“

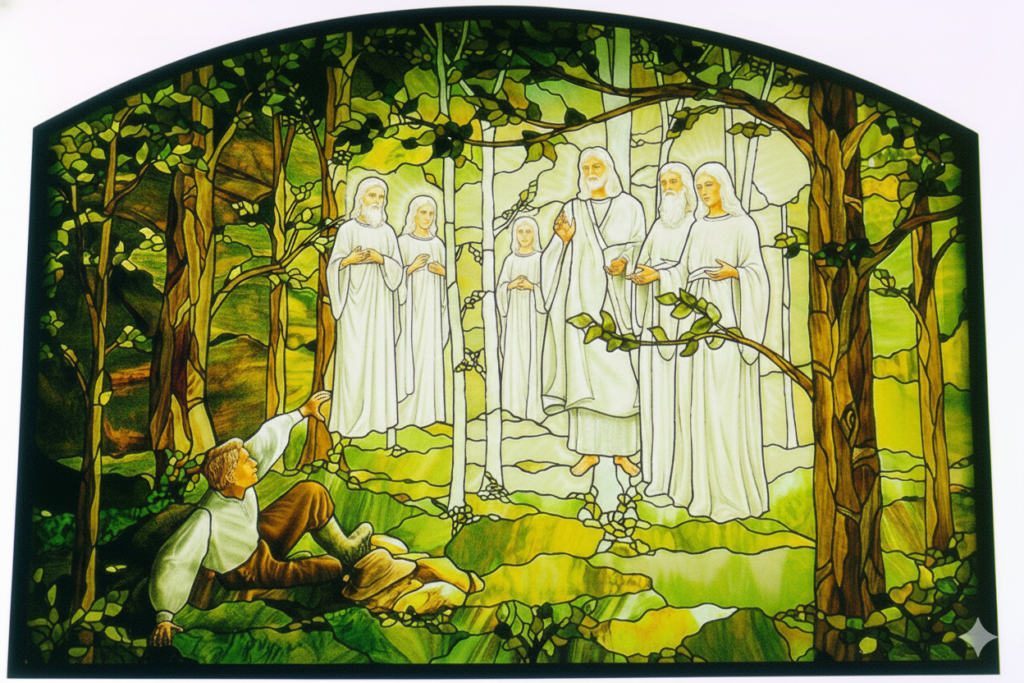

Okay, seriously, how many of you are behind the trees? Is there a shuttle bus?

A Critical Examination of Latter-day Saint Theology on the Book of Mormon

and First Vision from a Comparative Theological Perspective

A Comparative Theological Analysis:

“Are Mormons Christian?” Series

Abstract

This article examines the foundational historical claims of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) regarding two central elements of faith: the Book of Mormon as ancient American scripture and Joseph Smith’s First Vision accounts. Drawing upon primary LDS sources, biblical scholarship, archaeological research, and contemporary critical analyses, this study demonstrates how these claims diverge significantly from historic Christian orthodoxy in their epistemological foundations, historical attestation, and theological implications. While acknowledging the sincerity and communal coherence of LDS historical narratives, this analysis clarifies fundamental differences in doctrines of revelation, scriptural authority, and the grounds of faith between Latter-day Saint teaching and creedal Christianity.

Introduction: The Significance of Historical Claims in Christian Theology

Christianity has always been a profoundly historical religion. From the apostolic witness documented in the New Testament to the creedal affirmations hammered out in the councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon, orthodox Christian faith rests upon specific, testable historical events—supremely the incarnation, crucifixion, and bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ. As the apostle Paul declared, “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins.” (1 Corinthians 15:17, ESV). The Christian gospel is not merely a set of spiritual principles or moral teachings but the proclamation of God’s decisive action within human history.

The Latter-day Saint tradition shares this commitment to historical grounding but extends it in directions that diverge fundamentally from historic Christianity. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) asserts that authentic Christianity was lost through apostasy following the death of the original apostles and was restored through Joseph Smith Jr. beginning in 1820. Central to this restoration narrative are two foundational historical claims: first, that the Book of Mormon represents an authentic ancient record of Israelite peoples who migrated to the Americas circa 600 BC, inscribed on gold plates and translated by Smith through divine means; second, that Smith experienced a theophany—the First Vision—in which God the Father and Jesus Christ appeared to him personally, inaugurating the restoration of the true Church.

These claims are not peripheral to LDS identity but constitute its very foundation. As LDS Apostle Jeffrey R. Holland stated, “The Book of Mormon is the keystone of our religion… Remove the keystone, and the arch crumbles.” Similarly, the First Vision serves as Mormonism’s originating moment, the lens through which all subsequent revelation and authority claims are understood. Without these historical events, the LDS restoration narrative collapses.

This article undertakes a comparative theological analysis of these two foundational LDS historical claims, examining them against the standards of biblical Christianity as understood through Scripture, creedal tradition, and contemporary scholarship. The methodology employed here is neither polemical dismissal nor uncritical acceptance but careful evaluation: presenting LDS theology in its own terms, understanding its internal coherence, and then subjecting its historical and theological claims to rigorous scrutiny informed by biblical exegesis, historical research, and orthodox Christian doctrine. This will hopefully be the theological equivalent of “Wash, rinse, repeat.”

Three central questions organize this investigation: (1) What are the specific historical claims made by the LDS Church regarding the Book of Mormon and the First Vision? (2) How do these claims compare to traditional Christian understandings of Scripture, revelation, and historical attestation? (3) What are the epistemological and soteriological implications of accepting or rejecting these divergent historical foundations? By addressing these questions, this study seeks to provide clarity for Christians engaging with Latter-day Saints in honest theological dialogue, while also offering pastoral guidance for those seeking to understand why historic Christianity cannot accommodate LDS historical claims within its theological framework.

Latter-day Saint Historical Claims: The Book of Mormon and First Vision

The Book of Mormon as Ancient American Scripture

LDS teaching presents the Book of Mormon as “another testament of Jesus Christ,” a divinely inspired record comparable in authority to the Bible itself. According to the official LDS narrative, in approximately 600 BC, a prophet named Lehi was commanded by God to leave Jerusalem with his family before the Babylonian conquest. Lehi’s party journeyed to the Americas, where his descendants—divided into two primary groups, the Nephites and Lamanites—established advanced civilizations. These peoples kept sacred records on metal plates, written in “reformed Egyptian” script, chronicling their history, prophecies, and the post-resurrection appearance of Jesus Christ to them. The final custodian of these records was Mormon, a Nephite prophet-general, who abridged centuries of records onto gold plates around AD 385. His son Moroni added a final testament and buried the plates in a hill (later identified as Cumorah in New York) around AD 421. There they remained until September 21, 1823, when the angel Moroni appeared to Joseph Smith, revealing the location of the plates. Smith received the plates in 1827 and translated them by the “gift and power of God”—primarily using seer stones placed in a hat—producing the English Book of Mormon published in 1830. The response from Star Trek’s Spock, being mildly stimulated by the story, would likely be, “Fascinating!”

The LDS Church emphasizes several elements supporting the Book of Mormon’s authenticity. These include testimony from eleven witnesses who claimed to have seen the golden plates (though most allegedly visionary rather than physical form), linguistic features such as chiasmus and Hebraisms that allegedly demonstrate ancient Near Eastern literary patterns, and claimed archaeological correspondences. The Book of Mormon’s doctrinal content—presenting Jesus Christ as Savior, teaching principles of faith and repentance, and prophesying the restoration of Israel—provides what Latter-day Saints consider internal evidence of divine origin.

Doctrine and Covenants 20:9 declares the Book of Mormon contains “the fulness of the everlasting gospel,” making it not merely supplementary to the Bible but essential for salvation. The introduction to the Book of Mormon directs readers to pray about its truthfulness, promising they will receive confirmation from the Holy Ghost (citing Moroni 10:3-5), a promise known as “Moroni’s Promise.” However, this methodology embodies a classic circular reasoning fallacy: the Book of Mormon itself provides the test for verifying the Book of Mormon’s truthfulness. The text essentially instructs readers to assume its divine origin (that God will answer prayers about it), use that assumption as the basis for seeking confirmation, and then interpret any positive feeling as validation of the initial assumption. No external, objective verification is permitted to override this subjective spiritual experience. As Elder B.H. Roberts articulated: “The power of the Holy Ghost… must ever be the chief source of evidence for the Book of Mormon. All other evidence is secondary.” This prioritization of internal spiritual witness over external empirical verification—where the text being evaluated dictates the method of its own evaluation—represents a fundamentally different epistemology than historic Christianity’s commitment to publicly verifiable, historically testable truth claims.

The First Vision as Foundational Theophany

The First Vision narrative, as officially taught by the LDS Church, describes a pivotal event in spring 1820 when fourteen-year-old Joseph Smith Jr., confused by competing religious claims during a revival in Palmyra, New York, retired to a grove of trees to pray. There, according to the canonical 1838 account (Joseph Smith—History 1:15-20), he experienced a personal theophany in which God the Father and Jesus Christ appeared to him as two distinct personages. The Father introduced the Son, who informed Smith that all existing churches had fallen into apostasy and that he should join none of them. Christ also declared Smith’s sins forgiven. Critically, this account describes Smith seeing God the Father face to face—a claim that directly contradicts explicit biblical teaching. Exodus 33:20 records God’s declaration to Moses: “You cannot see my face, for man shall not see me and live.” The biblical commentary on this passage emphasizes: “It clearly stands forth in this passage that all other appearances of God to his servants, no matter how vivid or how they were stated to have occurred, did NOT include seeing God’s face. The Lord proclaimed here that such was impossible for any man to do and live. No exception to this truth would ever be made, not even for Moses!” This absolute prohibition—stated as a universal principle applying even to the greatest Old Testament prophet—makes Joseph Smith’s claim to have conversed face-to-face with God the Father theologically problematic from a biblical perspective. While theophanies of Christ (the pre-incarnate Logos) appear throughout Scripture, the Father remains invisible and unapproachable in his essence (1 Timothy 6:161 who alone has immortality, who dwells in unapproachable light, whom no one has ever seen or can see. To him be honor and eternal dominion. Amen.; John 1:182No one has ever seen God; God the only Son, who is at the Father’s side, he has made him known.; Colossians 1:153He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation.).

This event serves multiple theological functions in LDS thought. First, it establishes Joseph Smith as a prophet called directly by God, providing him with unique authority to restore true Christianity. Second, it demonstrates the corporeal, anthropomorphic nature of God—Father and Son appearing as distinct embodied beings, supporting distinctive LDS theological anthropology that rejects traditional Trinitarian formulations. Third, it initiates the restoration narrative by officially declaring the apostasy of all existing Christian churches. Fourth, it provides a personal pattern for receiving divine revelation through prayer, encouraging Latter-day Saints to seek individual spiritual confirmation. However, the First Vision account exists in multiple versions produced at different times in Smith’s life. The earliest account (1832) was written in Smith’s own hand but remained unpublished until rediscovered in the 1960s. This version describes seeing “the Lord” (singular) who forgave Smith’s sins, with no mention of the Father or the question about which church to join. An 1835 account mentions “many angels” and two personages, but differs in emphasis and details. The canonical 1838 account, not published until 1842, presents the most detailed version with Father and Son as distinct beings. A final 1842 account (the Wentworth Letter) provides a condensed version for public consumption.

LDS apologists argue these variations represent complementary perspectives emphasizing different aspects for different audiences, comparable to variations in the Gospel accounts of Jesus’ resurrection. Critics note more substantive discrepancies: the 1832 account’s singular divine personage versus the 1838 account’s Father and Son; the absence of any mention of the vision in contemporary documents or by Smith himself for over a decade; and the lack of external corroboration despite Smith’s claim of immediately sharing the experience and facing persecution. The official LDS Gospel Topics Essay on “First Vision Accounts” acknowledges these differences while maintaining their basic consistency, stating: “The various accounts of the First Vision tell a consistent story, though naturally they differ in emphasis and detail.”

The Role of Historical Claims in LDS Faith and Practice

These two historical claims—the Book of Mormon as ancient scripture and the First Vision as divine theophany—are inseparable from LDS identity and soteriology. Latter-day Saints regularly testify to their truth in testimony meetings, missionary work centers on sharing these claims, and temple recommend interviews assess belief in Joseph Smith’s prophetic calling (necessarily rooted in these founding events). The LDS understanding of salvation requires accepting the Book of Mormon as scripture and Joseph Smith as God’s prophet, making these historical claims soteriologically necessary rather than merely historically interesting.

This creates a unique epistemological framework: spiritual witness (the “burning in the bosom” from Moroni’s promise) takes precedence over historical or archaeological evidence. When DNA studies, linguistic analysis, or historical investigations challenge Book of Mormon historicity, Latter-day Saints are counseled to rely on spiritual confirmation rather than secular scholarship. Similarly, textual criticism of First Vision accounts is considered less probative than personal revelation. This prioritization of subjective spiritual experience over public, testable history represents a fundamental divergence from historic Christian epistemology, as we shall examine in the following sections.

Traditional Christian Understanding of Historical Foundations

Biblical Teaching on Scripture Formation and Authority

Historic Christianity grounds its scriptural authority in the concept of divine inspiration operating through identifiable human authors within specific historical contexts. The apostle Paul declares, “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness.” (2 Timothy 3:16). Peter explains this process: “No prophecy was ever produced by the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit.” (2 Peter 1:21). This understanding emphasizes both divine initiative (God’s breath, the Spirit’s carrying) and human instrumentality (men speaking and writing).

Crucially, biblical authority rests on eyewitness testimony and historical verification. Luke opens his Gospel by explaining his methodology: “Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word have delivered them to us, it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught” (Luke 1:1-4). Luke emphasizes multiple witnesses, careful research, orderly presentation, and the goal of historical certainty.

The apostle Peter similarly grounds Christian teaching in witnessed events rather than subjective experiences: “For we did not follow cleverly devised myths when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of his majesty.” (2 Peter 1:16). Peter explicitly contrasts eyewitness testimony with “myths,” emphasizing the public, verifiable nature of apostolic claims. This commitment to historical verification extends throughout the New Testament. Paul lists Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances to over 500 witnesses, many still living when he wrote, effectively inviting fact-checking (1 Corinthians 15:3-843 For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, 4 that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, 5 and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. 6 Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. 7 Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. 8 Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me.).

This biblical model of Scripture establishes several key principles: (1) Scripture arises from historical events witnessed by multiple parties, (2) scriptural claims can be investigated and verified through ordinary historical means, (3) the formation of Scripture occurred within identifiable historical contexts, and (4) the process of inscripturation was completed within the apostolic generation. The early Church recognized these principles in determining the New Testament canon, accepting only works with apostolic authorship or authorization, rejecting later pseudepigraphal writings regardless of their spiritual content.

The Sufficiency and Closure of the Biblical Canon

Historic Christianity affirms the sufficiency of Scripture—that the 66-book Protestant canon (or the larger Catholic/Orthodox canons) contains all revelation necessary for salvation and Christian life. Jude exhorts believers to “contend for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints.” (Jude 3), suggesting a completed deposit of apostolic teaching. Similarly, Hebrews opens by declaring that God “spoke to our fathers by the prophets” in “many times and in many ways” but “in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son.” (Hebrews 1:1-2). The implication is clear: God’s revelation reached its climax and completion in Jesus Christ and the apostolic witness to him. The Reformation principle of sola scriptura—Scripture alone as the final authority in matters of faith and practice—does not deny the Spirit’s ongoing work of illumination but rejects claims of new authoritative revelation equal or superior to Scripture. As the Westminster Confession states: “The whole counsel of God concerning all things necessary for His own glory, man”s salvation, faith and life, is either expressly set down in Scripture, or by good and necessary consequence may be deduced from Scripture: unto which nothing at any time is to be added, whether by new revelations of the Spirit, or traditions of men.”

This understanding excludes the possibility of additional ancient scriptural records like the Book of Mormon appearing in the nineteenth century. If the biblical canon is sufficient and complete, containing “the whole counsel of God” necessary for salvation, then no additional scripture—whether ancient or modern—is theologically necessary or possible without contradicting Scripture’s own self-testimony. The claim that Nephite prophets in ancient America produced scripture unknown to the biblical writers and Church Fathers fundamentally challenges this traditional understanding of canon closure.

The Resurrection as Historical Bedrock

If any historical claim defines Christianity, it is the bodily resurrection of Jesus Christ. Paul declares this the cornerstone of faith: “If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain… If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins.” (1 Corinthians 15:14, 17). The resurrection is not a subjective spiritual experience but a physical, historical event—Jesus’ tomb was empty, his body was raised, he appeared to disciples who touched him and ate with him.

The historical attestation for Jesus’ resurrection far exceeds that available for any other ancient event. Multiple independent sources (four Gospels, Paul’s epistles, other New Testament writings) record it. The earliest creedal formula, embedded in 1 Corinthians 15:3-853 For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, 4 that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, 5 and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. 6 Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. 7 Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. 8 Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me. and dating to within 3-5 years of the crucifixion, lists specific witnesses. The transformation of the apostles from fearful fugitives to bold proclaimers willing to die for their message demands a historical explanation. The empty tomb narrative, with women as primary witnesses (whose testimony was discounted in first-century Judaism), suggests authentic historical memory rather than fabrication.

Furthermore, the resurrection was proclaimed in Jerusalem immediately after it occurred, where opponents could have produced Jesus’ body to refute the claim. The early opponents of Christianity never denied the empty tomb but offered alternative explanations (the disciples stole the body, Matthew 28:11-15611 While they were going, behold, some of the guard went into the city and told the chief priests all that had taken place. 12 And when they had assembled with the elders and taken counsel, they gave a sufficient sum of money to the soldiers 13 and said, “Tell people, ‘His disciples came by night and stole him away while we were asleep.’ 14 And if this comes to the governor’s ears, we will satisfy him and keep you out of trouble.” 15 So they took the money and did as they were directed. And this story has been spread among the Jews to this day.. The rapid growth of the Church despite fierce persecution is historically inexplicable apart from the disciples’ genuine conviction that they had encountered the risen Christ. This model of public, verifiable, multiply-attested historical events stands in sharp contrast to Joseph Smith’s private visions. The First Vision—occurring in an isolated grove, known only through Smith’s later conflicting accounts, lacking any contemporary documentation or eyewitnesses, and not publicly claimed until over a decade after its supposed occurrence—cannot be subjected to the same historical scrutiny as Jesus’ resurrection. While this does not prove the First Vision false, it places it in a fundamentally different category epistemologically: it requires trust in Smith’s personal testimony rather than the kind of public verification Christianity demands for its central claims.

Comparative Analysis

Authority of Scripture vs. Continuing Revelation

At the heart of the divide between traditional Christianity and Latter-day Saint thought lies fundamentally different epistemologies—different ways of knowing what is true and how we can be certain of it. Historic Christianity grounds religious authority in the completed biblical canon, understood through the illumination of the Holy Spirit working in the believing community across two millennia. The LDS tradition embraces an open canon, with ongoing revelation through living prophets who can produce new scripture and correct previous understanding.

This difference is not merely theoretical but has profound practical implications. For traditional Christians, theological disputes are adjudicated by careful exegesis of Scripture, informed by creedal tradition and the historic interpretive community. Doctrines must be demonstrated from Scripture through sound hermeneutical principles. The “rule of faith” (regula fidei) established by the early Church Fathers provided boundaries for interpreting Scripture, ensuring that novel interpretations did not contradict the apostolic deposit.

In contrast, LDS epistemology permits—indeed requires—acceptance of Joseph Smith’s unprecedented claims to ancient American scripture and modern divine theophanies. When nineteenth-century Americans had no evidence for Hebrew civilizations in the Americas, when DNA studies demonstrated Native Americans’ Asian rather than Middle Eastern origins, when archaeological excavation failed to uncover Nephite artifacts, and when linguistic analysis found no trace of Hebrew or Egyptian influence on pre-Columbian American languages, the LDS response has been to prioritize spiritual witness over empirical investigation.

This represents more than different weighting of evidence types—it reflects incommensurable views of how religious truth is established. Christianity’s historic commitment to reason alongside revelation, expressed in Anselm’s “faith seeking understanding“ and developed through scholasticism and the Reformation, holds that true faith never contradicts reason or empirical evidence rightly understood. As Francis Schaeffer argued, Christianity offers “true truth”—claims about reality that can be investigated, tested, and verified. The LDS model, prioritizing subjective spiritual confirmation over objective historical investigation, operates on fundamentally different assumptions.

Historicity of the Book of Mormon: Evidence and Problems

The Book of Mormon makes numerous falsifiable historical claims that can be tested against archaeological, linguistic, and genetic evidence. These include the migration of Israelite groups to the Americas around 600 BC, the establishment of advanced civilizations with knowledge of metallurgy (steel swords, metal coins), domesticated animals (horses, cattle, sheep), and agricultural products (wheat, barley), written language derived from Hebrew and Egyptian, and large-scale warfare resulting in hundreds of thousands of casualties at specific locations. After nearly two centuries of investigation, none of these claims has found credible archaeological or scientific support.

DNA Studies: Perhaps the most devastating evidence against Book of Mormon historicity comes from genetic research. The book explicitly describes Lehi’s group as the “principal ancestors” (language conveniently changed to “among the ancestors” in 2006) of American Indians. However, comprehensive genetic studies consistently demonstrate that Native American populations derive from East Asian ancestry, with migration occurring 15,000-25,000 years ago via the Bering land bridge. No genetic markers supporting Middle Eastern origins have been found in pre-Columbian American populations.

The LDS Church’s own Gospel Topics Essay “Book of Mormon and DNA Studies” acknowledges: “The evidence assembled to date suggests that the majority of Native Americans carry largely Asian DNA.” It attempts to salvage Book of Mormon historicity through the “founder effect” argument—suggesting Nephite/Lamanite DNA might have been lost through genetic drift or swamped by larger populations. However, this requires accepting that a civilization described as numbering in the millions, engaged in massive construction projects and continent-spanning warfare, left no genetic trace whatsoever in descendant populations. Such special pleading strains credulity.

Archaeological Absence: Despite extensive excavation throughout the Americas, no archaeological evidence supports Book of Mormon claims. The Smithsonian Institution and National Geographic Society have both issued statements confirming that professional archaeologists find no scientific evidence for Book of Mormon peoples, places, or events. No Hebrew inscriptions, no reformed Egyptian writing, no Nephite coins, no steel swords, and no evidence of horses, cattle, wheat, or barley in pre-Columbian America have been discovered. LDS apologists have proposed the “Limited Geography Theory,” suggesting Book of Mormon events occurred in a small Mesoamerican region rather than spanning both American continents. While this accommodates some evidence problems, it contradicts the text’s descriptions of distances traveled, creates timeline impossibilities, and requires reading Cumorah (where the final Nephite-Lamanite battle occurred and Mormon buried the plates) as two different locations—one in Mesoamerica and one in New York. The theory essentially saves the Book of Mormon only by radically reinterpreting what it actually says.

Anachronisms: The Book of Mormon describes technologies, animals, plants, and cultural elements that did not exist in the Americas during the time period claimed. These include: horses (extinct in the Americas 10,000 years before Lehi’s journey), cattle, sheep, goats, wheat, barley, steel, iron, swords, chariots, silk, elephants (extinct), coins, and synagogues. The presence of extensive quotations from the King James Version of the Bible—including passages from Malachi (written after 600 BC) and textual variants unique to the KJV (produced in 1611)—demonstrates that the text could not have been written before 1611.

Linguistic Evidence: Professional linguists find no evidence of Hebrew or Egyptian influence on pre-Columbian American languages. The claimed “reformed Egyptian” has no linguistic referent—no such language is known to have existed. The “characters” Martin Harris showed to Charles Anthon in 1828 (the famous Anthon incident) were later identified by Anthon himself as a mix of “Greek and Hebrew letters, crosses and flourishes… arranged in columns.” When asked if the characters were authentic, reformed Egyptian, Anthon reportedly laughed and declared them an obvious fraud.

Nineteenth-Century Theology: Close reading reveals the Book of Mormon addresses debates specific to Joseph Smith’s time and place: anti-Masonic sentiment in the “secret combinations” theme, the great revival controversy in First Nephi’s church disputes, proto-Campbellite restorationism in numerous passages, and anti-Catholic sentiment throughout. The theology often reflects Protestant concerns of the 1820s rather than ancient Jewish or Christian thought. As historian Dan Vogel demonstrates, even the book’s anti-Masonic content parallels contemporary New York newspapers’ treatment of the William Morgan affair.

The cumulative weight of this evidence led even faithful LDS historian B.H. Roberts to privately acknowledge serious problems with Book of Mormon historicity. In his confidential 1922 study for Church leadership, Roberts wrote: “Did Ethan Smith’s View of the Hebrews furnish structural material for Joseph Smith’s Book of Mormon? It has been pointed out in these pages that there are many things in the former book that might well have suggested many major things in the other.” While Roberts never publicly rejected the Book of Mormon, his honest scholarship forced him to recognize the text’s nineteenth-century origins.

Reliability of the First Vision Accounts

The First Vision presents different but equally serious historical problems. Unlike the Book of Mormon’s falsifiable archaeological claims, the First Vision is a private revelatory experience that cannot be directly verified or falsified. However, the existence of multiple contradictory accounts, the late emergence of the narrative, and the absence of contemporary corroboration raise fundamental questions about its historicity.

The 1832 Account: Written in Joseph Smith’s own hand approximately 12 years after the alleged vision, this is the earliest documented version. Significantly, it describes seeing “the Lord”—singular—who forgave Smith’s sins. There is no mention of God the Father, no question about which church to join, no declaration that all churches are wrong, and no mention of persecution following the vision. The theological concerns are personal (Smith’s sins) rather than institutional (which church is true).

The 1835 Account: Recounted to Robert Matthews, this version mentions “many angels” (adding some credibility to our “tongue-in-cheek” photo above) and later two personages, one of whom identified himself as the Son. The emphasis shifts to discovering which church is correct, though the narrative remains substantially different from later versions.

The 1838 Account: Not published until 1842, this version became canonical in the Pearl of Great Price. It presents the now-familiar story: Father and Son as two distinct embodied beings, the Father introducing the Son, a clear declaration that all churches are corrupt, and emphasis on Smith’s prophetic calling. This account serves clear theological purposes in supporting distinctive LDS doctrines about God’s nature and the Great Apostasy. These are not minor variations in emphasis but substantive differences in core elements. The evolution from one divine personage to two, from personal sin concerns to institutional questions, and from no mention of religious persecution to claims of immediate and severe opposition suggests narrative development rather than multiple retellings of a single experience.

The Late Emergence Problem: Perhaps most troubling is the complete absence of any mention of the First Vision in contemporary documents, published materials, or even in Joseph Smith’s own writings for over a decade after it supposedly occurred. The vision that supposedly inaugurated God’s restoration was not mentioned in: The Book of Mormon (1830), The earliest revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants, the Church’s official history published in 1834 by Oliver Cowdery with Smith’s assistance (which begins with an angel appearing in 1823), contemporary newspapers, or any personal journals or letters.

LDS historian James B. Allen admits: “There is little if any evidence, however, that by the early 1830″s Joseph Smith was telling the story in public.” The silence is particularly striking given Smith’s claim in the 1838 account that he immediately shared the vision and suffered persecution for it. If the First Vision occurred in 1820 as claimed, why was it unknown to Church members, ignored in missionary work, and absent from foundational documents for the critical first decade of Mormonism?

Comparison with New Testament Accounts: LDS apologists frequently compare First Vision variations to differences in Gospel accounts of Jesus’ resurrection or Paul’s Damascus road experience. However, this comparison fails under scrutiny. The Gospels were written by different authors at different times for different audiences, with variations arising from multiple witnesses to public events. Paul’s conversion involved public elements (his companions heard the voice, he appeared before witnesses immediately after), was documented in multiple independent sources (Acts, Paul’s letters), and occurred shortly before the earliest documentation. The conversion transformed Paul from persecutor to proclaimer in a publicly verifiable way.

In contrast, the First Vision accounts come from a single source (Joseph Smith) with no corroborating witnesses, describing a completely private experience, documented only years or decades after the fact, with substantive rather than incidental variations, and serving clear theological purposes that evolved with Smith’s developing doctrine. The comparison to Gospel variations does not strengthen the First Vision’s credibility but highlights its evidential weaknesses.

Epistemological and Soteriological Implications

These historical problems create a fundamental epistemological crisis for anyone seriously investigating LDS claims. Traditional Christianity invites historical investigation of its foundational claims. Paul explicitly grounds Christian faith in the verifiable resurrection: “If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile.” (1 Corinthians 15:17). Christianity stakes everything on the historical reality of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection—events that occurred in public, were witnessed by many, and can be investigated through normal historical methods.

The LDS response to historical challenges has been to retreat from historical claims to spiritual witness. Moroni’s Promise (Moroni 10:3-5) directs seekers to pray and receive personal confirmation through the Holy Ghost rather than evaluate historical evidence. Elder Dallin H. Oaks stated explicitly: “It is our position that secular evidence can neither prove nor disprove the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.” This privileging of subjective spiritual experience over objective historical investigation represents a fundamentally different epistemology than historic Christianity.

The soteriological implications are equally significant. LDS theology makes salvation contingent upon accepting Joseph Smith as a prophet and the Book of Mormon as scripture. The third Article of Faith declares: “We believe… that Christ will reign personally upon the earth; and that the earth will be renewed and receive its paradisiacal glory.” This millennial reign is tied directly to the LDS restoration narrative—Christ will return to a church restored through Joseph Smith. Without the historical reality of the First Vision and the Book of Mormon, this entire soteriological structure collapses.

Traditional Christianity, in contrast, grounds salvation in Christ’s historical work: “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” (Romans 10:9). Salvation depends on the historical reality of Jesus’ resurrection, not on accepting nineteenth-century prophetic claims. Christians can investigate the historical evidence for Jesus’ resurrection and ground their faith in publicly verifiable events rather than private visions or subjective spiritual feelings.

This difference extends to ecclesiology. The LDS Church claims unique authority through priesthood restoration, making membership in the LDS Church necessary for salvation and temple ordinances essential for exaltation. Historic Christianity recognizes the Church universal—all who confess Jesus as Lord and trust in his finished work. Denominational differences exist, but salvation does not depend on membership in any particular organization or acceptance of any prophet’s private revelations.

Conclusion: Divergent Foundations

This examination of LDS historical claims regarding the Book of Mormon and First Vision reveals fundamental incompatibility with historic Christian orthodoxy. The differences are not peripheral but concern the very nature of revelation, the grounds of faith, the formation of Scripture, and the basis of salvation. The Book of Mormon’s claims to ancient American authorship have not withstood scholarly scrutiny. DNA evidence, archaeological investigation, linguistic analysis, and textual examination consistently point to nineteenth-century American origins rather than ancient Hebrew composition. The text’s anachronisms, King James Bible quotations (including translation errors unique to the KJV), nineteenth-century theological concerns, and lack of any physical or cultural trace in pre-Columbian America provide overwhelming evidence of modern production.

The First Vision accounts present equally serious difficulties. Multiple contradictory versions, late emergence of the narrative, absence of contemporary documentation, lack of corroborating witnesses, and the vision’s clear theological utility in supporting evolving LDS doctrines all raise questions about its historicity. Unlike Jesus’ resurrection—proclaimed immediately, witnessed by many, transforming public behavior, and documented while witnesses lived—the First Vision remained unknown and unproclaimed for over a decade, was witnessed by no one, and exists only in Smith’s own conflicting accounts.

These historical problems reflect bigger theological differences. The LDS commitment to ongoing revelation through living prophets, acceptance of additional scripture, anthropomorphic understanding of God, and priesthood-centered soteriology all depend on accepting Joseph Smith’s unique prophetic authority. That authority, in turn, rests entirely on the historical reality of the First Vision and the Book of Mormon. When historical investigation fails to support these foundational claims, the entire restoration narrative is called into question.

Historic Christianity grounds faith differently. The biblical canon is closed, having been completed by the apostolic generation who witnessed Jesus’ ministry, death, and resurrection. As Hebrews declares, God’s final and complete revelation has come through his Son (Hebrews 1:1-271 Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, 2 but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world.). The faith “once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3) requires no supplementation by ancient American scripture or modern prophetic revelation. Christian faith rests on publicly attested historical events—supremely Jesus’ resurrection—that can be investigated through normal historical methods rather than on private visions or subjective spiritual experiences.

The LDS response to these historical challenges—prioritizing spiritual witness over historical investigation—represents a fundamentally different epistemology than Christianity’s. While the Holy Spirit’s illumination is essential for understanding Scripture, Christianity has never retreated to purely subjective experience when faced with historical questions. The early Church Fathers defended Christianity’s historical claims against pagan critics by appealing to eyewitness testimony, contemporary documentation, and publicly verifiable events. They invited investigation rather than counseling believers to rely solely on private spiritual confirmation.

This analysis should not be mistaken for personal animosity toward Latter-day Saints. Many LDS believers demonstrate admirable devotion, moral seriousness, and genuine spiritual seeking. The LDS community’s emphasis on family, service, and moral living reflects values Christians share. However, theological clarity requires honest acknowledgment that Mormonism and historic Christianity rest on incompatible foundations.

Christians engaged in dialogue with Latter-day Saints must understand that differences extend beyond distinctive doctrines to the very basis of religious knowledge and authority. When an LDS missionary invites someone to “pray about the Book of Mormon,” they are not simply asking for openness to additional scripture but calling for acceptance of a completely different epistemological framework—one that privileges subjective spiritual experience over historical investigation and public verification.

The path forward requires both clarity and charity. Christians should clearly articulate why they cannot accept LDS historical claims while treating Latter-day Saints with respect and genuine concern for their spiritual well-being. The gospel invitation remains what it has always been: trust in Jesus Christ’s finished work, affirmed by his historical resurrection, documented by eyewitness testimony, and proclaimed by the Church across two millennia. This invitation requires no acceptance of golden plates in New York or private visions in sacred groves but simply faith in the publicly attested Christ of Scripture.

As Peter proclaimed at Pentecost: “Let all the house of Israel therefore know for certain that God has made him both Lord and Christ, this Jesus whom you crucified.” (Acts 2:36). The certainty Peter offered was grounded in witnessed events: Jesus’ miracles performed before many, his crucifixion as a public execution, his resurrection testified to by hundreds. This remains Christianity’s offer—not private mystical experiences or unverifiable ancient records but the publicly attested truth of Jesus Christ, who died for sins, rose from the dead, and offers salvation to all who believe. The considerable issues with Joseph Smith’s history and the Church’s historical claims contribute to the difficulty of resolving these fundamental differences. Yet truth matters, and honest engagement requires acknowledging where evidence leads. For those seeking truth about LDS historical claims, the path is not to suppress questions or rely solely on subjective feelings but to examine the evidence carefully, weigh competing explanations honestly, and ground faith in what can be publicly verified and historically demonstrated. That path leads not to golden plates and modern prophets but to the ancient, attested, sufficient gospel of Jesus Christ.