose—as they did at the Jerusalem Council—they were resolved through careful deliberation that produced unified teaching. The council’s letter declared that “it seemed good to the Holy Spirit and to us” to impose certain requirements on Gentile believers (Acts 15:28). This was not a compromise between competing theological positions; it was a Spirit-led consensus that the entire apostolic community could affirm.

The LDS Quorum of the Twelve, by contrast, has been marked by decades-long theological disputes in which prophets and apostles contradicted one another on fundamental questions. The “restoration” did not restore apostolic unity; it introduced apostolic conflict on a scale unknown in the New Testament church.

What Kind of Authority?

This raises a fundamental question about the nature of LDS apostolic authority. If apostles can be wrong about the nature of God (as Young was about Adam-God), if prophets can be wrong about who holds the priesthood (as the church was about men of African descent), if the Quorum of the Twelve can formally condemn an apostle’s writings and later adopt his positions as orthodox—what is the value of apostolic authority?

The New Testament presents apostles as authoritative precisely because they are eyewitnesses of Christ and recipients of His direct teaching. Their authority is not institutional; it is testimonial. They teach what they have seen and heard. They transmit what Christ Himself delivered to them.

LDS apostles claim a similar authority but cannot provide similar credentials. They have not seen the risen Christ. They have not received direct teaching from Him. They rely on the testimony of Joseph Smith—whose own claims cannot be independently verified and whose character was disputed even by his closest associates.

And the fruit of their ministry—decades of theological conflict, formal condemnations later reversed, doctrines taught as revelation later abandoned as error—does not inspire confidence in the reliability of their authority.

Conclusion: A Different Kind of Apostleship

The career of Orson Pratt reveals something important about the nature of LDS apostleship. Despite the official claim that LDS apostles “represent Christ just as He did in the Bible,” the actual history tells a very different story.

Pratt was excommunicated and reinstated. He wrote a suicide note in despair over accusations involving his wife and his prophet. He spent decades in public theological conflict with his church president. His writings were formally condemned by his own quorum. His seniority was demoted through political maneuvering to prevent him from leading the church. And in the end, his theological positions were vindicated while his president’s teachings were repudiated as heresy.

This is not what New Testament apostleship looks like.

The original Twelve were eyewitnesses to the risen Christ. They laid the foundation of the church through their testimony and teaching. They reached unified decisions through prayer, Scripture, and mutual submission. They presented a consistent message about the nature of God, the person of Christ, and the way of salvation.

LDS apostles, by contrast, have spent nearly two centuries in theological disputes, institutional power struggles, and doctrinal reversals. They have condemned one another’s teachings and maneuvered to prevent one another from leading. They have taught doctrines (like Adam-God) that were later repudiated as heresy, and they have condemned teachings (like Pratt’s on the nature of God) that were later accepted as orthodox.

The claim that LDS apostles “represent Christ just as He did in the Bible” cannot withstand historical scrutiny. The New Testament apostles were unique—called directly by Christ, eyewitnesses of His resurrection, and commissioned to lay the foundation of His church. That foundation has been laid. It does not need to be laid again.

The church that Christ promised to build—the church that the gates of Hades would not overcome—has continued from Pentecost to the present day. It has weathered persecution, error, and schism. But it has never ceased to exist, and it has never needed to be “restored.”

The enigma of Orson Pratt is not that he was a flawed man—all of us are flawed. The enigma is that his flawed career is presented as an example of biblical apostleship, when it bears no resemblance to what the New Testament actually describes.

Those who seek the authentic faith of the apostles will not find it in nineteenth-century Utah. They will find it where it has always been—in the Scriptures that the apostles themselves gave us, preserved and transmitted through the church that Christ promised would never fail.

“So then you are no longer strangers and aliens, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus himself being the cornerstone, in whom the whole structure, being joined together, grows into a holy temple in the Lord.”

— Ephesians 2:19-21

Sources Consulted

-

Bergera, Gary James. “The Orson Pratt–Brigham Young Controversies: Conflict Within the Quorums, 1853–1868.” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 13, no. 2 (Summer 1980).

-

Bergera, Gary James. Conflict in the Quorum: Orson Pratt, Brigham Young, Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002.

-

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “Quorum of the Twelve Apostles.” Official Website.

-

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “The Great Apostasy.” Official Manual.

-

England, Breck. The Life and Thought of Orson Pratt. 1985.

-

GotQuestions.org. “What Are the Biblical Qualifications for Apostleship?”

-

G3 Ministries. “What Is An Apostle?”

-

Joseph Smith Papers. Journal, December 1841–December 1842.

-

Learn Ligonier. “What Was an Apostle?”

-

Lyon, T. Edgar. “Orson Pratt—Early Mormon Leader.” M.A. thesis, University of Chicago, 1932.

-

Mormonism Research Ministry. Various articles on Orson Pratt and the Great Apostasy.

-

North American Mission Board. “LDS Apostles and Prophets: What Did the New Testament Apostles Say?”

-

Utah History Encyclopedia. “Pratt, Orson.”

-

Wikipedia. “Orson Pratt.”

-

Wikipedia. “Great Apostasy.”

-

Wikipedia. “Council of Jerusalem.”