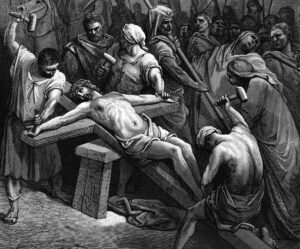

Photo: Jesus Christ being nailed to the Cross. Illustrator: Gustave Doré (circa 1885)

A Comprehensive Biblical and Historical Examination of the Iconography of the Cross.

The crucified Jesus stands as Christianity’s central symbol of redemption, forgiveness, and eternal life—a paradoxical image that has defined the faith for two thousand years. Yet the stark contrast between the brutality of Roman execution and the message of divine love it represents raises compelling questions for those unfamiliar with Christian theology. How did an instrument of torture and humiliation become the most recognizable symbol of hope in human history?

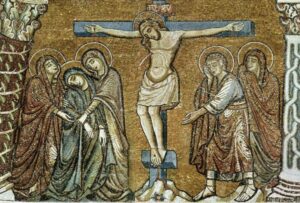

Since Christianity’s earliest days, the Church has grappled with this seeming contradiction. The adoption of the cross—the very tool of Jesus’ execution—as the faith’s primary emblem might appear counterintuitive, even disturbing, to the uninitiated. The evolution of crucifixion imagery itself tells a remarkable story: from early Christian hesitancy to depict the scene at all, to medieval portrayals emphasizing Christ’s suffering, to later representations emphasizing his triumph over death. This theological transformation reflects a deepening understanding of the cross’s multifaceted meaning. Despite depicting a man subjected to extreme cruelty and public shame, the image today evokes profound feelings of sacrificial love, divine justice satisfied, and the fulfilled promise of redemption in believers worldwide.

The crucifixion of Jesus Christ stands as the pivotal event in Christian theology, signifying the fulfillment of God’s covenant with humanity and the resolution of humanity’s fundamental problem: separation from God due to sin. In this act of supreme sacrifice, Jesus—understood in orthodox Christianity as both fully divine and fully human—took upon himself the sins of the world, absorbing God’s righteous judgment and offering humanity a path to redemption and reconciliation. His death on the cross is not merely a historical event confined to first-century Jerusalem but an eternal act of substitutionary atonement with ongoing salvific power, bridging the chasm between a holy God and fallen humanity.

The crucifixion of Jesus Christ stands as the pivotal event in Christian theology, signifying the fulfillment of God’s covenant with humanity and the resolution of humanity’s fundamental problem: separation from God due to sin. In this act of supreme sacrifice, Jesus—understood in orthodox Christianity as both fully divine and fully human—took upon himself the sins of the world, absorbing God’s righteous judgment and offering humanity a path to redemption and reconciliation. His death on the cross is not merely a historical event confined to first-century Jerusalem but an eternal act of substitutionary atonement with ongoing salvific power, bridging the chasm between a holy God and fallen humanity.

This sacrifice transcends time and space, offering salvation to all who place their faith in Christ’s finished work. The bodily resurrection of Jesus three days later further solidifies this doctrine, confirming his victory over sin, death, and Satan, and establishing a new covenant based not on human performance but on divine grace and forgiveness received through faith. The eternal significance lies in the promise of everlasting life for believers—a testament to God’s unwavering love and commitment to humanity’s salvation through the once-for-all sacrifice of his Son.

Yet among the various religious movements that have emerged in America, one stands conspicuously apart in its relationship to this universal Christian symbol: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While claiming the name of Jesus Christ prominently in their institutional title and insisting on their Christian identity, the LDS Church has systematically distanced itself from the cross—the very emblem that has represented Christ’s salvific work throughout Christian history. This symbolic reluctance raises profound theological questions about the nature of LDS soteriology, their understanding of Christ’s atonement, and the movement’s relationship to historic, biblical Christianity.

The Cross in Scripture: The Unshakeable Foundation

Before examining the LDS departure from cross-centered theology, we must establish the overwhelming scriptural emphasis on the cross as the locus of atonement. The New Testament writers, under divine inspiration, consistently and repeatedly point to the cross—not to any garden—as the place where redemption was accomplished.

The Apostle Paul, Christianity’s greatest theologian, declared unequivocally: “For the preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness; but unto us which are saved it is the power of God” (1 Corinthians 1:18, KJV). Notice Paul’s precise language: it is the preaching of the cross—not the preaching of a garden experience—that constitutes the power of God unto salvation. This is not incidental phraseology; it is the deliberate, Spirit-inspired declaration of where God’s saving power is located.

Paul elaborates further in his epistle to the Galatians: “But God forbid that I should glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, by whom the world is crucified unto me, and I unto the world” (Galatians 6:14, KJV). The apostle’s boasting, his glorying, his entire Christian identity centers not on gardens or temples, but exclusively on the cross. This singular focus demands our attention.

To the Corinthian church, Paul made his theological priorities crystal clear: “And I, brethren, when I came to you, did not come with excellence of speech or of wisdom declaring to you the testimony of God. For I determined not to know anything among you except Jesus Christ and Him crucified“ (1 Corinthians 2:1-2, NKJV). Paul determined—he made a deliberate, conscious choice—to know nothing except Christ crucified. Not Christ in Gethsemane, not Christ ascending to celestial kingdoms, but Christ crucified.

The Apostle Peter, writing to dispersed believers, declares: “He himself bore our sins in his body on the cross, so that we might die to sins and live for righteousness; by his wounds you have been healed” (1 Peter 2:24, NIV). The location is explicit: on the cross. The mechanism is clear: in his body. The result is definitive: you have been healed. Peter leaves no ambiguity about where the sin-bearing occurred.

The writer of Hebrews echoes this emphasis: “Fixing our eyes on Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of faith. For the joy set before him he endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God” (Hebrews 12:2, NIV). Jesus endured the cross—this was the focal point of His suffering, the apex of His sacrifice.

Paul’s letter to the Colossians provides perhaps the most comprehensive statement: “And through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross“ (Colossians 1:20, NIV). Reconciliation, peace, universal restoration—all accomplished through his blood, shed on the cross. The cross is where the blood was shed that makes peace with God possible.

Additionally, Colossians 2:14 declares: “Having canceled the charge of our legal indebtedness, which stood against us and condemned us; he has taken it away, nailing it to the cross“ (NIV). Our debt of sin was nailed to the cross—not left in a garden, but affixed permanently to the instrument of Christ’s death. The legal transaction of our redemption occurred at Golgotha.

Ephesians 2:16 continues this theme: “And in one body to reconcile both of them to God through the cross, by which he put to death their hostility” (NIV). The reconciliation of Jews and Gentiles to God occurred through the cross. The hostility between sinful humanity and a holy God was put to death at Calvary, not at Gethsemane.

“It Is Finished”: The Definitive Declaration

On the cross, Jesus uttered the powerful words “It is finished” (John 19:30)—words that ring throughout history as the sign that man’s sin is forever defeated and the power of death broken. The significance of this statement is often diminished when translated from the Greek into English. When Jesus cries out “it is finished” on the cross, the Greek word used is tetelestai (τετέλεσται), which means to bring to a close, to complete, to fulfill.

What makes this exclamation truly unique is the Greek tense that Jesus used. The perfect tense in Greek is rare in the New Testament and has no direct English equivalent. The perfect tense combines two Greek tenses: the Present tense (linear, ongoing) and the Aorist tense (punctiliar, a specific point in time). The combination of these two tenses in the perfect tense, as used in John 19:30, is of overwhelming significance to the Christian. When Jesus says “It is finished” (or completed), what he is actually saying is “It is finished and will continue to be finished.”

In Jesus’ statement “It is finished,” we have a declaration of salvation that is both momentary and eternal, Aorist and Present, linear and punctiliar. We are saved at a specific point in time—“it is finished”—our debt is paid, we are ransomed from the kingdom of darkness, and then we confidently rest in the reality that “it will continue to be finished” because we are in a position of grace and stand justified for all time before God. One Greek word, tetelestai, spoken in the perfect tense by Jesus on the cross, means “it was finished at that moment, and for all time.

Columbia International University: It Is Finished. (A Look at the Greek)

On the cross Jesus utters the powerful words “It is finished”; words that ring throughout history as the sign that man’s sin is forever defeated and the power of death broken. However, much of the significance of this statement is actually lost when the Greek is translated into English. When Jesus cries out “it is finished” on the cross, the Greek word used is “tetelestai” which means to bring to a close, to complete, to fulfill.

The combination of these two tenses in the perfect tense as used in John 19:30 is of overwhelming significance to the Christian. When Jesus says “It is finished” (or completed) what he is actually saying is “It is finished and will continue to be finished.”

What makes this exclamation truly unique however, is the Greek tense that Jesus used. (Verb tenses are the most important and most communicative part of the Greek language. This also is sometimes necessarily lost in translation.) Jesus speaks in the perfect tense, which is very rare in the New Testament and has no English equivalent. The perfect tense is a combination of two Greek tenses: the Present tense, and the Aorist tense. The Aorist tense is punctiliar: meaning something that happens at a specific point in time; a moment. The Present tense is linear: meaning something that continues on into the future and has ongoing results/implications.

In Jesus’ statement “It is finished” we have a declaration of salvation that is both momentary and eternal, Aorist and Present, linear and punctiliar. We are saved at a specific point in time, “it is finished”, our debt is paid, we are ransomed from the kingdom of darkness, and then we confidently rest in the reality that “it will continue to be finished” because we are in a position of grace and stand justified for all time before God. One Greek word, tetelestai, spoken in the perfect tense, by Jesus on the cross, and it was finished at that moment, and for all time. (1 John 19:30)

This declaration was not made in Gethsemane. It was not spoken in some garden of anguish. It was proclaimed from the cross, in the final moments before Christ gave up His spirit. The atonement was completed at Calvary. Our own efforts, no matter how devout or charitable, can never surpass the sufficiency of Jesus’s sacrifice on the cross to make us worthy of Heaven.

The Cross as the Universal Christian Symbol

In the first chapter of his influential work The Cross of Christ, British Anglican priest and theologian John Stott traces the historical development of the cross as a symbol within Christianity. He observes that the shadow of the cross fell upon Jesus from his very birth—his death was central to his mission from the beginning.

“A universally acceptable Christian emblem would obviously need to speak of Jesus Christ, but there was a wide range of possibilities. Christians might have chosen the crib or manger in which the baby Jesus was laid, or the carpenter’s bench at which he worked as a young man in Nazareth, dignifying manual labour, or the boat from which he taught the crowds in Galilee, or the apron he wore when washing the apostles’ feet, which would have spoken of his spirit of humble service. Then there was the stone which, having been rolled from the mouth of Joseph’s tomb, would have proclaimed his resurrection. Other possibilities were the throne, symbol of divine sovereignty, or the dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit sent from heaven on the Day of Pentecost. Any of these seven symbols would have been suitable as a pointer to some aspect of the ministry of the Lord. But instead the chosen symbol came to be a simple cross.”

— John Stott, The Cross of Christ

Stott’s observation is profoundly significant. The early church, guided by apostolic teaching and the Holy Spirit, deliberately chose the cross—not the empty tomb, not the ascending Lord, not any other symbol—as the central representation of their faith. This choice reflects the theological conviction that the cross is where salvation was accomplished.

“Every time we look at the cross Christ seems to say to us, ‘I am here because of you. It is your sin I am bearing, your curse I am suffering, your debt I am paying, your death I am dying.’ Nothing in history or in the universe cuts us down to size like the cross.”

“It was by his death that he wished above all else to be remembered. There is then, it is safe to say, no Christianity without the cross. If the cross is not central to our religion, ours is not the religion of Jesus.”

The LDS Church’s Systematic Rejection of the Cross

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints occupies a unique position in its self-identification as a Christian church with its institutional rejection of the cross as a symbol. Unlike other denominations that have embraced this ancient Christian emblem, the LDS Church has systematically distanced itself from the cross for nearly a century, developing what scholars have termed a “cross taboo” within Mormon culture.

Historically, this was not always the case. In nineteenth-century Mormonism, crosses were common in church art, on stained-glass windows, on pulpits, on gravestones, and in quilts. Brigham Young’s wives and daughters wore cross jewelry. Crosses even appeared as the official LDS Church cattle brand in the Salt Lake Valley. Two temples—the Hawaiian Temple and the Cardston, Alberta Temple—were described in a 1923 General Conference as being built in the shape of a cross. In 1916, the LDS Church itself petitioned the Salt Lake City Council to erect a massive cross on Ensign Peak as “the symbol of Christianity” to honor Mormon pioneers.

So what changed? How did Latter-day Saints come to be so firmly opposed to the cross as a symbol?

According to historian Michael G. Reed, author of Banishing the Cross: The Emergence of a Mormon Taboo, the shift began in the mid-twentieth century and was deeply rooted in anti-Catholic sentiment. LDS leaders experienced growing tension with the Catholic Church, with some privately linking Catholicism to the “great and abominable church of all the earth” referenced in 1 Nephi 14. While never publicly expressed, this disdain eventually led to the rejection of the cross as an acceptable personal symbol for Latter-day Saint members.

The firm institutionalization of this rejection took hold during the presidency of David O. McKay, the ninth president of the LDS Church. President McKay served as president of the European mission in the 1920s and recorded in his journal negative impressions of Catholic practices he observed. When Catholic-LDS relations became strained in Utah during the 1950s, the cross became a casualty of this institutional conflict.

In 1957, when a jewelry store in Salt Lake City advertised cross necklaces for girls, LDS Presiding Bishop Joseph L. Wirthlin contacted President David O. McKay to ask whether it was appropriate for Latter-day Saint girls to purchase and wear them. President McKay’s response effectively codified the Mormon cross taboo: “This is purely Catholic and Latter-day Saint girls should not purchase and wear them… Our worship should be in our hearts.”

This private sentiment soon became public doctrine. In 1958, Elder Bruce R. McConkie wrote negatively about wearing crosses in his influential (though unofficial) book Mormon Doctrine, describing such practice as “inharmonious” with Latter-day Saint worship. McConkie went so far as to compare the cross to the “mark of the beast,” and his father-in-law, LDS President Joseph Fielding Smith, compared the cross to a guillotine—merely “tools of execution.”

These statements reveal a fundamental misunderstanding of the cross’s theological significance in Christian tradition. While McKay’s characterization of the cross as “purely Catholic” ignores its universal adoption across all branches of Christianity—Protestant, Orthodox, and Catholic alike—from the earliest centuries, his reduction of worship to internal sentiment alone dismisses two millennia of Christian practice that views visible symbols as aids to devotion rather than replacements for it. The comparison of the cross to execution tools like guillotines, while technically accurate regarding its original function, misses the transformative theological point entirely: Christians don’t venerate the cross because it was an execution device, but because of who died upon it and what his death accomplished. The guillotine executed countless criminals; the cross bore the sinless Son of God who died as a substitutionary sacrifice for humanity’s sins. This is not a distinction without difference—it is the difference between a mere historical artifact and a symbol of divine redemption that has shaped Western civilization for two thousand years.

Moreover, the argument that two millennia of historical distance from the crucifixion event somehow provides license to compare it to modern execution methods reflects a profound misunderstanding of how symbols acquire and retain meaning across time. Cultural significance is not eroded by chronological distance; rather, it is often deepened and enriched through centuries of theological reflection, artistic expression, and lived experience within communities of faith. To suggest that the cross is functionally equivalent to a guillotine or electric chair simply because all are instruments of death is to ignore how meaning is embedded, transmitted, and preserved through cultural and religious tradition. The cross did not become Christianity’s central symbol by accident or through mere passage of time—it was deliberately embraced by the earliest Christians precisely because it represented the climactic moment of God’s redemptive work in human history. No modern method of execution carries such theological weight or historical continuity, and analogies between them are therefore fundamentally flawed.

President Gordon B. Hinckley’s Formalization

The institutional position was further solidified by President Gordon B. Hinckley. In a 1975 General Conference address, Hinckley recounted an exchange with a Protestant minister who toured a newly renovated LDS temple:

“I’ve been all through this building, this temple which carries on its face the name of Jesus Christ, but nowhere have I seen any representation of the cross, the symbol of Christianity. I have noted your buildings elsewhere and likewise find an absence of the cross. Why is this when you say you believe in Jesus Christ?”

President Hinckley’s response has become the standard LDS explanation:

“I do not wish to give offense to any of my Christian brethren who use the cross on the steeples of their cathedrals and at the altars of their chapels, who wear it on their vestments, and imprint it on their books and other literature. But for us, the cross is the symbol of the dying Christ, while our message is a declaration of the living Christ.”

— President Gordon B. Hinckley, “The Symbol of Christ,” General Conference, 1975

President Hinckley continued:

“The lives of our people must become the only meaningful expression of our faith and, in fact, therefore, the symbol of our worship… Because our Savior lives, we do not use the symbol of His death as the symbol of our faith. But what shall we use? No sign, no work of art, no representation of form is adequate to express the glory and the wonder of the Living Christ.”

This reasoning, while rhetorically appealing, contains a fundamental flaw: Protestant Christians who wear crosses also worship a living Christ. The cross reminded Christians that Jesus died for their sins, but it has always been empty because He is risen and is no longer there. As one Presbyterian believer pointedly responded to a Latter-day Saint who made this argument: “The cross reminded us that Jesus died for our sins, but it is empty because He is risen.” The cross, properly understood, proclaims both death AND resurrection, sacrifice AND triumph.

The Irony of the New Church Symbol

In April 2020, President Russell M. Nelson announced a new symbol for the LDS Church—a visual representation featuring the Christus statue beneath an arch, with the church’s name in a cornerstone. President Nelson declared, “The symbol will now be used as a visual identifier for official literature, news, and events of the Church. It will remind all that this is the Savior’s Church and that all we do as members of His Church centers on Jesus Christ and His gospel.”

In April 2020, President Russell M. Nelson announced a new symbol for the LDS Church—a visual representation featuring the Christus statue beneath an arch, with the church’s name in a cornerstone. President Nelson declared, “The symbol will now be used as a visual identifier for official literature, news, and events of the Church. It will remind all that this is the Savior’s Church and that all we do as members of His Church centers on Jesus Christ and His gospel.”

The irony is profound on multiple levels. President Gordon B. Hinckley had previously declared: “No sign, no work of art, no representation of form is adequate to express the glory and the wonder of the Living Christ.” Yet the LDS Church now employs precisely that—a sign, a work of art, a representation of form—as its official symbol. The contradiction becomes even more striking when one considers that while the Church rejects the cross (which Christians have used for two millennia as their identifying symbol), it has instead adopted a nineteenth-century Danish Lutheran statue created by Bertel Thorvaldsen for Copenhagen’s Church of Our Lady. Meanwhile, the golden figure of the angel Moroni—a distinctively Mormon icon with no parallel in biblical Christianity—graces the pinnacle of virtually every LDS temple worldwide, serving as the faith’s most recognizable architectural signature.

This selective iconography reveals the inconsistency in Mormon reasoning about religious symbolism. The phrase “graven image” appears in Exodus 20:4 as part of the second commandment, translating a Hebrew word that means literally “an idol.” While Christians understand that venerating the cross as a symbol of Christ’s redemptive work differs fundamentally from idolatry, the LDS Church’s simultaneous adoption of a sculpted statue as its official identifier while positioning golden statuary atop its most sacred buildings raises pointed questions about consistency in its iconographic theology. If the objection to the cross is rooted in concerns about graven images or inadequate representations of Christ, how do these concerns not apply equally—or more so—to the Church’s own chosen visual symbols?

An interesting observation about Mormon symbols…

Anybody who has visited Salt Lake City will quickly notice that Mormon symbols are found throughout the downtown area. Probably its best known symbol is the angel Moroni. Ironically, this trumpet-blowing effigy stands in the same place a Christian cross would probably stand if LDS temples were Christian churches.

The Salt Lake Temple showcases an elaborate array of symbolic imagery that stands in stark contrast to the LDS Church’s rejection of the cross. Beehives symbolizing industry, moonstones representing different stages of existence, sunstones depicting celestial glory, the all-seeing eye of divine providence, and various Masonic handclasp symbols known as “grips” adorn the temple’s exterior in abundance. Most notably, numerous five-pointed pentagrams—inverted stars traditionally associated with occult symbolism—decorate both the Salt Lake City and Nauvoo temples prominently.

While Mormon apologists are quick to distance themselves from Christianity’s ancient cross, arguing against physical representations of Christ’s sacrifice, they vigorously defend these esoteric symbols as legitimate expressions of faith. The pentagrams alone, which appear dozens of times on temple architecture, represent a far more controversial symbolic choice than the cross ever could. This selective embrace of elaborate iconography while simultaneously rejecting Christianity’s most universal symbol exposes a fundamental inconsistency: the issue was never truly about avoiding religious symbolism, but rather about distancing Mormonism from historic Christian orthodoxy and its central message of substitutionary atonement accomplished at Calvary.

The Garden Atonement: A Theological Departure

The LDS reluctance to embrace the cross is intimately connected to a distinctive doctrinal development: the emphasis on Gethsemane rather than Calvary as the primary location of the atonement. This theological shift represents a significant departure from biblical Christianity and helps explain why the cross holds diminished significance in Mormon thought.

A Brigham Young University study asked students where “the Atonement of Christ mostly took place.” The results were striking: 88 percent answered “In the Garden of Gethsemane.” Only 12 percent chose “On the Cross at Calvary.” This reveals a fundamental soteriological difference between LDS theology and historic Christianity.

The Encyclopedia of Mormonism, drawing on multiple twentieth-century LDS church leaders, explicitly states: “For Latter-day Saints, Gethsemane was the scene of Jesus’s greatest agony, even surpassing that which he suffered on the cross.” According to this heterodox view, Jesus “suffered the pains of all men… principally in Gethsemane,” thereby relocating the center of Christian soteriology from Calvary to the Garden.

This teaching finds no support in Scripture. The Garden of Gethsemane is mentioned in only two Gospel accounts (Matthew 26:36-46; Mark 14:32-42), and neither passage attributes atoning significance to Jesus’ suffering there. While Mormon commentators frequently appeal to Luke’s description of Jesus sweating “great drops of blood” (Luke 22:44), the New Testament nowhere suggests this phenomenon bore redemptive significance. The sweating of blood—medically known as hematidrosis—was a physiological manifestation of extreme psychological and spiritual distress, not a mechanism of redemption or substitutionary atonement.

Orthodox Christian theology has always understood Gethsemane as revealing the genuine humanity of Christ in his incarnation. There, Jesus experienced profound human anguish as he contemplated the cup of divine wrath he would bear on behalf of sinners. His prayer—“Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me. Nevertheless, not my will, but yours, be done” (Luke 22:42)—demonstrates his full human nature shrinking from suffering while his divine will remained perfectly aligned with the Father’s redemptive plan. This is the mystery of the hypostatic union: Jesus, fully God and fully man, experienced authentic human emotion and temptation without sin.

The atonement itself, however, occurred on the cross. Scripture is unambiguous: “He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree” (1 Peter 2:24). It was there that Christ’s blood was shed, there that he cried “It is finished” (John 19:30), and there that redemption was accomplished once for all.

LDS Leaders on Gethsemane

Ezra Taft Benson, the thirteenth president of the LDS Church, taught:

“It was in Gethsemane that Jesus took on Himself the sins of the world, in Gethsemane that His pain was equivalent to the cumulative burden of all men, in Gethsemane that He descended below all things so that all could repent and come to Him.” (Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson, p. 15)

Marion Romney, a member of the LDS First Presidency, stated in a 1953 conference speech:

“Jesus then went into the Garden of Gethsemane. There he suffered most. He suffered greatly on the cross, of course, but other men had died by crucifixion; in fact, a man hung on either side of him as he died on the cross.”

Joseph Fielding Smith, the tenth LDS President, stated:

“We speak of the passion of Jesus Christ. A great many people have an idea that when he was on the cross, and nails were driven into his hands and feet, that was his great suffering. His great suffering was before he ever was placed upon the cross. It was in the Garden of Gethsemane that the blood oozed from the pores of his body.”

Bruce R. McConkie wrote:

“And as he came out of the Garden, delivering himself voluntarily into the hands of wicked men, the victory had been won. There remained yet the shame and the pain of his arrest, his trials, and his cross. But all these were overshadowed by the agonies and sufferings in Gethsemane.”

The Biblical Response: Death Is Required for Atonement

The biblical response to this teaching is unambiguous: death is required for atonement, not suffering alone. Whatever suffering Jesus endured in the Garden of Gethsemane, it did not and could not atone for our sin. That happened entirely on the cross. This is not merely a matter of emphasis; it is a fundamental principle of biblical soteriology.

God placed Adam and Eve in a perfect paradise with no death—until they partook of the forbidden fruit. God had told them: “If you eat of the fruit, you are sure to die” (Genesis 2:16-17). As a result of their sin, death entered the world. The Apostle Paul affirms: “The wages of sin is death” (Romans 6:23). Sin and death are inseparably connected from the very beginning of Scripture to its end.

The Old Testament sacrificial system demonstrates this connection repeatedly. Every year on the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), the ancient Hebrews killed an animal to atone for the sins of the nation. Leviticus 17:11 explains: “For the life of a creature is in the blood, and I have given it to you to make atonement for yourselves on the altar; it is the blood that makes atonement for one’s life.” The shedding of blood—which requires death—is the mechanism of atonement.

Hebrews 9:22 makes this principle explicit: “In fact, the law requires that nearly everything be cleansed with blood, and without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness.” No shedding of blood means no forgiveness. No death means no atonement. Jesus’ suffering in Gethsemane, however intense, could not accomplish atonement because He did not die there.

Romans 5:6-8 declares: “When we were utterly helpless, Christ came at just the right time and died for us sinners. Now, most people would not be willing to die for an upright person, though someone might perhaps be willing to die for a person who is especially good. But God showed his great love for us by sending Christ to die for us while we were still sinners.” It is Jesus’ death for us that mattered, not merely His suffering.

Furthermore, Romans 3:25 states that God “displayed publicly” Christ as a propitiation. When Jesus sweated drops of blood in the Garden of Gethsemane, that was not a public display. The sacrifice of redemption, where Jesus bore our sins as the propitiation, occurred in the public display of the cross.

Modern Christian Theologians on the Centrality of the Cross

Throughout Christian history and into the modern era, faithful theologians have consistently emphasized the centrality of the cross. Their witness stands in sharp contrast to the LDS de-emphasis of Calvary.

R.C. Sproul (1939-2017)

“The most obscene symbol in human history is the Cross; yet in its ugliness it remains the most eloquent testimony to human dignity.”

“On the cross, not only was the Father’s justice satisfied by the atoning work of the Son, but in bearing our sins the Lamb of God removed our sins from us as far as the east is from the west. He did it by being cursed. ‘Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us—for it is written, Cursed is everyone who is hanged on a tree’ (Galatians 3:13). He who is the incarnation of the glory of God became the very incarnation of the divine curse.”

“The idea of being the Substitute in offering an atonement to satisfy the demands of God’s law for others was something Christ understood as His mission from the moment He entered this world and took upon Himself a human nature. He came from heaven as the gift of the Father for the express purpose of working out redemption as our Substitute, doing for us what we could not possibly do for ourselves.”

D.A. Carson

“Do you wish to see God’s love? Look at the cross. Do you wish to see God’s wrath? Look at the cross.”

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892)

“Leave out the cross, and you have killed off the Gospel of Jesus. Atonement by the blood of Jesus is not an arm of Christian truth; it is the heart of it.”

“Jesus has borne the death penalty on our behalf. Behold the wonder! There He hangs upon the cross! This is the greatest sight you will ever see. Son of God and Son of Man, there He hangs, bearing pains unutterable, the just for the unjust, to bring us to God. Oh, the glory of that sight!”

Martin Luther (1483-1546)

The great Reformer’s famous theologia crucis (theology of the cross) forms the heart of Protestant theology:

“The cross alone is our theology.”

John Calvin (1509-1564)

“In the cross of Christ, as in a splendid theater, the incomparable goodness of God is set before the whole world. The glory of God shines… never more brightly than in the cross.”

Billy Graham (1918-2018)

“The heart of the Christian Gospel with its incarnation and atonement is in the cross and the resurrection. Jesus was born to die.”

“God undertook the most dramatic rescue operation in cosmic history. He determined to save the human race from self-destruction, and He sent His Son Jesus Christ to salvage and redeem them. The work of man’s redemption was accomplished at the cross.”

Elisabeth Elliot (1926-2015)

“To be a follower of the Crucified means, sooner or later, a personal encounter with the cross. And the cross always entails loss. The great symbol of Christianity means sacrifice, and no one who calls himself a Christian can evade this stark fact.”

A.W. Tozer (1897-1963)

“The cross that saves them also slays them, and anything short of this is a pseudo-faith and not true faith at all.”

P.T. Forsyth (1848-1921)

“A true grasp of the Atonement meets the age in its need of a centre, of an authority, of a creative force, a guiding line and a final goal. It meets our lack of a fixed point.”

— The Cruciality of the Cross

Historical and Archaeological Confirmation

The historical reality of crucifixion has been confirmed by both ancient sources and modern archaeology. When it comes to Jesus of Nazareth, one of the few things that scholars across the theological spectrum agree on is that He was crucified in first-century Jerusalem. The Romans executed most criminals by tying them to wooden crosses, so, unusually, Jesus was nailed—a fact that some have questioned. But archaeological discoveries continue to vindicate the biblical account.

In a recently published study in the Journal of Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, a team of scientists revealed that they had excavated a 2,000-year-old corpse from an isolated tomb near Venice in Northern Italy that showed signs of having been crucified. The heel of the skeleton has a hole through it consistent with the kind of injury that would have been sustained during crucifixion. This discovery, along with the famous Yehohanan heel bone discovered in Jerusalem in 1968, provides tangible archaeological evidence that confirms the biblical descriptions of crucifixion.

Crucifixion was the method the Romans used for executing slaves and those guilty of sedition. As the Roman politician Cicero noted, it was “the most cruel and hideous of tortures.” The Romans used this particularly brutal form of execution as a means of producing social conformity and terror among subject populations. That Jesus of Nazareth, claiming to be the Son of God and King of the Jews, would be executed by this method was both historically expected and theologically significant.

Addressing the “Pagan Origin” Objection

Some groups, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, have argued that the cross is derived from pagan symbols and therefore should not be used by Christians. This argument requires examination, as some Latter-day Saints have echoed similar reasoning.

The Institute for Religious Research summarizes the historical evidence:

“(1) The Romans did indeed crucify people in the time of Jesus using crossbeams. (2) Both Christians and non-Christians from at least the early second century agreed that Jesus had been crucified in that manner. (3) Christians did not borrow the idea of a cross from paganism. Rather, it was a form of execution used by the pagan Romans. Christians would certainly not have invented the idea that Jesus was crucified. (4) Although the cross became a prominent, public symbol of Christianity after Constantine, its use as a Christian symbol goes back to within a century or so of the time of Christ.”

The argument that the Christian cross is derived from pagan symbols due to the existence of similar shapes in ancient paganism is a logical fallacy. Here’s why:

Function over Form: The primary function of the cross in Christianity is as a symbol of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, a specific method of Roman execution. While similar shapes might exist in other cultures, their meaning and context are vastly different. The Christian cross is not defined by its shape alone, but by the event it represents.

Historical Context: The Romans used crucifixion as a common method of execution, and the cross shape naturally resulted from this practice. This historical context is crucial in understanding the origin of the Christian cross, and it predates the widespread use of similar symbols in various pagan religions.

Symbolic Evolution: Even if a cross-like symbol existed in paganism before Christianity, it doesn’t invalidate the Christian cross’s symbolism. Symbols can evolve and take on new meanings over time. The Christian cross transformed the symbol of a brutal execution into a representation of sacrifice, redemption, and hope.

Universality of Basic Shapes: The cross is a simple geometric shape, and it’s not surprising that similar shapes appear in various cultures throughout history. This doesn’t imply a direct connection or shared meaning between these symbols. To claim that the Christian cross is inherently pagan based on shape alone is an oversimplification that ignores historical and cultural context.

The existence of cross-like symbols in ancient paganism does not negate the historical and theological significance of the Christian cross. The Christian cross is firmly rooted in the historical reality of Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, and its meaning transcends any superficial similarities to other symbols.

The Cross as Reversal of the Fall

The theological significance of the cross extends beyond mere substitutionary atonement; it represents the comprehensive reversal of humanity’s exile from God that began in Eden. Rabbi Jason Sobel has observed the profound connections between Christ’s crucifixion and the undoing of the Fall:

“Every detail in Jesus’ crucifixion connects to undoing the Fall. His hands were pierced because our hands stole from the tree. His feet were pierced to fulfill the promise of Genesis 3:15 that the heel of the messianic Seed would crush the serpent’s head. His pierced side made atonement for Eve’s sin, the one taken from man’s side, who led Adam into temptation.”

Jesus’ experience on the cross reversed the four aspects of exile caused by the Fall:

First, Jesus reversed the spiritual aspect of exile by allowing Himself to be nailed to a tree—the very means of our spiritual exile from the garden. As it is written in Galatians 3:13, “Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us, for it is written: ‘Cursed is everyone who is hung on a tree.'” The cross was not merely an instrument of execution; it was the divinely appointed means by which the curse of Eden would be reversed.

Second, Jesus reversed the emotional aspect of exile by allowing Himself to experience the psychological and emotional pain of being mocked by men and feeling abandoned by God. His cry from the cross—“My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34)—represents the experience of divine abandonment that sin deserves. He bore our emotional separation from God so that we might never experience it eternally.

Third, Jesus reversed the relational aspect of exile by experiencing rejection and betrayal, and even while being mocked on the cross, He chose to extend forgiveness (Luke 23:34). The relational breach between humanity and God, between person and person, found its healing at Calvary. “For He Himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility” (Ephesians 2:14).

Fourth, Jesus reversed the physical aspect of exile by physically suffering on the cross. The crown of thorns, the physical sign of the curse of creation (Genesis 3:18), conveyed that the second Adam, the new representative head of creation, was reversing the exile and restoring the blessing by allowing the curse of creation to fall on His head. His nail-pierced hands redeemed the hands that took the forbidden fruit. His wounded side echoed the side from which Eve was taken.

This comprehensive reversal could only occur through the cross, not through suffering in a garden. The cross was God’s instrument of cosmic restoration. It is the axis upon which all of redemptive history turns—looking backward to Eden’s fall and forward to the New Jerusalem’s glory. No other location, no other event, carries this theological weight in Scripture.

The Necessity of Public Sacrifice

Scripture emphasizes that Christ’s atoning sacrifice was necessarily public. Romans 3:25 declares that God “presented Christ as a sacrifice of atonement, through the shedding of his blood—to be received by faith. He did this to demonstrate his righteousness.” The word “presented” or “displayed publicly” (Greek: proetheto) indicates that the atonement was meant to be witnessed, visible, and unmistakable.

This public display of propitiation stands in stark contrast to the private agonies of Gethsemane. While Jesus’ suffering in the garden was witnessed only by three sleepy disciples, the crucifixion was a public spectacle witnessed by crowds, soldiers, religious leaders, and passersby. The public nature of the cross fulfilled the typology of the Old Testament sacrificial system, where atonement was made openly at the altar, in the presence of the congregation.

Colossians 2:15 declares that Christ, on the cross, “disarmed the rulers and authorities and put them to open shame, by triumphing over them in him.” The cross was not merely a place of suffering but a place of public victory. Satan’s defeat was not accomplished in secret but displayed openly for all creation to witness. The public nature of the atonement was essential to its function as a divine declaration and cosmic triumph.

Unlikely Company: Other Groups That Reject the Cross

The LDS Church is not alone in its reluctance to embrace the cross, though its companions in this position may seem surprising. Jehovah’s Witnesses have argued that Jesus died on a stake rather than a cross and have rejected cross symbolism entirely, teaching that the cross is of pagan origin. The United Church of God similarly avoids the cross as a symbol of devotion.

The Institute for Religious Research, in response to Jehovah’s Witness arguments, observes: “Sadly, the Watchtower’s polemic against the cross obscures the very heart of the gospel.” The same might be said of any group that systematically distances itself from the cross of Christ.

A Call to Examination

For Latter-day Saints who take the Bible seriously, the questions raised by their church’s cross avoidance and Gethsemane emphasis deserve careful examination. Elder Gregory A. Schwitzer of the Seventy, writing in the official LDS Ensign magazine, acknowledged that the cross is important to LDS faith and that “the Redeemer’s suffering on the cross is vitally important to us and is an inseparable part of the Atonement.”

Yet Elder Schwitzer also quoted 1 Corinthians 1:18 selectively: “In his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul indicated that the ‘preaching of the cross… is the power of God.'” Let us restore the thirteen words Elder Schwitzer passed over:

“For the preaching of the cross is to them that perish foolishness; but unto us which are saved it is the power of God.”

— 1 Corinthians 1:18 (KJV)

Those who are being saved recognize the cross as the power of God. Those who are perishing consider it foolishness. Where does one’s theology fall on this spectrum? The answer has eternal significance.

While Elder Schwitzer correctly emphasizes the importance of the cross’s deeper meaning within the Atonement, his argument against the cross as a symbol overlooks its powerful unifying potential. The cross is not merely an outward sign; it’s a universally recognized symbol of Christianity, instantly communicating a shared faith and belonging. For anyone transitioning into faith, the cross can serve as a familiar bridge, easing their integration and fostering a sense of connection to their Christian heritage.

Furthermore, interpreting “taking up one’s cross” as purely metaphorical may be limiting. While personal sacrifice is undoubtedly crucial, the physical cross can serve as a tangible reminder of Christ’s ultimate sacrifice, inspiring devotion and strengthening faith. While the preaching of the cross is undeniably essential, dismissing the symbol altogether neglects its potential to unite, inspire, and invite. By embracing the cross alongside our understanding of its deeper significance, we can enrich our faith and create a more welcoming environment for all who seek to follow Christ.

The Methodist Warning: Keeping the Cross Central

In 1891, Christian Gore inaugurated what became a tradition among Anglican theologians when he placed the Incarnation at the center of Christian theology. The Methodists responded the following year with a strong and prophetic warning that remains relevant today:

“We rejoice in the prominence which is being given to the doctrine of the Incarnation, with all its solemn lessons and inspirations. But we must be careful lest the Cross passes into the background, from which it is the glory of our fathers to have drawn it. Give to the death of Christ its true place in your own experience and in your Christian work—as a witness to the real and profound evil of sin, as an overwhelming manifestation of Divine love, as the ground of acceptance with God, as a pattern of sacrifice to disturb us when life is too easy, to inspire and console us when life is hard, and as the only effectual appeal to the general heart of men, and, above all, as the Atonement for our sins.”

— Methodist response to the Bampton Lectures, 1892

This warning from over a century ago speaks directly to the LDS situation today. When any doctrine—whether incarnation, temple ordinances, garden suffering, or obedience to commandments—displaces the cross from its central position, the very heart of the gospel is compromised. The death of Christ is the ground of acceptance with God, the atonement for our sins. Nothing can substitute for it; nothing should overshadow it.

The Cross and Christian Discipleship

Jesus Himself commanded His followers to take up the cross. This was not merely metaphorical language; it was a call to identify with Him in His death and to follow Him even to the point of suffering:

“Then said Jesus unto his disciples, If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me. For whosoever will save his life shall lose it: and whosoever will lose his life for my sake shall find it. For what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul? or what shall a man give in exchange for his soul?”

— Matthew 16:24-26 (KJV)

To deny the cross as a symbol while claiming to follow Christ, who commanded us to “take up” the cross, represents a profound inconsistency. The cross is not merely an artifact of history; it is the pattern of Christian discipleship. Francis Schaeffer and others have captured this well:

“I am to face the cross of Christ in every part of life and with my whole man. The cross of Christ is to be a reality to me not only once for all at my conversion, but all through my life as a Christian. True spirituality does not stop at the negative (death), but without the negative—in comprehension and in practice—we are not ready to go on.”

— Francis Schaeffer“If we want proof of God’s love for us, then we must look first at the Cross where God offered up His Son as a sacrifice for our sins. Calvary is the one objective, absolute, irrefutable proof of God’s love for us.”

— Jerry Bridges“When you look at the Cross, what do you see? You see God’s awesome faithfulness. Nothing—not even the instinct to spare His own Son—will turn Him back from keeping His word.”

— Sinclair Ferguson

The Cross as the Fixed Point of History

The cross is not merely one event among many in Christian theology; it is the central pivot of God’s dealing with the universe in every aspect. Jessie Penn-Lewis writes:

“We need a ‘fixed point,’ which acts as a centre and a goal, and that ‘point’ in the history of the world—back to the ages before it, and forward to the ages following it—is the Cross of Calvary. It is the central pivot of the dealing of God with the universe in every aspect. It is because we Christians get away from the ‘fixed point’ of the Cross, that we wander into all kinds of cul-de-sac places, where we lose the balance and right perspective of truth.”

— Jessie Penn-Lewis, The Centrality of the Cross

She continues to explain the comprehensive nature of the cross’s significance:

“The cross is vital and central in connection with justification by faith; vital and central in connection with our victory over sin; vital and central in relation to our personal lives and our external habits; vital and central in connection with victory over our foe. Believers who know these aspects of the Cross find themselves standing on the solid foundation of the finished work of Christ, so that all hell cannot shake or overthrow them.”

— Jessie Penn-Lewis

The Cross and the Uniqueness of Christian Forgiveness

The cross stands as the unique foundation of forgiveness in Christianity, distinguishing the Christian faith from all other world religions. W.M. Clow makes this striking observation:

“There is no forgiveness in this world, or in that which is to come, except through the cross of Christ. ‘Through this man is preached unto you the forgiveness of sins.’ The religions of paganism scarcely knew the word… The great faiths of the Buddhist and the Mohammedan give no place either to the need or the grace of reconciliation. The clearest proof of this is the simplest. It lies in the hymns of Christian worship. A Buddhist temple never resounds with a cry of praise. Mohammedan worshippers never sing. Their prayers are, at the highest, prayers of submission and of request. They seldom reach the gladder note of thanksgiving. They are never jubilant with the songs of the forgiven.”

— W.M. Clow

This observation illuminates why the cross must remain central: it is the very foundation of Christian joy and worship. Remove the cross, diminish the cross, relocate the atonement to a garden—and you undermine the foundation of Christian confidence and praise. The songs of the forgiven flow from Calvary.

“All of heaven is interested in the cross of Christ, hell afraid of it, while men are the only ones to ignore its meaning.”

— Oswald Chambers

When I Survey the Wondrous Cross

In a profound irony, the Mormon Tabernacle Choir has performed Isaac Watts’ magnificent hymn “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross,” based on Galatians 6:14. The hymn expresses the very theology that the LDS institutional position on the cross seems to diminish:

When I survey the wondrous cross On which the Prince of glory died,

My richest gain I count but loss, And pour contempt on all my pride.

Forbid it, Lord, that I should boast, Save in the death of Christ my God!

All the vain things that charm me most, I sacrifice them to His blood.

Watts’ hymn captures the proper Christian response to the cross: not avoidance or embarrassment, but surveying, contemplating, glorying in, and boasting only in Christ’s death. This is the heritage of cross-centered Christianity that spans millennia and transcends denominational boundaries.

What Did Joseph Smith Actually Teach?

Interestingly, careful research reveals that the Gethsemane emphasis is a relatively late development in LDS theology, not something traceable to Joseph Smith himself. According to research published by BYU’s Religious Studies Center:

“With respect to the teachings and writings of Joseph Smith there is one reference to the Savior in Gethsemane (although not about his atoning for our sins) and thirty-four references to Christ’s Crucifixion, nine of which refer to its saving power. The purpose of this research is not to undermine the importance or significance of Christ’s experience in Gethsemane but rather to shed light on what Joseph Smith taught regarding Christ’s sufferings in Gethsemane and his death on Calvary. In contrast with the statement from the Encyclopedia of Mormonism cited in the introduction, the teachings and revelations of Joseph Smith give Christ’s death on the cross the primary locus of soteriological significance.”

— BYU Religious Studies Center

This finding is remarkable: even by LDS standards, the emphasis on Gethsemane over the cross appears to be a development that came after Joseph Smith, not something he established. The cross taboo and the garden atonement theology emerged together in the early-to-mid twentieth century, coinciding with growing anti-Catholic sentiment and the desire for Mormon distinctiveness. These were later theological innovations, not founding principles.

Latter-day Saints who value their founding prophet’s teachings should carefully consider whether the current institutional position on the cross actually reflects what Joseph Smith taught, or whether it represents a later departure that Smith himself did not embrace.

Conclusion: Embracing the Scandal

The cross of Jesus Christ, despite its origins in a horrific act of violence, has become the most powerful symbol of love, sacrifice, and redemption in human history. In embracing the paradox of the cross, Christians find the essence of their faith: a love so profound that it transcends the brutality of the crucifixion. The image of the cross serves as a poignant reminder of the sacrificial love that knows no bounds.

The Greeks and Romans reasoned that God’s Chosen One would never be treated as a rebellious slave on anything as utterly offensive and undignified as a cross. Yet in a strange twist of divine irony, the church now views this former symbol of humility and shame as the path to life and salvation. God designed His amazing plan of redemption so that the cross was the principal element in the drama that established the Christian faith.

As we gaze upon the cross, let us not shy away from its stark reality, but rather let it stir within us a profound awareness of forgiveness, sacrifice, salvation, and eternal life. The center of the gospel message is the cross. We should be reminded of the Apostle Paul’s convictional declaration “to preach Christ and Him crucified” in his first correspondence with the Corinthian church.

To the Latter-day Saint who sincerely seeks to follow Jesus Christ, I offer this challenge: Examine the Scriptures. Count how many times the cross and crucifixion are mentioned in connection with atonement, and how many times Gethsemane is given that role. Consider why the earliest Christians—including those who knew Jesus personally—chose the cross as their symbol. Ask why Paul, under divine inspiration, determined to know nothing except Christ crucified. Ponder why Jesus declared “It is finished” from the cross, not from the garden.

The cross calls us not to embarrassment but to embrace. It invites us not to symbolic avoidance but to theological adoration. It beckons us not to man-made alternatives but to the God-given instrument of our redemption.

“And I, brethren, when I came to you, did not come with excellence of speech or of wisdom declaring to you the testimony of God. For I determined not to know anything among you except Jesus Christ and Him crucified.”

— 1 Corinthians 2:1-2 (NKJV)

✝