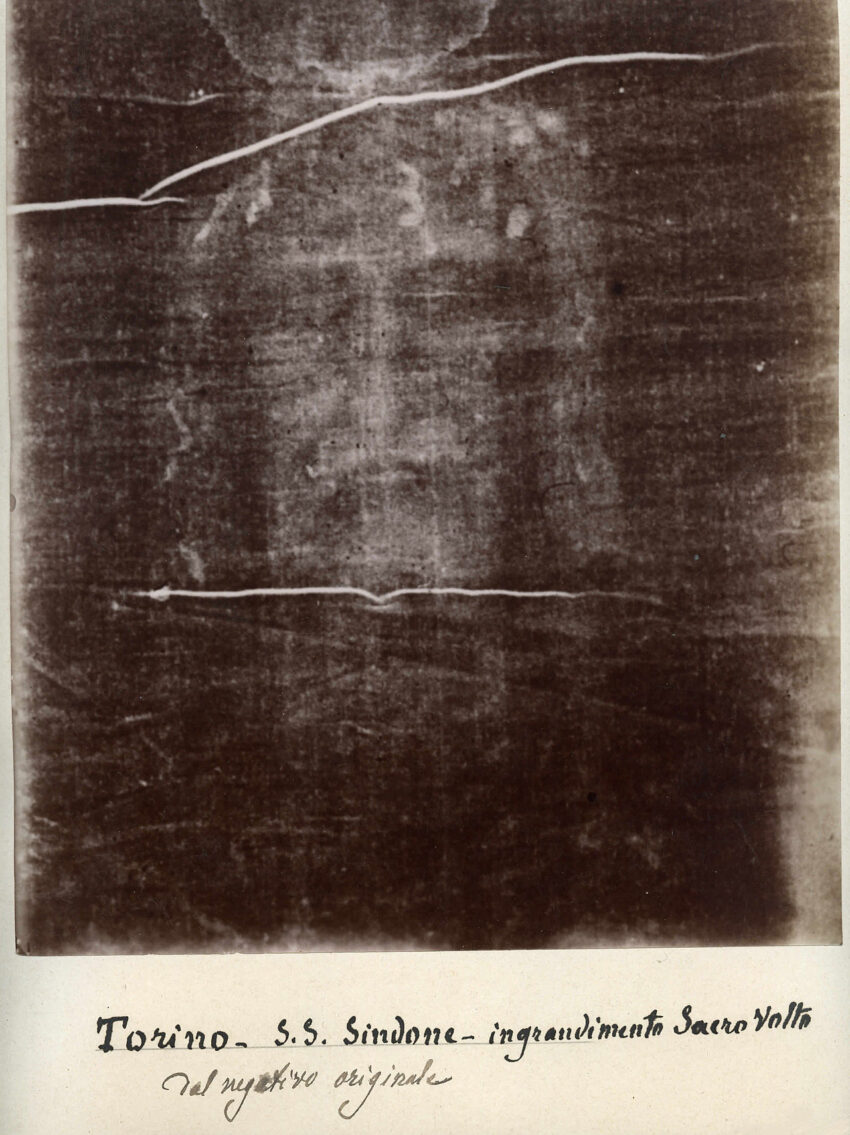

Photo: Secondo Pia’s 1898 negative of the image on the Shroud of Turin has an appearance suggesting a positive image. It is used as part of the devotion to the Holy Face of Jesus. Image from Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne. Via Wikimedia. U.S. work that is in the public domain.

Why the Shroud of Turin Cannot Be the Burial Cloth of Jesus Christ

A Biblical and Historical Examination

Introduction: The Seduction of Sacred Relics

Few objects in the history of Christendom have generated as much fascination, reverence, controversy, and theological confusion as the Shroud of Turin. Housed today in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy, this strip of linen — approximately fourteen feet long and three and a half feet wide — bears the faint, reddish-brown image of the front and back of a bearded man who appears to have suffered wounds consistent with crucifixion. For millions of Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox faithful, the cloth is nothing less than the authentic burial shroud of Jesus of Nazareth, an artifact so sacred that its periodic expositions draw pilgrims from around the globe.

The pull of the Shroud is understandable. Human beings are tactile, embodied creatures. We long to touch, see, and handle that which is holy. From the earliest centuries of the church, the veneration of relics — fragments of bone, pieces of wood alleged to be from the True Cross, articles of clothing supposedly worn by saints — has served a powerful psychological and spiritual function. Relics anchor transcendent realities to physical experience. They make the invisible visible. When the invisible in question is the resurrection of Jesus Christ, the desire to possess tangible confirmation of that event is intensely human.

No medieval institution illustrates this desire more vividly — or more controversially — than the Knights Templar, the military-religious order founded in Jerusalem around 1119 and dissolved under torture and political pressure by King Philip IV of France in 1307. The Templars occupied a unique cultural position: warrior-monks who had spent generations in the Holy Land, guardians of the pilgrimage routes, and custodians — according to persistent historical tradition — of some of the most significant religious artifacts in Christendom. Among the relics associated with them were fragments of the True Cross, reportedly captured and lost at the Battle of Hattin in 1187; the Holy Grail, whose connection to the Templars forms the backbone of an entire literary and speculative tradition; and even the severed head of John the Baptist, allegedly housed at their preceptory in Sidon.

Most intriguing for our purposes are the testimonies extracted during the Templar trials of 1307–1312, in which arrested knights — many under torture — described secret initiation rituals involving the veneration of a mysterious bearded head they called Baphomet. Several modern researchers, most notably historian Ian Wilson in his influential 1978 study, have proposed that this venerated head image was in fact the Shroud of Turin, folded so that only the facial portion was visible, and that the Templars were its custodians between its disappearance from Constantinople after the Fourth Crusade in 1204 and its reappearance in Lirey, France, in the 1350s. The Templar connection, in this theory, explains the Shroud’s mysterious provenance: Geoffrey de Charny, the French knight who first displayed the cloth at Lirey, shared his surname with Geoffroy de Charney, the last Templar Preceptor of Normandy, burned at the stake alongside Grand Master Jacques de Molay in 1314.

It is a compelling narrative, and it has found a wide readership. But it remains precisely that — a narrative, constructed from circumstantial connections and suppositional bridges rather than documented evidence. Confessions obtained under torture are among the least reliable categories of historical testimony. The Baphomet head described in the trial records bears no consistent description that unambiguously matches the Shroud image. The surname connection between Geoffrey de Charny of Lirey and Geoffroy de Charney of the Templars has never been genealogically established with certainty. And if the Templars possessed the Shroud for over a century, the silence of all other contemporary documentation about a cloth bearing the image of Christ remains entirely unexplained.

Catholic News Service: Knights secretly protected Shroud of Turin

A Vatican researcher has found evidence that the Knights Templar, the medieval crusading order, held secret custody of the Shroud of Turin during the 13th and 14th centuries.

The shroud, which bears the image of a man and is believed by many to have been the burial cloth of Jesus, was probably used in a secret Templar ritual to underline Christ’s humanity in the face of popular heresies of the time, the expert said.

The researcher, Barbara Frale, made the comments in an article published April 5 by the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano. The article anticipated evidence the author presents in an upcoming book on the Templars and the shroud.

Frale, who works in the Vatican Secret Archives, said documents that came to light during research on the 14th-century trial of the Templars contained a description of a Templar initiation ceremony.

The document recounts how a Templar leader, after guiding a young initiate into a hidden room, “showed him a long linen cloth that bore the impressed figure of a man, and ordered him to worship it, kissing the feet three times,” Frale said.

The idea that the Knights Templar were secret custodians of the shroud was put forward by British historian Ian Wilson in 1978. Frale said the account of the initiation ceremony, along with a number of other pieces of evidence, supports that theory.

What the Templar association does illuminate, however, is something important about the broader medieval relic culture in which the Shroud must be understood. The Templars — educated, widely traveled, deeply formed by proximity to the sacred geography of Jerusalem — were precisely the kind of men for whom the possession of holy relics carried enormous spiritual, psychological, and institutional significance. Whether or not they held the Shroud, they demonstrably revered relics, collected them, and integrated them into their devotional and ceremonial life. They were not unique in this. They were representative of a medieval Christian world in which the boundary between faith and physical object was porous, in which touching the sacred was considered a legitimate and powerful act of devotion, and in which the incentives — spiritual, political, and economic — for possessing holy artifacts were immense. It is within that world, not outside it, that the Shroud of Turin must ultimately be evaluated.

But Christian faith, rooted as it is in the authority of Scripture, cannot ultimately be governed by the desire for tangible confirmation. The apostle Paul declared that ‘we walk by faith, not by sight’ (2 Corinthians 5:7). The risen Christ himself told the doubting Thomas: ‘Because you have seen me, you have believed. Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed’ (John 20:29). The faith that honors God is not faith propped up by archaeological trophies — it is faith grounded in the Word of God, calibrated by the historical record, and sharpened by honest critical inquiry.

It is in that spirit — one of deep Christian commitment, rigorous historical methodology, and fidelity to the biblical text — that this essay examines the Shroud of Turin. My argument is straightforward: the Shroud of Turin, whatever its ultimate origin may be, cannot be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ. The biblical record itself rules it out. Furthermore, its documented history, its artistic and cultural context, and the scientific evidence surrounding it all converge on a single conclusion: the Shroud is a medieval artifact, almost certainly a deliberate human creation, and its veneration as a relic of Christ represents a devotional tradition untethered from the testimony of the New Testament authors who were actually present — or who interviewed those who were.

Part One: What the Bible Actually Says About the Burial Cloths

The Johannine Account: A Careful Eyewitness Record

Any serious examination of the Shroud of Turin must begin not with carbon dating or image analysis, but with the New Testament text itself. The Gospel of John — written by a man who, by his own testimony, was an eyewitness to the empty tomb — provides us with the most detailed account of what the disciples actually found when they arrived at the tomb on the morning of the first day of the week.

The critical passage is John 20:1-8. Mary Magdalene arrives at the tomb while it is still dark and finds the stone rolled away. She runs to tell Simon Peter and the Beloved Disciple — almost universally identified as John himself. The two men run to the tomb. The Beloved Disciple outruns Peter and arrives first. He stoops, peers in, and sees the linen cloths (Greek: ta othonia) lying there but does not enter. Then Peter arrives, characteristically impetuous, and goes straight into the tomb. What he sees is described with deliberate, almost meticulous precision:

‘He saw the linen cloths lying there, and the face-cloth, which had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen cloths but folded up in a place by itself.’ (John 20:6-7, ESV)

The Greek text here demands careful attention. The word rendered ‘linen cloths’ (othonia) is plural. The word rendered ‘face-cloth’ (soudarion) is singular and explicitly distinguished from the plural cloths. The text states unambiguously that these were separate objects, found in different locations within the tomb. The soudarion — the cloth that had covered Jesus’ head — was ‘folded up’ (Greek: entylisso) and placed ‘in a place by itself’ (Greek: eis hena topon), apart from the multiple body wrappings.

The Greek Vocabulary of First-Century Jewish Burial

First-century Greek burial terminology reflects actual burial practice, and John uses it with precision. The term othonia, the plural linen cloths or wrappings, corresponds to what we know from both literary and archaeological sources about Jewish burial customs of the Second Temple period. The body was prepared with spices — Nicodemus brought an enormous quantity of myrrh and aloes, approximately seventy-five Roman pounds, according to John 19:39 — and then wrapped with strips of linen. This wrapping was similar to, though not identical with, Egyptian mummification; the body was wound with multiple strips of linen, interspersed with the powdered spices.

The soudarion, the face-cloth or head cloth, was a separate piece. The term also appears in John 11:44, where Lazarus emerges from his tomb with his face bound with a soudarion that the bystanders are instructed to remove. In that same passage, Lazarus is described as bound with keiriai — grave cloths or bands — the same concept as the plural othonia. The consistent picture emerging from the Johannine vocabulary is one of multiple strips of linen binding the body, plus one separate cloth for the face.

The Synoptic accounts add a further detail. Luke 23:53 records that Joseph of Arimathea ‘wrapped’ Jesus’ body in a sindon — a single linen cloth — before placing him in the tomb. Mark 15:46 uses the identical term. This sindon was likely the preparatory cloth used for transport, not the final burial wrapping. By the time Nicodemus arrived with his enormous supply of spices and the body was properly prepared, the plural othonia of John 20 were in place. The sindon served a different function in the burial process — it was the cloth in which the body was transported from the cross to the tomb, not the final interment wrapping.

The Implications for the Shroud of Turin

Now hold the Shroud of Turin against this biblical picture and the contradiction becomes immediately, even dramatically, apparent. The Shroud is a single piece of linen — one cloth, fourteen feet long, designed to enfold the front and back of a body in a fold-over configuration. The claim of its proponents is that Jesus’ body was laid on the lower half of the cloth, then the upper half was folded back over the head and down the front of the body, resulting in the front and back images visible today.

But this is precisely not what John 20 describes. John describes multiple cloths (othonia, plural) wrapping the body, and one separate cloth for the head (soudarion) found in a different location. If the Shroud were authentic, we would expect to find John describing a single great linen cloth folded over the body. Instead, we find him describing what archaeologists and cultural historians recognize as standard first-century Jewish burial practice: multiple linen strips and a separate head cloth.

Some Shroud proponents have attempted to reconcile this discrepancy by arguing that the soudarion was a jaw-binding cloth placed under the chin and tied at the top of the head, and that John’s description is compatible with a single large cloth. But this tortured reading does violence to both the Greek text and to the archaeological and literary evidence for Jewish burial customs. The soudarion in John 11:44 covers Lazarus’ face entirely — Lazarus must have it removed before he can see. It is a face cloth, not a jaw band. And the plural othonia cannot grammatically or contextually be reduced to a single large sheet.

The biblical text, read honestly and in its first-century context, describes a burial configuration that is fundamentally incompatible with the Shroud of Turin. This alone should give pause to any Christian who takes the authority of the apostolic witness seriously. The eyewitness testimony of the Beloved Disciple — a man who bent down and looked into the actual tomb, a man who later wrote with the conviction of one who had seen and touched the risen Lord — describes burial cloths that do not match the relic venerated in Turin.

Part Two: The Documented History of the Shroud

The Suspicious Silence of Fourteen Centuries

If the Shroud of Turin is indeed the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, it is one of the most significant physical objects in human history. One would expect its existence to be attested in the historical record from the earliest possible period. The early church was not indifferent to the physical world; the resurrection of Jesus was, after all, a bodily resurrection, and the physical evidence of that resurrection mattered enormously to first-century Christians.

And yet the silence is deafening. For approximately fourteen hundred years after the death of Jesus, no historical document of any kind — no church father, no pilgrim’s account, no ecclesiastical inventory, no hagiography, no council proceeding — makes any unambiguous reference to a cloth bearing the image of Jesus’ crucified body. This is a silence that demands explanation.

The early church was extraordinarily interested in artifacts associated with the passion of Christ. By the fourth century, Helena, mother of the Emperor Constantine, had allegedly discovered the True Cross in Jerusalem. Pieces of the cross, the crown of thorns, the nails of the crucifixion, the sponge used to offer Jesus vinegar — all of these relics were known, discussed, venerated, and in some cases hotly disputed in patristic literature. Eusebius of Caesarea, Jerome, John Chrysostom, and Augustine of Hippo — these writers reference relics, travel to pilgrimage sites, and discuss physical artifacts associated with the life of Christ in some detail.

None of them mentions a cloth bearing the image of Jesus. None of the pilgrims who documented their journeys to Jerusalem in the fourth and fifth centuries — Egeria, the Bordeaux Pilgrim, Jerome’s companions — mentions such an astonishing object. The complete absence of any reference to an image-bearing burial cloth of Christ in fourteen hundred years of prolific Christian writing is a historical fact of the first importance, and it weighs heavily against the Shroud’s authenticity.

The First Certain Appearance: Lirey, France, 1354-1357

The first historically documented appearance of the Shroud of Turin is in Lirey, in the Champagne region of France, sometime between 1354 and 1357. A French knight named Geoffrey de Charny — not to be confused with the famous author of Le Livre de Chevalerie, though the two may have been related — apparently possessed the cloth and arranged for its display in the collegiate church he had founded at Lirey. Pilgrims flocked to see it, and souvenir badges depicting the cloth were produced — several of these have survived and are now among the most important pieces of evidence in the Shroud’s documented history.

The circumstances of the Shroud’s acquisition by Geoffrey de Charny are entirely unknown. He never explained how he came to possess it, and he died at the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 without having left any written record of its provenance. This acquisition by an unexplained route, at precisely the time when the cloth makes its first documented appearance in history, is itself historically suspicious.

The local bishop of Troyes, Henri de Poitiers, investigated the Shroud and concluded that it was a forgery — the work of a human artist. His successor, Pierre d’Arcis, wrote a memorandum to the Avignon pope in 1389 that is one of the most important historical documents in the Shroud controversy. In it, d’Arcis reported that his predecessor Henri de Poitiers had conducted an inquiry and ‘discovered the fraud and how said cloth had been cunningly painted, the truth being attested by the artist who had painted it, that is, made by human skill and not miraculously wrought or bestowed.’ The artist, d’Arcis reported, had confessed to making the cloth.

This is a remarkable document. Written in 1389, it asserts that a confession had been obtained from the artist who created the Shroud — that a named human being had admitted to fabricating the image. The document is not a rumor or speculation; it is an official communication from a bishop to a pope, written in the context of an ongoing ecclesial dispute about whether the cloth should be displayed and venerated.

The Shroud’s Journey to Turin

After the initial controversies at Lirey, the Shroud passed through several owners. Geoffrey de Charny’s granddaughter, Margaret de Charny, eventually sold or gave the cloth to the House of Savoy in 1453. The Savoys, who would later become the royal family of unified Italy, became its custodians. In 1578, the cloth was moved to Turin, where it has remained ever since. In 1983, the last Savoy heir, Umberto II, bequeathed it to the Holy See, and it is now technically the property of the Vatican, though it continues to be housed in Turin.

The pre-1354 history of the Shroud is the subject of enormous speculative literature. Proponents of its authenticity have proposed various theories: that it was the mysterious cloth called the Image of Edessa or the Mandylion, that it was preserved in Constantinople until the Fourth Crusade of 1204, and that it was in the possession of the Knights Templar. None of these theories is supported by unambiguous documentary evidence, and several involve significant historical gymnastics to connect dots that are simply not there.

The hard historical fact remains: we have no documented evidence for the Shroud’s existence before the mid-fourteenth century, and we have a contemporary bishop’s report that its creator had confessed to making it. These are not facts that responsible historical scholarship can set aside in favor of romantic speculation about crusading knights and Byzantine empresses.

Part Three: The Scientific Evidence

Radiocarbon Dating and Its Significance

In 1988, samples of the Shroud were subjected to radiocarbon (Carbon-14) dating by three independent laboratories: the University of Oxford, the University of Arizona, and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich. The laboratories worked independently and were unaware of each other’s results until all testing was complete. The three laboratories reached a remarkably consistent conclusion: the linen of the Shroud dated to approximately 1260-1390 CE, with a 95% confidence interval. The midpoint of this range falls almost precisely at the period of the Shroud’s first documented appearance in history.

This is a remarkable convergence of scientific and historical evidence. The radiocarbon dating places the linen’s origin in the medieval period, at precisely the time when the cloth appears for the first time in the historical record, and at roughly the time when Bishop d’Arcis’s unnamed artist was allegedly confessing to its creation.

Shroud proponents have raised objections to the radiocarbon dating, the most prominent being the ‘contamination hypothesis’ and the ‘invisible reweaving hypothesis.’ The contamination hypothesis argues that medieval repairs or biological contamination have skewed the dating results. The invisible reweaving hypothesis, advanced most notably by retired chemist Raymond Rogers, suggests that the samples taken in 1988 were taken from a corner that had been rewoven in the medieval period to repair fire damage, and thus do not represent the original cloth.

These hypotheses have been examined carefully by textile experts and scientists. The invisible reweaving hypothesis, in particular, has been found wanting by most textile scholars. Expert examination of the sampling area has not confirmed the presence of rewoven fibers consistent with medieval repair work. Moreover, contamination sufficient to shift a first-century date to a medieval date would require an extraordinary quantity of contaminant — more than would be visible to the naked eye and easily detectable by standard sample preparation procedures. The three independent laboratories used different pretreatment methods specifically to control for contamination, and they reached the same result.

Radiocarbon dating is not the only scientific evidence bearing on the Shroud’s authenticity. Pollen analysis conducted by Max Frei-Sulzer in the 1970s claimed to identify pollen from plants native to Palestine and Turkey on the cloth, suggesting it had spent time in the Middle East. However, Frei-Sulzer’s methodology has been questioned; his chain of custody for his samples was problematic, and he was later discovered to have been involved in the authentication of forged Hitler diaries. His pollen work on the Shroud must be treated with considerable caution.

The Image Itself: What Science Tells Us

Perhaps the most astonishing feature of the Shroud is the image itself. It is not painted in any conventional sense; it has a three-dimensional quality that can be analyzed mathematically, and it lacks the brushstrokes or medium deposits that would be expected from conventional painting techniques. This has led some researchers to propose that the image was formed by some extraordinary mechanism — the burst of radiation at the moment of resurrection, a hypothetical ‘flash photolysis’ process, or some other phenomenon beyond our current understanding.

The image’s unusual properties are real, and they deserve acknowledgment. The Shroud image is not a simple medieval painting, and simplistic dismissals of it as such miss the genuine complexity of the object. However, the unusual properties of the image do not require a supernatural explanation. Researchers have demonstrated that various medieval techniques — including proto-photographic processes, corona discharge effects, and sophisticated application of iron oxide-containing pigments — can produce images with properties similar to those observed on the Shroud.

Luigi Garlaschelli, an Italian chemist, demonstrated in 2009 that rubbing iron oxide pigment over a linen cloth placed on a real human body and then subjecting the cloth to aging processes could produce an image with characteristics closely resembling the Shroud image. Joe Nickell, a forensic investigator and longtime Shroud researcher, has similarly demonstrated the feasibility of various medieval image-formation techniques. The point is not that any particular technique has been proven to be the method used — it is that the image’s properties do not require us to invoke miraculous or scientifically unprecedented processes.

The bloodstains on the Shroud deserve particular attention, and none more so than the lance wound in the side. John 19:34 records that a Roman soldier — identified in later tradition as Longinus — pierced the already-dead Jesus with a spear, producing an outflow of “blood and water,” a detail John emphasizes with unusual solemnity as eyewitness testimony. Medically, this outflow is most plausibly explained as blood from a cardiac vessel combined with pericardial or pleural fluid. Forensically, this wound presents a specific challenge to the Shroud’s authenticity: the lance was thrust while Jesus hung upright on the cross, after death. The resulting blood flow would have followed gravity downward along a vertical body, then changed character and direction as the body was taken down, carried horizontally, and laid in a tomb. A genuine burial cloth would be expected to record that complex, multi-positional flow history in its stain patterns — not a single, directionally simple deposit.

More broadly, proponents argue that the Shroud’s bloodstains are anatomically correct and consistent with Roman crucifixion, including nail wounds in the wrists rather than the palms. However, forensic examination has raised significant questions. Matteo Borrini and Luigi Garlaschelli, publishing in the Journal of Forensic Sciences in 2019, argued that the bloodstain patterns on the Shroud are more consistent with blood applied to the cloth on a standing or moving figure than with blood naturally flowing from wounds onto a supine burial cloth. Blood flowing from a crucified and then horizontal body under the influence of gravity would produce patterns distinctly different from what the Shroud displays. And the “water” component John specifically records in the lance wound — theologically significant enough that he treats it as a keystone of his eyewitness testimony — leaves no apparent trace in the Shroud’s side stain, an omission that proponents have never satisfactorily explained. Finally, it bears noting that any sophisticated medieval craftsman constructing a devotional image would have had intimate familiarity with the passion narratives. Creating wound placements consistent with the Gospels required no miraculous knowledge — only a thorough reading of John.

The Anatomical and Artistic Context

When the Shroud image is placed in its art-historical context, further questions arise. The image of the man on the Shroud conforms remarkably well to the conventions of medieval northern European religious art in its depiction of Christ’s passion. The flowing hair parted in the middle, the beard, the proportions of the face and body — all of these conform to the iconographic conventions that developed in Byzantine and medieval Western art.

This is historically significant because we have no reliable information about what Jesus of Nazareth actually looked like. The earliest Christian art — catacomb paintings and sarcophagus reliefs from the second and third centuries — typically depicted Jesus as a clean-shaven young man in the Roman style. The long-haired, bearded image of Christ that dominates later Christian art was a later development, heavily influenced by the conventions of depicting Zeus and other divine figures in Greco-Roman art. If the Shroud image truly dates from the first century, it is remarkable that its depiction of Jesus conforms not to early Christian artistic conventions but to the later conventions that emerged precisely in the Byzantine and medieval periods, when, coincidentally, the cloth first appears in the historical record.

Part Four: Theological and Ecclesial Considerations

What the Church Has Actually Said

It is important to be precise about the official position of the Roman Catholic Church on the Shroud of Turin. The Church has never formally declared the Shroud to be authentic. It has never been the subject of an ex cathedra papal statement, and no ecumenical council has pronounced on its authenticity. The Church’s position has been carefully calibrated to avoid both an official endorsement of authenticity and an official declaration that it is a forgery.

Pope John Paul II, who was deeply personally devoted to the Shroud, visited it in 1998 and called it ‘a mirror of the Gospel.’ But he carefully avoided making any claim about its physical authenticity, framing his reflection in terms of what the image evokes spiritually rather than what it proves historically. Pope Francis has similarly avoided authoritative statements about the cloth’s origins while speaking of it in devotional terms.

The Church’s cautious official position is, in its way, a tacit acknowledgment that the evidence for the Shroud’s authenticity is insufficient to sustain a formal dogmatic statement. This matters for Protestant and evangelical Christians approaching the question: the Shroud has not been officially declared authentic, even by the institution that houses it and benefits most from pilgrim traffic to view it.

There is something worth pausing over in this institutional posture, because Protestant and evangelical Christians engaged in conversations with members of the Latter-day Saint tradition will recognize it immediately. It is the same epistemological maneuver that LDS leadership employs when confronted with the historical and archaeological problems surrounding Book of Mormon geography, the multiple First Vision accounts, or Joseph Smith’s anachronistic translation of the Kinderhook Plates. In both cases, the institution speaks with devotional warmth about claims that cannot survive historical scrutiny, carefully avoiding the kind of specific, falsifiable affirmations that would expose those claims to direct refutation. In both cases, the institution captures the devotional benefit of popular belief while assuming none of the evidential liability of defending it. And in both cases, when pressed, the retreat is always to the same ground: some things must be received by faith. This is not a sufficient answer — not for the Shroud, and not for the truth claims of the Restoration. Faith that cannot survive an honest examination of the evidence on which it rests is not biblical faith. It is institutional self-protection dressed in the language of piety.

The Relic Industry and Its Dangers

To understand the Shroud of Turin in its proper historical context, we must understand the medieval relic industry — not as a colorful footnote to church history, but as one of the dominant economic, political, and theological forces shaping Western Christendom from roughly the fourth century through the Reformation. The veneration of relics was not a peripheral or eccentric practice confined to the uneducated poor. It was central to popular piety at every level of medieval society, embraced by peasants and popes alike, encoded in canon law, celebrated in the liturgical calendar, and woven into the architectural ambitions, the pilgrimage economies, and the political rivalries of medieval Europe. To encounter the Shroud without understanding this world is to encounter it in a vacuum — and a vacuum is precisely the environment in which implausible claims flourish most comfortably.

The Theology Behind the Trade

The theological foundation for relic veneration was laid early. As Christianity spread through the Roman Empire and the cult of the martyrs developed, the physical remains of those who had died for the faith were accorded special honor. The logic was not without internal coherence: if the body is the temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Corinthians 6:19), and if the resurrection promises the transformation and glorification of the physical body, then the bodies of the saints possess a dignity that survives death. The Council of Nicaea II in 787 formally endorsed the veneration of relics, and by the early medieval period, the practice had acquired theological, legal, and ceremonial weight that made it virtually unassailable within the institutional church.

Three categories of relics were formally distinguished in medieval theology. First-class relics were the physical remains of saints — bones, flesh, hair, teeth. Second-class relics were objects that had been in contact with a saint during life — clothing, personal items, instruments of their work, or martyrdom. Third-class relics were objects that had been touched to first or second-class relics, thereby acquiring a derivative sanctity. This taxonomy, developed with genuine theological seriousness by figures including Thomas Aquinas, created a framework within which almost any physical object could be brought into the sacred economy. The system was, in retrospect, an invitation to fraud so open and so lucrative that it is remarkable the abuses took as long to develop as they did — though in truth they did not take long at all.

The Economics of the Sacred

The economic dimensions of the relic trade were enormous and are essential to understanding how the market for holy objects functioned. A church or monastery that possessed a significant relic became a pilgrimage destination. Pilgrimage destinations generated foot traffic. Foot traffic generated revenue from the offerings pilgrims deposited at shrines, from the hospitality industry that grew up around major pilgrimage sites, from the sale of souvenir badges, ampullae filled with holy water or oil, and miniature replicas of the relics themselves, and from the general commercial activity that accompanied any large gathering of people. Santiago de Compostela, Canterbury, Rome, and Jerusalem were not merely spiritual destinations; they were economic engines of medieval Europe, and their prosperity rested substantially on the relics they housed.

The competition between religious institutions for significant relics was fierce, and it generated behavior that ranged from the merely undignified to the frankly criminal. The practice of furta sacra — holy theft — was not merely tolerated but in some cases celebrated. When the monks of Conques stole the relics of Saint Foy from the church at Agen in 866, the theft was later described in hagiographical literature as divinely orchestrated, the saint herself having chosen her new home. The relics of Saint Mark were smuggled out of Alexandria by Venetian merchants in 828, reportedly concealed under layers of pork and cabbage to discourage inspection by Muslim customs officials — and their arrival in Venice was treated as a triumph, the justification for building one of the most magnificent churches in Christendom. The bones of the Three Magi, brought to Cologne in the twelfth century, transformed that city into a major pilgrimage site virtually overnight. Relics were, in the most literal sense, portable wealth — and they were treated accordingly.

Noble families competed for them with the same intensity they brought to territorial disputes. Possession of a significant relic enhanced the spiritual prestige of a dynasty, attracted patronage and pilgrimage to family-endowed churches and monasteries, and demonstrated divine favor in ways that carried genuine political weight. When Louis IX of France purchased the Crown of Thorns from the Latin Emperor of Constantinople in 1239 — paying an extraordinary sum, reportedly more than the annual revenues of several French provinces — he was making not merely a devotional gesture but a statement of royal and spiritual supremacy. The Sainte-Chapelle, built in Paris specifically to house the Crown of Thorns, was not a chapel in any modest sense; it was a theological and political manifesto in stained glass and stone, proclaiming France as the new Israel and its king as the most Christian monarch in Christendom.

The Scale of the Absurdities

The incentives for producing and promoting relics were so enormous, and the mechanisms for verifying authenticity so primitive, that the medieval period witnessed the creation of an almost unimaginable quantity of purportedly holy objects. No central registry existed. No systematic authentication process operated. Local bishops might investigate particularly suspicious claims — as indeed happened with the Shroud at Lirey — but their rulings carried no universal authority, and a relic condemned in one diocese might be venerated without interference in the next.

The results were, by any sober accounting, farcical — though the comedy carries a dark edge when one considers how many sincere believers were defrauded of money, trust, and theological clarity. John Calvin, in his 1543 Treatise on Relics — one of the most devastating pieces of institutional criticism produced by the Reformation — catalogued the absurdities with the controlled fury of a man who had spent years watching the faithful exploited. He noted that the fragments of the True Cross distributed across European churches were, in aggregate, sufficient to fill a large ship — a point he made with only slight exaggeration, since a later calculation by the humanist scholar Erasmus reached a similar conclusion. Calvin documented multiple heads of John the Baptist venerated in different locations simultaneously — Amiens, San Silvestro in Rome, and others — without any apparent institutional embarrassment about the biological implausibility of a man possessing multiple heads. He catalogued multiple complete bodies of the same apostles spread across different churches, each claiming to hold the authentic remains. He noted that the milk of the Virgin Mary was venerated in enough separate locations to have nursed an army, that her wedding ring was displayed in at least four different cities, and that the swaddling clothes of the infant Jesus appeared to be so numerous as to suggest a remarkably prolific production.

Most strikingly — and most relevant to the Shroud — Calvin observed that several churches claimed to possess the burial cloths of Jesus. He wrote with barely restrained astonishment that multiple linens were venerated as the authentic grave clothes of Christ, none of which could be reconciled with the others or with the Gospel accounts. The Shroud venerated at Lirey, and later Turi,n was not, in other words, competing in an empty market. It was entering a field already crowded with similar claims, a field in which the primary qualification for acceptance was not historical verifiability but devotional utility.

The Holy Prepuce — the foreskin of Jesus, allegedly preserved from his circumcision — deserves particular mention, not because it is pleasant to discuss but because its history illuminates with unusual clarity the dynamics of the medieval relic trade. At various points in the medieval period, at least eight separate churches claimed to possess the authentic foreskin of Christ, each with its own provenance narrative, its own miracles attributed to the relic’s intercession, and its own pilgrimage economy. The Feast of the Holy Circumcision, celebrated on January 1st, became in some communities an occasion for venerating these relics. The theological awkwardness of the claim — that a portion of the physical body of the incarnate Son of God had been detached, preserved, and was now available for pilgrims to venerate in a small Italian hill town — was apparently not sufficient to prompt institutional skepticism. The pilgrims came. The offerings were deposited. The economy of the sacred continued to function.

The Specific Context of Fourteenth-Century France

Against this backdrop, the appearance of a burial cloth of Jesus in mid-fourteenth-century France is not historically surprising. It is, in fact, entirely predictable — and the specific circumstances surrounding it are almost a textbook illustration of how the relic market operated.

The mid-fourteenth century was, paradoxically, both a period of enormous disruption and a period of intensified religious anxiety. The Black Death had swept through Europe between 1347 and 1351, killing perhaps a third of the continent’s population in some regions. The Hundred Years’ War between France and England had begun in 1337 and would grind on for over a century. Social dislocation, economic stress, and the raw terror of mass death created precisely the psychological conditions in which the tangible comfort of sacred objects becomes most compelling. People who had watched their neighbors, their children, and their priests die by the thousands in a matter of months were not in a skeptical frame of mind when a cloth bearing the image of the suffering and buried Christ was presented for their veneration. They were desperate for contact with the sacred, hungry for evidence that the God of the resurrection had not abandoned his creation.

What would be surprising — genuinely, historically surprising — given everything we know about the economics of medieval pilgrimage, the incentives for relic production, the climate of religious anxiety in mid-fourteenth-century France, and the demonstrated capacity of medieval craftsmen to produce sophisticated devotional objects, is if someone had not produced such a cloth. The Shroud of Turin did not appear in a vacuum. It appeared in a world that had been producing, promoting, disputing, stealing, selling, and venerating relics for a thousand years. It arrived precisely when demand was highest, precisely where economic and political incentives aligned, and precisely in the manner — without documented provenance, promoted by a noble family, attracting pilgrims and offerings — that characterized the entire industry. Understanding this does not resolve every question about the cloth’s origin. But it does establish, with considerable force, that the burden of proof runs firmly against authenticity — and that the historical context offers no shortage of plausible explanations for how such an object came to exist.

The Authority of Scripture Over Tradition and Relic

From a Reformed and evangelical Protestant perspective, the Shroud of Turin raises not merely historical and scientific questions but a fundamental theological one: what is the basis of Christian faith? The Protestant Reformation, following the lead of Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli, was rooted in the principle of sola scriptura — Scripture alone as the final authority for Christian belief and practice. The veneration of relics was, for the Reformers, not merely a minor pastoral problem but a symptom of a deep theological confusion: the substitution of human traditions and physical objects for the Word of God as the foundation of faith.

The Shroud of Turin, whatever one makes of its physical properties, represents precisely this kind of substitution when it is presented as evidence for or confirmation of Christian faith. The resurrection of Jesus Christ is attested by the apostolic witness of the New Testament — by eyewitness testimony, by the transformation of the disciples from frightened fugitives to martyrs willing to die for their proclamation, by the conversion of Paul on the Damascus road, and by the theological coherence of the New Testament’s resurrection proclamation. This testimony is the foundation of Christian faith.

No relic can add to or confirm that testimony in any theologically meaningful sense. If the Shroud were proven beyond all reasonable doubt to be a first-century linen cloth bearing the image of a crucified man, it would still not prove the resurrection of Jesus. At most, it would prove that a man was crucified and buried in a particular manner. The resurrection — the transformation of the physical body of Jesus into the glorious body of the risen Lord — is precisely the event that left no physical trace in the ordinary sense, because it involved not the preservation of the physical but its transformation into something new and eschatological.

And if the Shroud is not authentic — as the evidence strongly suggests — then presenting it as confirmation of Christian faith is actively harmful to the cause of the Gospel. It invites the response: ‘Your faith rests on a medieval forgery.’ The Christian who has been encouraged to find assurance in the Shroud’s ‘authenticity’ is building their house on sand. When the sand shifts — and the historical and scientific evidence that it is a forgery is substantial — the house falls.

Part Five: Reading the Evidence Honestly

The Convergence of the Evidence

Let us now stand back and survey the terrain of the evidence as a whole. We have five distinct lines of evidence, all pointing in the same direction:

First, the biblical record. The eyewitness testimony of John 20 describes burial cloths (plural) binding the body and a separate head cloth, a description fundamentally incompatible with the configuration of a single large linen cloth folded over the body. The New Testament never mentions a cloth bearing the image of Jesus. The earliest Christian witnesses, who had the greatest possible motive to identify and preserve such an object if it existed, give us no indication that any such cloth was known to them.

Second, the historical record. Fourteen hundred years of Christian writing — patristic literature, pilgrimage accounts, ecclesiastical inventories, hagiographies, council proceedings — contain no unambiguous reference to a burial cloth bearing the image of Christ. The cloth appears without explanation in mid-fourteenth-century France in the possession of a knight who never explained how he acquired it, at a time when the relic trade was at its commercial and cultural height. The local bishop reported that an artist had confessed to the fabrication.

Third, the scientific evidence. Three independent radiocarbon dating laboratories, using different pretreatment methods, dated the linen to the period 1260-1390 CE, precisely the period of the cloth’s first documented appearance. The objections raised against this dating have not been substantiated to the satisfaction of the scientific community.

Fourth, the image analysis. While the image has genuinely unusual properties that are not easily explained by standard medieval painting techniques, it is consistent with various medieval image-formation processes that have been demonstrated by researchers. It conforms to the iconographic conventions of medieval Western art rather than to early Christian artistic traditions. Its unusual properties do not require a supernatural explanation.

Fifth, the theological and ecclesial context. The Shroud has never been officially declared authentic by the Roman Catholic Church, despite strong devotional attachment to it. The history of medieval relic production provides ample context for understanding how such an object could have been created and promoted. The entire enterprise of finding confirmation for Christian faith in physical relics represents a theologically problematic substitution of material objects for the testimony of Scripture.

Five independent lines of evidence all pointing in the same direction are, in historical methodology, about as compelling a convergence as one typically encounters. The honest historian — the historian who applies the same standards of evidence to this question that would be applied to any other question of medieval provenance — reaches a conclusion that is difficult to escape: the Shroud of Turin is a medieval artifact of human origin, not the burial cloth of Jesus Christ.

A Note on Motivated Reasoning

The Shroud of Turin has generated an unusual sociology of inquiry. On the one side are committed believers whose faith in the Shroud’s authenticity leads them to propose increasingly elaborate theories to explain away contrary evidence — theories of invisible reweaving, exotic contamination, Byzantine origin, Templar custody — none of which is supported by the kind of evidence that would normally be required in historical research. On the other side are committed skeptics who sometimes dismiss genuine puzzles about the cloth’s image properties without adequate engagement.

The historian’s task is to resist the pull of both camps and follow the evidence where it leads. The evidence leads to a medieval origin. The evidence also tells us that the Shroud is a genuinely complex object, not a simple painted forgery, and that the mechanism by which its image was formed is not fully understood. These two conclusions are not in tension: a medieval object can have unusual properties that we do not fully understand while still being a medieval object.

What the evidence does not support is the conclusion that the Shroud is the authentic burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth. That conclusion requires us to ignore the testimony of John 20, to dismiss fourteen hundred years of silence, to set aside the converging conclusions of three independent scientific laboratories, to disregard the confession reportedly obtained by Bishop Henri de Poitiers, and to explain away the cloth’s conformity to medieval artistic conventions. This is too high a price to pay for a relic.

Conclusion: Faith Without Trophies

The Christian faith does not need the Shroud of Turin. It has never needed it. For the first fourteen centuries of Christian history, believers proclaimed the resurrection of Jesus, built the church, suffered martyrdom, produced the greatest flowering of art, music, philosophy, and architecture in Western history, and transformed the moral imagination of the world — all without a single reference to a burial cloth bearing the image of their Lord.

What the Christian faith has always rested on is the testimony of the apostles. That testimony is preserved in the New Testament documents — documents written by eyewitnesses or close associates of eyewitnesses, documents that have survived the scrutiny of two thousand years of critical scholarship, documents whose historical core — the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus — has been attested by non-Christian sources from Josephus to Tacitus. The resurrection appearances described in 1 Corinthians 15 — a document written within twenty years of the crucifixion, citing traditions that Paul received within years of the event — represent historical evidence of a quality that the Shroud of Turin cannot approach.

The Shroud of Turin, venerated by millions and surrounded by an extraordinary cottage industry of books, documentaries, conferences, and websites, ultimately offers false comfort. It says: ‘See, here is the cloth that wrapped him. Here is the image that proves he was buried and rose.’ But the disciples who first proclaimed the resurrection had no such cloth to show. Peter stood up on the day of Pentecost and proclaimed: ‘This Jesus God raised up, and of that we all are witnesses’ (Acts 2:32). Not: ‘We have his burial cloth as evidence.’ The evidence was the witnesses — the living men and women who had seen the risen Lord with their own eyes.

The honest examination of the Shroud of Turin leads to the conclusion that it is a medieval artifact, probably created in fourteenth-century France, certainly incompatible with the description of Jesus’ actual burial cloths given by the apostle John, and bearing no legitimate claim to serve as a confirmation of Christian faith. Its continued veneration is a pastoral and theological problem for the communities that promote it, and its continued presentation as evidence for the resurrection is an apologetic liability rather than an asset.

For those who have built their faith partly on the Shroud’s claimed authenticity, this conclusion need not be threatening. The resurrection of Jesus Christ rests on ground far more solid than any physical relic. It rests on the testimony of men and women who died for that testimony, on the transformation of the community that proclaimed it, on the coherence and power of the Gospel narrative, and ultimately on the living witness of the Holy Spirit who confirms to the believer the truth of what the apostles proclaimed. That is a foundation that no radiocarbon date can undermine, because it is not a foundation made of linen.

The way of faith, as the author of Hebrews declares, is ‘the conviction of things not seen’ (Hebrews 11:1). The resurrection of Jesus is the great unseen event at the heart of Christian proclamation — unseen by us, but witnessed by those who saw the risen Lord and could not keep silent about what they had seen. We honor their witness best not by reaching for physical trophies to confirm what they proclaimed, but by trusting the testimony they gave us and living in the light of the resurrection they announced.

The Shroud of Turin, whatever its ultimate origin, cannot give us that. Only the Word of God can.

— END —

Excellent article!

Very detailed and very interesting!