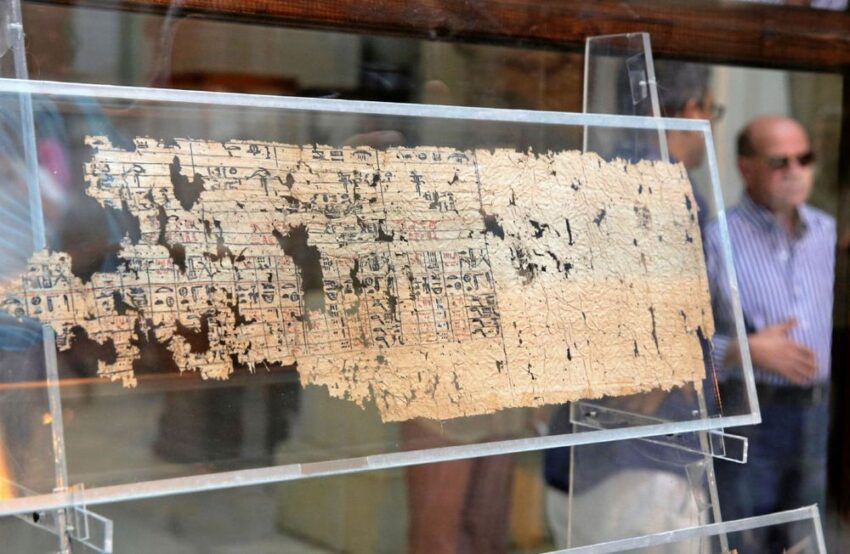

Photo: Papyrus containing the diary of Merer at the Wadi al-Jarf exhibition, Cairo Museum, 2016.

The Discovery, Translation, and Significance

of the World’s Oldest Written Papyri

A Find Without Precedent

In the annals of Egyptian archaeology, certain discoveries arrive with the force of revelation — moments when the ancient world suddenly speaks in a recognizable human voice. The unearthing of the Wadi al-Jarf Papyri in 2013 was exactly such a moment. Hidden for approximately 4,500 years in man-made limestone caves along Egypt’s Red Sea coast, these documents represent the oldest inscribed papyri ever recovered from ancient Egypt. Written in cursive hieroglyphs and early hieratic script, they contain something that no other text from the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt had ever provided: a firsthand, day-by-day account of the logistical machinery that built the Great Pyramid of Khufu.

To grasp the magnitude of this discovery, consider its chronological context. The famous Dead Sea Scrolls — long celebrated as among the oldest surviving manuscripts in the world — date to roughly the 3rd century BC through the 1st century AD. The Wadi al-Jarf Papyri predate even the earliest of those by more than two thousand years, placing them in the reign of Pharaoh Khufu, generally estimated at approximately 2589 to 2566 BC. They are, in the most literal and precise sense, documents from the dawn of recorded human history.

The Site: A Forgotten Harbor on the Red Sea

The story of this discovery begins not in 2013 but nearly two centuries earlier. In 1823, the English traveler and antiquarian John Gardner Wilkinson stumbled upon a peculiar set of ruins on the Egyptian shore of the Red Sea, approximately 119 kilometers south of the modern city of Suez. Wilkinson noted the site but misidentified it as a Greco-Roman necropolis, and the desert reclaimed it for another 185 years.

It was not until 2008 that serious archaeological attention returned to Wadi al-Jarf. French Egyptologist Pierre Tallet, then of the University of Paris-Sorbonne, began systematic survey work at the location, initially in collaboration with the French Institute of Archaeological Studies (IFAO) in Cairo. What Tallet and his colleagues began to uncover was not a burial ground but something far more astonishing: the oldest known harbor in human history, a sophisticated port infrastructure that dated without ambiguity to the Fourth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, some 4,500 years ago.

Wadi al-Jarf sits at a strategically logical point on the Red Sea coast, just 35 miles from the Sinai Peninsula — close enough on a clear day to see the mountains rising across the water. The Sinai held copper and turquoise mines of immense value to the Egyptian state. The harbor, Tallet and his team established through pottery analysis, cartouche inscriptions, and stratigraphic evidence, was inaugurated during the reign of Pharaoh Sneferu — Khufu’s father — and was active through Khufu’s own reign, at which point it was sealed and apparently never reopened.

The physical scale of Wadi al-Jarf was itself revelatory. A 600-foot stone jetty extended into the sea. Some 130 stone anchors were recovered from the site. Most dramatically, thirty large limestone storage galleries — galleries of a size that American Egyptologist Mark Lehner compared to “Amtrak train garages” — had been carved directly into the hillside to shelter wooden boats when the harbor was not in active use. It was at the entrance to these galleries that the most extraordinary find of Tallet’s career was waiting.

The Discovery of the Papyri

In the closing days of the 2013 excavation season, Tallet and co-director Gregory Marouard turned their attention to a narrow passageway between two massive limestone blocks that had been used to seal one of the storage galleries. The blocks themselves were inscribed — as was almost every substantial surface at Wadi al-Jarf — with the cartouches and team designations of Khufu’s workforce. But what lay between them was something no one had anticipated.

Wedged in the gap, some buried in a pit and some apparently displaced, were hundreds of papyrus fragments. Several of the scrolls were still partially rolled and, in at least some cases, still tied with rope, as if they had been hastily gathered and sealed into the gallery closure at the moment the harbor was decommissioned. The dry desert air and the sealed limestone environment had preserved them with a quality of survival that, by any measure, was miraculous. Among these fragments were approximately ten papyri in particularly good condition, as well as numerous smaller pieces representing several dozen individual documents. The best-preserved scrolls measured nearly two feet in length.

The discovery was highly serendipitous. Such records would normally have been brought back to the Nile Valley to be archived, but for some reason, these documents were left at Wadi al-Jarf. Facts and Details Tallet’s own interpretation is elegantly simple and poignant: “I imagine because of the death of the king, they just stopped everything and closed up the galleries and then, as they were leaving, buried the archives in the area between the two large stones used to seal the complex.” Amusing Planet The date inscribed on the papyrus appears to be the 26th or 27th year of Khufu’s reign, which scholars broadly accept as the final year of his rule. These men were, in essence, finishing the Great Pyramid when their king died, and their world stopped.

The Researchers

Pierre Tallet is the central scholarly figure in this discovery. A professor of Egyptology at the University of Paris IV (Paris-Sorbonne), Tallet has spent much of his career studying the ancient Egyptian presence along the Red Sea coast. His systematic excavations at Wadi al-Jarf, conducted under the auspices of a joint expedition from Paris-Sorbonne, the IFAO, and Assiut University in Egypt, represent decades of methodical fieldwork in some of Egypt’s most inhospitable terrain.

Gregory Marouard, co-director of the excavation and an affiliated scholar with the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, played an equally essential role in the field work and the initial analysis of the finds. Together, Tallet and Marouard published the first formal scholarly account of the harbor and its papyri in 2014 in Near Eastern Archaeology (Volume 77:1), establishing the academic foundation for what has become one of the most discussed archaeological discoveries of the 21st century.

In 2017, Tallet published the formal critical edition of the most important documents, Les papyrus de la Mer Rouge I: Le “Journal de Merer” (Papyrus Jarf A et B), through the IFAO in Cairo — a trilingual volume in French, English, and Arabic containing the full text, translation, and analysis of what are now designated Papyrus Jarf A and Papyrus Jarf B.

Mark Lehner, director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates and arguably the foremost American Egyptologist working at Giza, was among the scholars who traveled to Wadi al-Jarf to assess the finds. His evaluation was unambiguous. “The power and purity of the site is so Khufu,” he said. “The scale and ambition and sophistication of it — the size of these galleries cut out of rock like the Amtrak train garages, these huge hammers made out of hard black diorite they found, the scale of the harbor, the clear and orderly writing of the hieroglyphs of the papyri, which are like Excel spreadsheets of the ancient world — all of it has the clarity, power and sophistication of the pyramids, all the characteristics of Khufu and the early fourth dynasty.” Facts and Details

The Man Called Merer

At the heart of the most significant papyri is a single individual: a man identified by the Egyptian title sehedj — meaning Inspector — whose name was Merer. He was not a pharaoh, not a high priest, not an architect of renown. He was, in the parlance of modern organizational hierarchy, a middle manager: a skilled overseer who commanded a team of approximately 200 men organized into four groups of 40 — what the Egyptians called a phyle. His team’s formal designation was “The Escort Team of ‘The Uraeus of Khufu Is Its Prow,'” a name that referenced the serpent prow of their vessel and signaled their direct service to the royal project.

What Merer left behind were not literary compositions or theological texts but something far more prosaic and, in historical terms, far more valuable: daily logbooks. The entries are all arranged along the same line. At the top, there is a heading naming the month and the season. Under that, there is a horizontal line listing the days of the month, and below each day heading are two columns of hieratic text detailing the team’s activities that day. History of Information Tallet has described the documents as resembling ancient spreadsheets — systematic, administrative, and relentlessly practical. They were written every single day, as analysis of the ink and composition confirms.

What Merer recorded, with the scrupulous attention of a man whose professional reputation depended on accurate accounting, was the transportation of white limestone casing blocks from the quarries at Tura — located on the east bank of the Nile near modern Cairo — to the construction site at Giza. The best-preserved sections document the transportation of white limestone blocks from the Tura quarries to Giza by boat. Wikipedia

What the Papyri Record

The documents that have been most thoroughly translated — Papyrus Jarf A and Papyrus Jarf B — cover several months of operations, generally understood to span from approximately July to November. They describe a logistical rhythm of remarkable efficiency.

Merer’s team made two to three round-trip journeys every ten days between the Tura quarries and the Giza plateau. Each loaded boat carried approximately 30 blocks weighing 2 to 3 tonnes each — a total cargo load of 70 to 80 tonnes per voyage. Over a single month, Merer’s team delivered approximately 200 blocks. During the peak Nile flood season, when high waters made the river and associated canals most navigable for heavily laden vessels, the team could potentially move up to 1,000 blocks in a single operational period. This was the white Tura limestone used for the pyramid’s exterior casing — the gleaming outer skin of the Great Pyramid that blazed in the Egyptian sun and has long since been stripped away, leaving the rougher granite core we see today.

The daily entries are specific. A representative sample from the translated text gives the texture of Merer’s world:

Day 25: Inspector Merer spends the day with his phyle hauling stones in Tura South; spends the night at Tura South. Day 26: Inspector Merer casts off with his phyle from Tura South, loaded with stone, for Akhet-Khufu; spends the night at She-Khufu. Day 27: Sets sail from She-Khufu, sails towards Akhet-Khufu, loaded with stone, spends the night at Akhet-Khufu.

“Akhet-Khufu” — the Horizon of Khufu — was the Egyptian name for the Great Pyramid itself. “She-Khufu” — the Lake of Khufu — refers to a harbor or artificial basin near the Giza plateau where the boats were unloaded. This detail alone has proven immensely valuable to scholars.

The Canal System and the Harbor at Giza

One of the most significant implications of Merer’s diary concerns the physical infrastructure of the Giza plateau during the pyramid’s construction. The Nile today runs several miles from Giza. How, then, did Merer’s boats deliver their enormous stone cargo to the pyramid site itself?

The papyri offer important support for a hypothesis that Lehner had been developing for several years — that the ancient Egyptians, masters of canal building, irrigation, and otherwise redirecting the Nile to suit their needs, built a major harbor or port near the pyramid complex at Giza. Smithsonian Magazine Merer’s references to the “Ro-She Khufu” — the Mouth of the Lake of Khufu — and to the “She Akhet Khufu” — the Lake of the Horizon of Khufu — provide textual confirmation that such a hydraulic infrastructure existed. According to Egyptologist Mark Lehner, this supports scholars’ theory that the ancient Egyptians built a network of artificial basins that allowed heavily laden boats to deposit their cargo at the plateau’s edge, facilitating the delivery of materials necessary to construct the pyramid. Archaeology Magazine

In short, the Egyptians did not haul the casing stones overland from the riverbank. They engineered a canal and harbor system that brought the Nile’s waters — and Merer’s loaded boats — directly to the pyramid construction zone. The diary is, among many other things, a witness to one of the most ambitious hydraulic engineering projects of the ancient world.

Ankhhaf and the Chain of Command

The papyri also illuminate the administrative hierarchy supervising the pyramid’s construction. Merer makes repeated reference to a superior identified as “the noble Ankhhaf,” described as overseer of the Ra-shi-Khufu — the harbor at Giza. Ankhhaf was the half-brother of Pharaoh Khufu, known from other sources, who is believed to have been a prince and vizier under Khufu and/or Khafre. Wikipedia. His appearance in Merer’s logbooks places him at the operational center of the pyramid’s final construction phases — a significant historical corroboration of a figure previously known only from funerary contexts.

The Workers: Skilled, Compensated, and Fed

The Wadi al-Jarf Papyri have added important nuance to long-standing debates about the nature of the pyramid workforce. For generations, popular imagination — and not a small amount of ideologically motivated theorizing — has imagined the pyramids as the product of enslaved labor. The picture Merer’s diary and the associated supply records paint is considerably more complex and, in human terms, more dignified.

Merer’s detailed payment records demonstrate that those who built the pyramids were skilled workers who received compensation for their services. National Geographic. The workers ate well: according to the papyri, the laborers were provisioned with meat, poultry, fish, and beer. Smithsonian Magazine Working on the royal boats, the papyri suggest, was a source of genuine social prestige. The inscriptions found throughout the Wadi al-Jarf site — on pottery, copper tools, boat fragments, and even pieces of textile — consistently link the workers to royal service in terms that emphasize honor and association with the king’s eternal project.

Other Papyri in the Archive

While Merer’s diary has attracted the most scholarly and popular attention, it represents only a portion of the Wadi al-Jarf archive. Papyrus C mentions the construction of nautical facilities, and Papyrus D details surveillance work performed around the Khufu funerary complex. National Geographic Additional fragments contain administrative accounts of commodities delivered to workers — detailed records of rations, supplies, and materials that collectively paint a portrait of an extraordinarily sophisticated state bureaucracy operating at full stretch to complete one of history’s most ambitious construction projects.

The full archive, once all fragments are conserved and analyzed, is expected to shed further light on the organization of labor across the entire pyramid-building enterprise, the supply chains connecting the Nile Valley to the Sinai mines, and the administrative language and practices of Egypt’s Fourth Dynasty.

The Significance: Silencing the Fringe

For serious historians and Egyptologists, the Wadi al-Jarf Papyri are not a surprise — they are a confirmation. The scholarly consensus that the Great Pyramid was built by organized teams of Egyptian workers under royal direction, using sophisticated logistics, engineering, and administrative systems, has never been seriously threatened within academic circles. What the discovery provides is something beyond theoretical consensus: it provides a name, a voice, and a daily record.

Merer was real. He lived in the 26th year of Khufu’s reign. He loaded limestone blocks at Tura South and sailed them down to a harbor at Giza. He reported to a half-brother of the pharaoh. He supervised forty boatmen. He wrote it down every day. The pyramid was built by Egyptians, organized by Egyptians, administered by Egyptians, in the service of an Egyptian king — and we have the paperwork.

The persistent fringe claims that the pyramids were built by a lost antediluvian civilization, by extraterrestrial engineers, or by any agency other than the people whose names and records are now in our possession, were always contradicted by the cumulative weight of Egyptian archaeology. The Wadi al-Jarf Papyri do not merely add to that weight — they add a firsthand human witness. As Tallet himself has noted, there is nothing in the ancient record quite like Merer’s diary: “This kind of narrative is very rare from that time. All the narrative texts we have from the Fourth Dynasty are basically biographical texts found in tombs.” Facts and Details

Current Status: Conservation and Publication

The papyri are currently held and displayed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, where they were exhibited beginning in 2016 in a dedicated installation. The bulk of the fragmentary material has been placed in 70 frames of conservation glass for preservation and ongoing study. The formal scholarly publication process is continuing, with Tallet’s 2017 volume addressing Papyri A and B being the first installment of what is expected to be a multi-volume critical edition covering the entire archive.

The site of Wadi al-Jarf itself continues to be excavated by Tallet’s team. Each season brings additional inscriptions, additional artifacts, and additional context for understanding what was, in the reign of Khufu, one of the most strategically important ports on the ancient Red Sea.

Conclusion: What the Papyri Tell Us — and What They Do Not

The Diary of Merer and the Wadi al-Jarf Papyri represent, without exaggeration, one of the most important documentary discoveries in the history of Egyptology. They are not merely old, though at 4,500 years they are older than any inscribed papyrus previously known. They are informative in ways that no tomb inscription, funerary text, or royal stele could ever be: they record the ordinary daily life of a working man in the employ of a king, during the months in which the greatest structure the ancient world would ever build was being given its final face of gleaming white stone.

Yet it is essential to understand precisely what window these documents open — and how narrow that window is.

Merer was not a pyramid builder in the sense that most people imagine. He was a logistics officer operating at a specific and relatively late stage of the construction project. His records document the delivery of white Tura limestone casing stones — the smooth exterior skin applied to the pyramid’s outer surface — during what scholars believe to be the final year or two of Khufu’s reign. By the time Merer was making his runs between Tura South and Giza, the pyramid’s core structure had almost certainly already been raised to its full height. He was, in modern construction terms, overseeing the finish work on a building whose frame was already standing.

This means the papyri are entirely silent on the questions that have most persistently animated — and divided — Egyptological scholarship. How were the millions of core limestone and granite blocks quarried, shaped, and moved across the plateau during the decades of primary construction? What ramp system, if any, was employed to raise those blocks as the pyramid grew higher? Was there a single external ramp, an internal spiraling ramp, multiple counter-ramps, or some combination of techniques that has left no surviving documentation? How were the colossal granite beams of the King’s Chamber — each weighing up to 70 tonnes — lifted and positioned with such precision? What was the organizational sequence by which hundreds of thousands of blocks were placed in their courses, and what surveying and leveling methods were used to maintain the pyramid’s extraordinary geometric accuracy across more than 13 acres of base?

On none of these questions does Merer offer a single syllable. His diary tells us about boats, rations, canals, harbor logistics, and administrative reporting chains. It is invaluable for understanding the supply infrastructure supporting the project’s late phase. It tells us the workers were skilled, compensated, and organized. It gives us one named official in one team performing one category of task. It does not describe the core construction methods that remain, to this day, the subject of active and unresolved debate among Egyptologists and engineers.

There is also much that even the broader archive leaves untouched. The papyri do not record the architectural decision-making process, the identity of the pyramid’s chief architect beyond what is already known from other sources, the religious or cosmological logic governing the monument’s orientation and internal chamber design, or the experience of the tens of thousands of workers who labored on the core structure during the pyramid’s main construction decades.

Merer did not set out to explain the Great Pyramid to future generations. He was doing his job, logging his movements, accounting for his men and his cargo. That those logs survived — sealed in limestone by men who likely never imagined they would see daylight again — is one of history’s most consequential accidents of preservation. They confirm, with the authority of a contemporary witness, that Egyptians built the pyramid, that the state organized that effort with formidable administrative sophistication, and that the logistics of its final phase involved hydraulic infrastructure and long-distance material transport of remarkable scale.

But the deeper mysteries of the Great Pyramid — how its builders solved, day by day and course by course, the staggering engineering problems of raising 2.3 million blocks to a height of 481 feet with tools of copper and stone — remain unresolved. Merer saw the pyramid from the water, approaching with a boatload of casing stones, watching its finished silhouette rise against the desert sky. He did not leave us a blueprint. The men who could have written that document never did, or if they did, the desert has not yet given it back.

Sources consulted include: Tallet, P. & Marouard, G., “The Harbour of Khufu on the Red Sea Coast at Wadi al-Jarf, Egypt,” Near Eastern Archaeology 77:1 (2014); Tallet, P., Les papyrus de la Mer Rouge I: Le “Journal de Merer” (Papyrus Jarf A et B), IFAO, Cairo, 2017; Stille, A., “The World’s Oldest Papyrus and What It Can Tell Us About the Great Pyramids,” Smithsonian Magazine, October 2015; Weiss, D., “Journeys of the Pyramid Builders,” Archaeology Magazine, July/August 2022; National Geographic, “This Ancient Diary Reveals How Egyptians Built the Great Pyramid,” 2024.